Strength Training Manual: Agile Periodization and Philosophy of Training

1. Introduction

2. Agile Periodization and Philosophy of Training

3. Exercises – Part 1 | Part 2

4. Prescription – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

5. Planning – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

I am very happy to announce that I am finishing the Strength Training Manual. I decided to publish chapters here on Complementary Training as blog posts for two reasons. First, I want to give members early access to the material. And second, this way I can gain feedback and correct it if needed before publishing it.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Enjoy reading!

Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision-making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning (Jovanovic, 2018). Contemporary planning strategies are based on predictive responses and linear reductionist analysis, which is ill-suited for dealing with uncertain and complex domains, such as human adaptation and performance (Kiely, 2009, 2010a,b, 2011, 2012, 2018; Loturco & Nakamura, 2016). The word agile comes from the IT domain, where they figured out that the industrial-age approach to project management (i.e., waterfall) doesn’t work very well in the highly changing and unpredictable environment of the software industry and markets (Rubin, 2012; Stellman & Greene, 2014; Sutherland, 2014; Layton & Ostermiller, 2017; Layton & Morrow, 2018).

I will introduce a few aspects of the Agile Periodization, but explaining the whole Agile Periodization framework is beyond this manual, so I direct interested readers to my other book (Jovanovic, 2018) for a better and more complete overview.

Iterative Planning

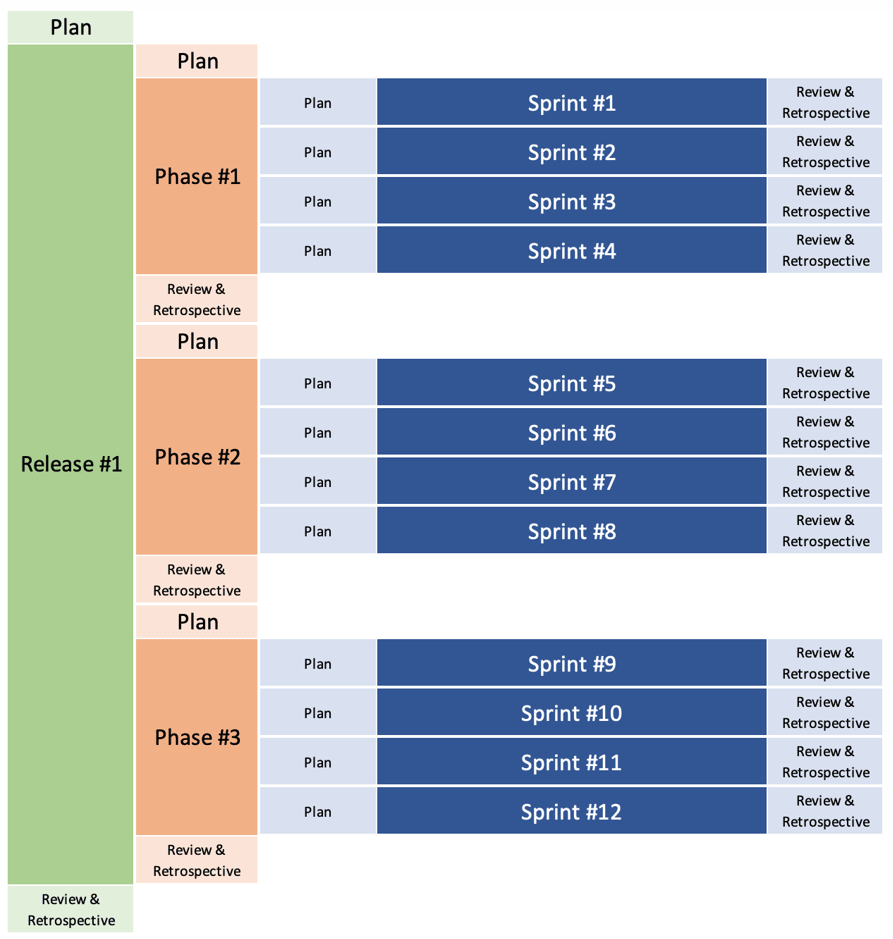

Iterative planning consists of iterative processes of (1) planning, (2) development, and (3) review and retrospective. These can be applied on different time scales, and here I selected three as well: (1) release, (2) phase, and (3) sprint (see Figure 2.1). Sprint can be considered one microcycle, the phase can be considered mesocycle, and the release can be regarded as one macrocycle, for those familiar with more contemporary periodization terms ((Bompa & Buzzichelli, 2015, 2019).

