Interview with Israel Halperin

Imagine this in a single person: experienced Muay-Thai (kickboxing) fighter, experienced coach of world class fighters and a “nerd” (i.e. researcher). Well, we have a potential contender: Israel Helpering.

Israel is someone that I can talk all day long – very experienced, open, humble and honest person. We have spent some time on Skype while I was still in Doha and I honestly hope that I will meet him one day and hopefully train/collaborate with him as well.

Without further ado here is the interview. Enjoy

Exercise Physiology laboratory, Canada 2013

Mladen: Israel you are accomplished MMA & Thai/Kickboxing athlete, coach and a researcher. Can you please expand on who you are, what you do, and what are your future plans?

Israel: Thanks for having me, Mladen. I am an ex-competitive combat athlete, a kickboxing and S&C coach, and a present day PhD scholar with Edith-Cowan University in conjunction with the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS). I work at the AIS Combat Centre, a job that includes testing and monitoring athletes, and providing overall support for the four Olympic combat sports. Not surprisingly, my research interests concern the combat fields, an area I hope to continue studying in the future.

Mladen: When it comes to physical preparation of combat athletes, what are the important things to be considered and what are the things that are still being done and are waste of time?

Israel: In my opinion there are no simple answers. The relevance/irrelevance of different training components is not absolute, but depends on the athlete and her/his needs. Whereas one athlete could benefit from a specific training block, its implementation would be a relative waste of time for another. By “waste of time” I do not mean that it is completely useless. Rather, it would be a waste of time compared to an individually tailored training program. This, I find, is an important distinction. The question is not if something works or not. After all, most sane training strategies will elicit a positive outcome. The question is whether one could use limited training time in a smarter fashion. This question can only be answered on an individual basis by a coach who knows the athlete and his/her needs.

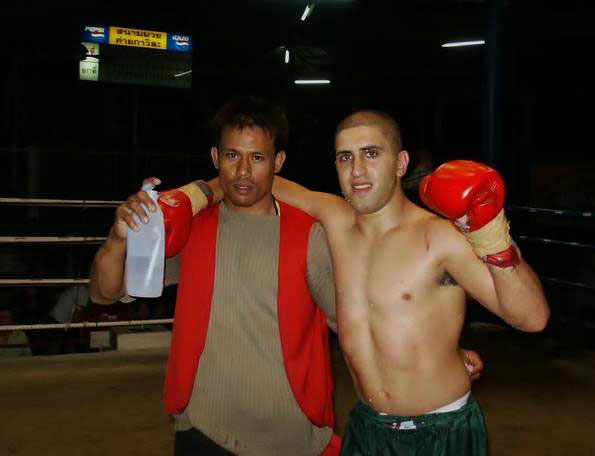

Post fight. Thailand, 2004

Mladen: How would you structure a preparation for an amateur and professional fighter – someone who has more “regular” fights as opposed to someone that have a fight 1-2 times per year? Can you expand the periodization aspect and why do you believe certain approaches work better/worse than others (e.g. mixed-parallel vs. block-sequential approaches, specific vs. general, low-intensity vs. high-intensity conditioning and so forth)? How would you approach such a problem?

Israel: While I do favor certain exercises and approaches, I do not repeat the same program with any one athlete. I prefer to let the program emerge and evolve based on a number considerations listed below in no particular order.

Evaluation in combat setting. I observe the athletes perform in their competitive environment: sparring, training, and competitions. I then try to identify objective measures that can be addressed in training. For example, are their punches explosive? Are they fit enough to last five rounds?

Assessment of Movement abilities and fitness level. I assess the physical attributes of the athletes as manifested in fitness setting. Can they squat properly? Land from a jump without their knees inwardly clasping? Perform 10 strict pull-ups? With This phase I explore the exercises that can be used to formulate a training plan as well as to expose weak links. My experience taught me to approach this stage with minimal expectations. There is great variability in performance irrespective of the athletes’ competitive status.

Injuries. Most combat athletes suffer from at least one old injury that is aggravated by certain exercises. They also tend to accumulate minor injuries during combat training (e.g., receiving a strong leg kick during sparring). Such injuries require modifications of either the overall program or in a given session. Thus, preparing plan B, and even plan C, is advisable when working with such athletes.

The Athlete’s perceptions. I constantly ask the athletes for their opinions and preferences regarding the program as a whole, exercises selection, number of sets, etc, and introduce modifications accordingly. Athletes need to feel comfortable with their training to maintain a high degree of motivation. Listening to their inputs and acting upon them is an effective strategy to gain trust and increase self-confidence. Both athlete and non-athletes feel better about themselves and their abilities when provided with a sense of control.