Figure 2.1 Iterative Planning. Consisting of three time-frames: release, phase and sprint, each having a planning component, development component, and review & retrospective component (which are needed to update the knowledge for the next iteration)

Why did I choose different names? To act smart? First of all, different frameworks demand different languages. Second of all, planning in this framework, as opposed to contemporary planning strategies, is iterative rather than detailed up-front. Taking all of that into account, it is essential to use the terminology which will better represent the iterative planning approach and differentiate it from more common planning strategies as well.

Top-down vs. Bottom-Up

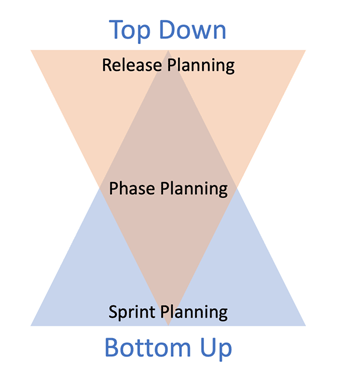

These three time-frames are needed to implement both top-down and bottom-up planning, which I consider to be complementary (Kelso & Engstrøm, 2008), rather than dichotomous (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Top-Down and Bottom-Up planning as a complementary pair.

Top-down refers to seeing the big picture, deciding about goals and objectives and strategies about reaching those, and answering the questions “What should be done and why”. This is a quite common approach in contemporary periodization, where one starts with the big picture and goes into designing the smallest training sessions. Agile Periodization release planning is mostly concerned with seeing the big picture and making sure that other phases are aligned and constrained with the objectives.

Bottom-Up refers to starting with “what can be done now and how”. Bottom-up begins with the problems at hand (e.g., equipment and facilities, level of athletes, and so forth), rather than with a vision (which is the goal of the top-down approach). Sprint planning is mostly concerned with figuring out what can be done and how (within constraints of the bigger picture established with release and phase plan). To utilize bottom-up approach, one needs to embrace the concept of MVP, or minimum-viable program 1, which is the least complicated training program that serves one as a vehicle, while one discovers what can and should be done and how.

An essential concept of MVP is that all qualities identified as important (from the lowest resolution, or from a functional significance perspective) are being addressed. For example, making sure there is some speed/sprint work, quality strides, jumps, lifts (major movement patterns being addressed) trumps worrying about chest flies, rear deltoideus work, or whether Nordic curls are better than RDLs. MVP is the epitome of precision vs. significance conundrum (see Figure 1.1).

It is a myth, that when someone starts working with a team, they will immediately know the objectives and what should be done (top-down approach) to improve performance. That is bullshit. You need to figure out what you are dealing with first, figuring out the problems before deciding about vision and long-term phases. Here is the example: imagine starting to work with a soccer team and approaching planning from these two perspectives:

Bottom-Up: I have 3 dumbbells, athletes who never lifted in their life, and a head coach who doesn’t believe in physical preparation for soccer. What am I supposed to do to get the MVP, build the trust with athletes, coaches, and board, and go from there?

I am not saying that the top-down approach is not important, but since it has been overemphasized in the contemporary planning and periodization literature, while still missing to address issues from where the rubber meets the road, I believe that what we need to do is to emphasize bottom-up approach more, to reach some type of balance in the planning universe (pun intended). I also believe that both are important and complementary, because if the only type of planning you do is bottom-up, how you are going to judge the results without the bigger picture, objectives, and vision. This is the reason why both top-down and bottom-up approaches are implemented in Agile Periodization using three components: release, phase, and sprint (see Figure 2.2).

Within each of these components (release, phase, sprint), there are three distinctive and formal parts: (1) plan, (2) development, and (3) review and retrospective. Of the three, one of the most neglected, but most important is review and retrospective. Let’s apply this to strength training.

Phases of Strength Training Planning

Strength training planning can be seen as consisting of three iterative components:

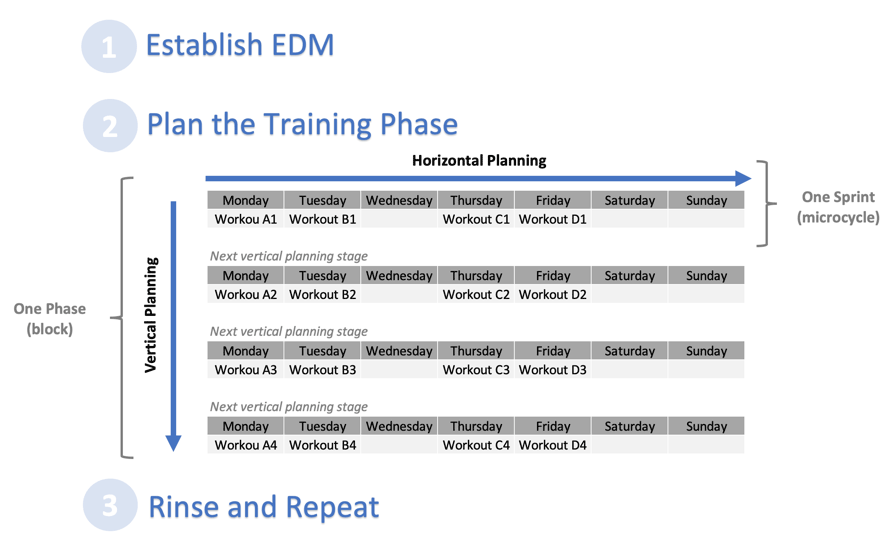

- Establish EDM (every-day maximum)

- Plan the training phase

- Rinse and repeat

Each of these phases will be covered in more detail in the following chapters (Chapters 4-6), but it is essential to see how they correspond to the iterative nature of sprint and phase components of the Agile Periodization (see Figure 2.3)

Figure 2.3 Three iterative components of strength training planning.

In my view, these three components are building blocks of the bottom-up approach, and this whole manual revolves around these three. I do believe that these shorter iterative programs are needed to course correct and adapt to the newly discovered observations and insights (see Bayesian updating in the previous chapter) compared to longer top-down phases.

Qualities, Methods, and Objectives

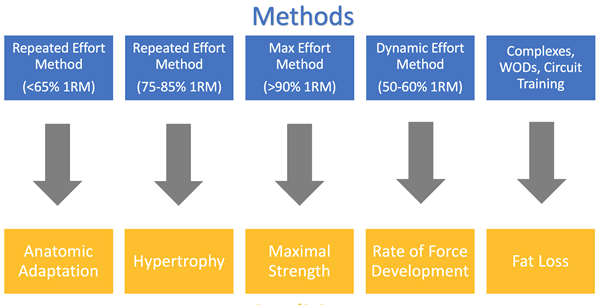

Coaches (luckily not all of them) often use the following mental model (Small World; see previous chapter) that is dominated by physiology and biomechanics reductionist approach (Figure 2.4):

Figure 2.4. An overly simplistic causal model of methods and qualities

Since physiology and biomechanics define the place of things, we also automatically assume that we know what to do with it (the forum for action). However, there are a few issues with this. Firstly, the number of qualities identified is usually related to some physiological model of performance (for example in endurance we have VO2max, Lactate Threshold, and Economy as main qualities), or latent variables or constructs 2. Secondly, we immediately assume that once we identify those qualities, there are training methods that can directly hit those qualities (sometimes we also refer to “training zones” or “zones of intensity”).

Unfortunately, this is a flawed model. The more realistic model is the following (see Figure 2.5)

Figure 2.5 More realistic model, where there is no clear cut between Qualities and Methods

As mentioned in the previous chapter, rather than relying solely on physiology and biomechanics to define what there is (although, I am by no means underestimating the importance of knowing these disciplines and analytical approaches) and what should we do with/about it, I want to take a more phenomenological (and pragmatic) approach in this manual.