Coordinating with the head coach. A successful program involves the head coach. Otherwise the athlete can be placed in a stressful situation, torn between the physical preparation and the head coaches. This is a distressing and unfortunately common situation. A compromise on some details of the program may be necessary to avoid it. If the head coach is against a certain approach or exercise, it is best to consider an alternative. We have to decide if we want to be right or smart in the way we response to such situation. Being smart usually leads to better results in the long term.

Time to the next competition(s). The training plan changes significantly as a function of the date of the next bout. For example, I prefer to emphasize maximal strength and power away from a competition, and high-intensity conditioning circuits as we get closer to the event. However, long-term planning is often difficult because combat athletes are frequently invited to compete on short notice e.g., as a replacement of injured athlete.

Weight class. Combat athletes frequently reduce their weight before their competitions. In other situations they need to gain weight. Both loss and gain of weight should be considered when planning a program. For example, a world champion kickboxer that I coach is having a hard time finding competitions at his weight category. Accordingly, we have now decided to step up a category. This has significant implications on our training and we now emphasize strength training to a greater extent. We may eventually consider a lower weight category which will have an opposite effect. That is, we will do less strength training.

Environmental constraint; gyms, weather, etc. Not all gyms have the equipment necessarily for the implementation of the ideal plan. Indeed, training athletes in their home gyms sometimes entails working with as little as a pull bar and light dumbbells. An additional factor to be considered is adaptation to the local weather. I once planed a block of outdoor sprints ahead of time but failed to consider the effect of freezing rain.

As illustrated by these considerations, and there are more, it is difficult to speak of universal training needs of combat athletes. Each athlete has different needs, preferences, injuries, head coaches, weight class, timelines and environmental constrains. These need to be considered when designing a program. For these reasons, I am somewhat puzzled by the strong opinions some coaches hold concerning the relative effectiveness of certain programs. Personally, after nearly 20 years of involvement in combats sports as an athlete, coach, and scientist, I now have more doubts than ever before. To conclude my answer I would like to share a quote by the well-known physiologist, Claude Bouchard, which captures my overall coaching philosophy:

“Most exercise biologists still consider the heterogeneity of scores in response to training as a nuisance. This is clearly the wrong attitude to adopt. Indeed, individual differences in response to regular exercise are generally beyond measurements error, largely not random, and are thus informative in terms of the adaptive mechanism involved.”

Cornering Kickboxer Chris Burridge, Australia 2015

Mladen: Can you tell us more about the research you are doing and how can that be applied to the real world of coaching athletes?

Israel: Currently I am involved in a number of research projects, most of which deal with combat sports. First, I have great interest in the effects of augmented feedback on performance. This is motivated by clear memories from my days as a competitor as to how certain cues, feedbacks and instructions strongly affected me for better and for worst. Now as a coach, I constantly wonder about the type of feedback and cues I should provide to my athletes in training and competitions. Accordingly, I decided to focus my PhD thesis research on this topic. Thus far, the results of pilot study suggest that certain types of cues and instructions strongly affect performance, even among highly trained athletes. For example, elite boxers, kickboxers and Taekwondo athletes kicked and punched faster and harder after receiving external focus of attention instructions (“focus on kicking/punching the pad as fast and as forcefully as you possibly can”) compared to internal focus instructions (“focus on moving your arm/leg as fast and forcefully as you possibly can when you kick/punch”). I am now in the process of developing this project to incorporate additional types of instructions and cues. A related project involved a field study. While my experience has taught me that coaches use certain cues and instructions more than others, I have now attempted to quantify this observation by recording the instructions given by boxing coaches between rounds during the Australian championship earlier this year. We are presently analyzing the results.

My second interest concerns the relationships between different fitness variables and combat performance. We are now approaching the end of a study of elite boxers examining the correlations between power/strength measures and punching performance such as impact force and velocity. While it seems clear that lower limbs strength and power are associated with punching impact forces and velocities, demonstrating that such relationship indeed exists is an important step. Such results could make our lives easier when negotiating the importance of lower limbs exercises with combat coaches who resist the idea.

Finally, I believe in the merit of well-designed single-case studies. While their limitations are clear it nevertheless seems reasonable to benefit from my access to some the best combat athletes in the world and study aspects of their training. We are now in the process of submitting the results of two such case studies. In one we examined how a world champion kickboxer responded to self-selected vs. prescribed order of delivered punches. In the second we investigated how various boxing specific and fitness related strength/power tests varied during the 3 months training phase of an elite professional boxer preparing for a state title bout. These case studies are examples of how sport scientists and coaches can work together to mutual benefit. Indeed, when planning future research projects, I specifically consider possible benefits to the coach

Responses