How does this relate to strength training? We tend to define objectives and methods of strength training using the analytical approach of biomechanics and physiology 3:

- Maximal and Relative Strength

- The goal is the development of maximal strength

- The method used for developing this motor quality is Maximal Effort, or ME

- Explosive Strength

- The goal is the development of explosive strength, or the ability to produce great force in the least amount of time

- The method used for developing this motor quality is Dynamic Effort or DE

- Muscular Hypertrophy

- The goal is the development of muscular hypertrophy, without going into the debate of sarcoplasmic vs. myofibrillar hypertrophy

- The method used for developing this motor quality is Submaximal Effort, or SE (mostly for functional or myofibrillar hypertrophy) and Repetition Effort, or RE (primarily for total or sarcoplasmic hypertrophy)

- Muscular Endurance

- The goal is the development of muscular endurance, fat loss, anatomic adaptation and sarcoplasmic hypertrophy (depending on the context). Some also put ’vascularization’, ’glycogen depletion’, ’mitochondria development’ as the goal of this method

- The method used for developing this motor quality is Repetition Effort or RE

So we believe, that for example, if one wants to improve max strength, one needs to use >85-90% 1RM loads. But then we have athletes coached by Boris Sheiko who usually lift lower than 80% 1RM weights and are some of the strongest in the world. So, these categories create paradoxes because they make us falsely confident in the involved processes leading to a specific goal, but unfortunately, we are dealing with complex systems and uncertainties.

So what is the solution? In my opinion, the answer is using complementary phenomenological objectives. The phenomenological approach defines qualities as they manifest themselves in our experience or performance (Loland, 1992; Jovanovic, 2018). For example, a powerlifter in the competition struggles to lift his opener (first weight), and that sets him up poorly for the other tries. From the analytical (i.e., biomechanical and physiological) standpoint, one can dissect this to rate of force development, fast-twitch synchronization, or whatever I-want-to-sound-smart constructs. But from the phenomenological perspective, one struggled to find the right mindset and use the suit in the right way. Defining qualities like this gives more meaning and create affordances 4 for action (something that is lacking in analytical approach – see Is/Ought problem later).

Another example might be an endurance runner (not the best example in Strength Training manual right, but bear with me for a second 5) . This endurance runner’s result in the 1500m competition is 3 minutes and 56 seconds. His VO2max is 68 ml/kg/min. And how the hell does this helps in figuring out the forum for action? What should he do to improve? Phenomenologically, we might notice that he lost the pace in the last lap by losing his rhythm. And this gives us more affordances for action – in other words, the forum for action. The coach can make better prescriptions based on the phenomenological analysis. So, rather than prescribing VO2max intervals (that sounds ‘scientific’ and ‘objective’), she might make this athlete focus on his speed and pace after a long run. Could he be a high-level 1500m without high VO2max? Or without elastic force-generating ability? Hell no! To put this in philosophical terms, high VO2max is a necessary condition to be a high-level 1500m runner, but it is not sufficient. Thus, one cannot make simplistic causal reasoning that one needs to perform VO2max intervals (e.g., 4x3min @105% MAS or vVO2max), to improve VO2max, which will improve 1500m performance. The causal network is very complex and unpredictable, which doesn’t mean understanding physiology is unnecessary, but understanding it is not sufficient when it comes to enhancing athletes’ performance.

Similar problems are experienced in other domains, for example, psychometry, with the concepts of IQ, g-factor, and Big Five factors of personality (Borkenau & Ostendorf, 1998; Molenaar, Huizenga & Nesselroade, 2003; Borsboom, Mellenbergh & van Heerden, 2003; Molenaar, 2004; Hamaker, Dolan & Molenaar, 2005; Borsboom, 2008; Molenaar & Campbell, 2009; Cramer et al., 2012; Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Schmittmann et al., 2013; Bringmann et al., 2013; Maul, 2013; Nesselroade & Molenaar, 2016; Borsboom et al., 2016; Guyon, Falissard & Kop, 2017; Kovacs & Conway, 2019). If you are interested in this topic, I suggest you check the provided references. The key takeaway is that causation is not as simple as Figure 2.4.

When it comes to strength training, using an analytical perspective, strength qualities are (1) maximal strength, (2) explosive strength, (3) strength endurance, and (4) hypertrophy. The question is how do they differ and manifest themselves in powerlifter versus soccer player? How do they differentiate into finer qualities? In my opinion, the scientific-analytical approach needs to be complemented (sometimes even replaced, or started at least) with a phenomenological analysis of the qualities and methods. We do need to understand that we are dealing with uncertainty and complexity, and a pluralistic approach of using multiple Small World models is needed, rather than ideological belief in only one model (Mitchell, 2002, 2012; Page, 2018). This means that all pre-planning serves only as a prior (see the previous chapter on Bayesian updating) which needs to be updated and experimented with, using the iterative approach of Agile Periodization. Following the long-term periodization phases of the Russians gives us a false sense of certainty and comfort, but at the end of the day, we are experimenting.

It is important to realize that from the phenomenological perspective, qualities have a hierarchy. The higher the level of the athlete, the more one needs to dig deeper and with a finer resolution to figure out rate limiters that need to be addressed. This is the difference between specialist (e.g., powerlifter) versus generalist (e.g., soccer player) and their approach to strength training. From an analytical perspective, in my opinion, this finer differentiation is missing. They both need maximum strength, hypertrophy, and the rate of force development. But they have different phenomenological qualities that are required, and hence training will be different.

To wrap up this philosophical treatise on qualities, please consider the gross phenomenological strength qualities defined by coach and legend Dan John (John, 2017):

I love using goofy names to explain concepts to athletes. Anaconda strength is the internal pressure we must exert to hold ourselves steady against the forces of the environment or implement. A highland game athlete tossing a caber is fighting forces in every direction, yet maintaining his or her body as “one piece.” Anaconda strength is the body squeezing and the inner tube of the body pushing back to keep integrity.

ARMOR BUILDING

This is the kind of training that fighters, football teams, and rugby athletes already understand. Armor building is the development of calluses or body armor to withstand contact and collisions with other people and the environment.

ARROW

This is the concept of learning how to turn yourself into stone. In football, this is the contact in tackling and blocking; in throwing, it is the block to put the energy into the implement.

This might seem very similar to (1) Maximal Strength (Anaconda Strength), (2) Hypotrophy (Armor Building), and (3) Explosive Strength (Arrow), and it actually is similar, but it is defined more from the phenomenological perspective, and as such, it will make more sense to the average soccer player or the head coach, because they think and understand “phenomena” rather than scientific abstractions (“Yeah, this method will increase your intra-muscular fast-twitch coding, which should transfer to you being more explosive on the pitch”, versus “This will make him ‘snap’ out of defender’s reach, like shot from the sling”)

Figure 2.6 Phenomenological” classification of strength training objectives

We can see that these objectives are very meaningful, but not very precise (see Figure 1.1). Although I might use these objectives when categorizing set and reps schemes, I am by no means forcing anyone to use these types of classifications – use whatever is meaningful and actionable to you. Having said that, I might still use different categorizations when defining set and rep schemes (i.e., general strength schemes, maximal strength schemes, hypertrophy schemes, and so forth). In my view, Dan John’s objectives give us the lowest resolution categories that can guide our decision-making while using the coaches’ language.

Two additional categories that I added to Dan John’s model are (1) Mongoose Persistence, which is your usual MetCon, Strength Endurance, and Explosive Endurance or any other dangerous definition you might use, and (2) Vanilla Training.

Mongoose Persistence represents the ability to prolong work, to reduce rest between bursts of strength and explosive power feats, and so forth. Why “Mongoose Persistence”? Because mongooses fight snakes, and we already have “Anaconda Strength” in there. When it comes to team sports, I am not very convinced this should be a viable strength training objective, but it can certainly have some importance, although small (i.e., core circuits, off-legs conditioning for the injured, and so forth).

Vanilla Training refers to your average low intensity, control, stabilizing, prehab, Pilates type of work. If you ask Dan Baker, that is around 90% of my training time (he saw me training a few times).

Since this manual promotes multi-modal thinking (pluralism), there might be multiple categorizations that have functional significance for you in your own context. One does not need to use an analytical-‘unbiased’-’objective’ scientific approach to objectives categorization, but one certainly needs to understand those disciplines (necessary versus sufficient discussion). You certainly are not a useless piece of shit if you are not using a scientific analytic approach, and I want to empower you to build your own categorization based on your functional significance and phenomenology.

Taking a phenomenological stance, anaconda strength, armor building, vanilla training, mongoose persistence, and arrow is very potent as a forum for action when it comes to strength training for team sports athletes. Powerlifters and other strength-based athletes might need more resolution in the categorization because they have different phenomena they need to wrestle with. Dan John’s categorization of objectives is more than enough for a team sport and other non-strength athletes (i.e., strength generalists).

Dan John Four Training Quadrants

It is very easy to get lost in the number and level of qualities that one might need to develop. One quite handy model that helps in orientation is Dan John’s model of four training quadrants (John, 2013) that is based on two continuums:

Responses