Tactical Periodization and the Pattern Morphocycle: Integrating Theory and Practice

Introduction: The Game as an Unbreakable Whole

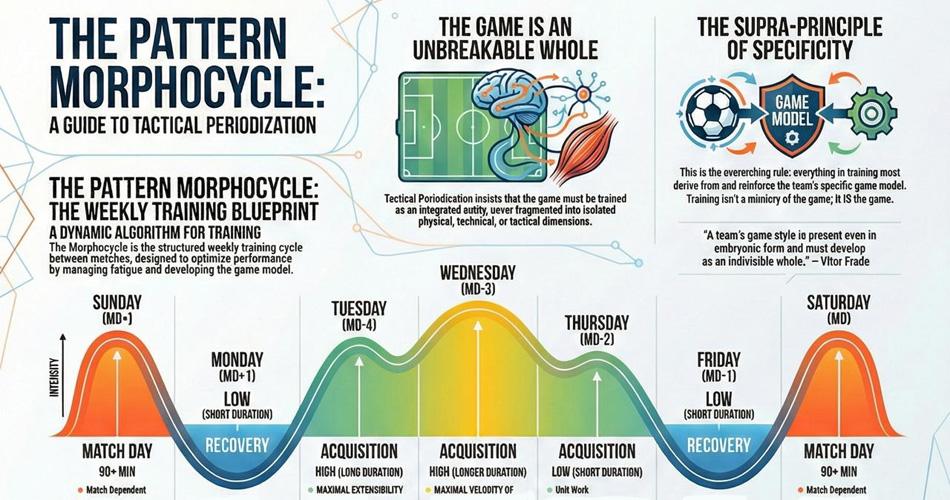

Tactical Periodization (TP), as developed by Vítor Frade, is a systemic-enactive training methodology centered on a an evolving and adapted game model, representing the desired style of play and underlying principles of a team. Central to TP is the Pattern Morphocycle, often termed the ‘mother cell’ of the methodology (Reis, 2018), a structured yet adaptive weekly training cycle aligned consistently with the game model throughout the season (1). At its core, TP emphasizes the concept of ‘unbreakable wholeness’, insisting the game be treated as an integrated entity rather than fragmented into isolated physical, technical, or tactical dimensions.

In addition, a core tenet underlying all of TP is the Supra-Principle of Specificity. This overarching principle mandates that everything in training must derive from and reinforce the specific game context. All training exercises and loads are interrelated components of one coherent whole aligned with how the team plays. Felipe Castillo Villa (2025) emphasizes that the three key training principles of TP: Propensities, Horizontal Alternation, and Complex Progression “should never be viewed independently” but rather form an interconnected unity under the Supra-Principle of Specificity (2). It is this unity that gives “articulation of sense,” meaning that every drill, session, and cycle has a clear purpose connected to the game itself. In practical terms, specificity means that training tasks always resemble game situations in structure and intention. By consistently training the way we intend to play, we ensure that players develop relevant skills, decision-making, and even physical conditioning that directly transfer to matches.

Frade, as discussed by Reis (2018) illustrates this vividly, noting that ‘just as a river is a river even at its source, a team’s game style is present even in embryonic form and must develop as an indivisible whole’’ (1). From day one of training, the team’s style of play is nurtured in an integrated fashion, never broken into disjointed pieces.

All the following sections are put together via reflections from my experiences and understanding learned from the methodology adapted to fit within some of the contexts in which I have been previously employed in. The practical examples are adapted to different professional contexts, and some of the content have been illustrated as hypothetical examples. In addition, I would like to thank the support, collaboration, and inspiration that has been provided by mentors and colleagues: Jorge Reis, Felipe Castillo Villa, and Milan Mirić.

Structure and Logic of the Pattern Morphocycle

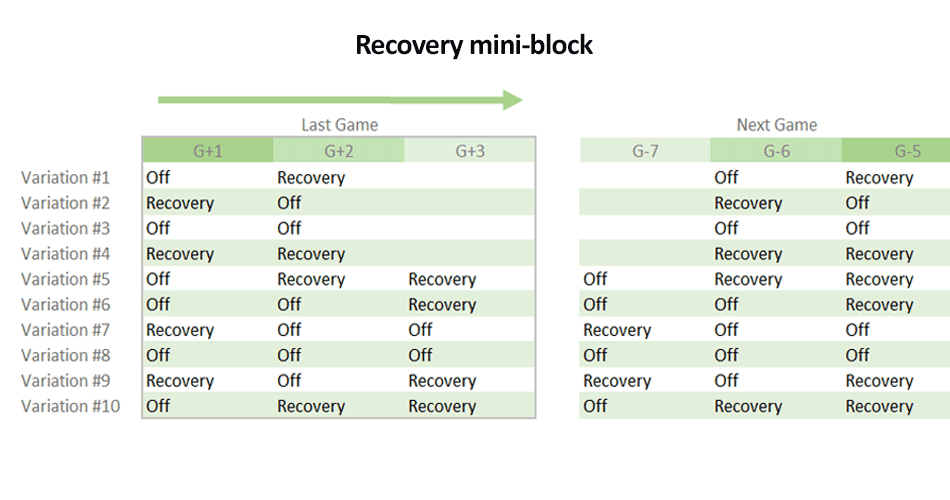

The Pattern Morphocycle refers to the structured weekly cycle of training between matches, designed to optimize performance on game day while developing the game model. Rather than a rigid schedule, it is a dynamic algorithm for training. It provides a repeatable structure yet remains flexible and adaptive to the team’s ongoing needs. In a typical Morphocycle with one match per week (although highly adjustable depending on context and fixture congestion), training days are conceptually divided into acquisitive days and recovery/regenerative days, each with distinct but complementary purpose. The mid-week acquisitive days are high-intensity sessions where players “acquire” or build Specific qualities and interactions related to the game model. These sessions impose the greatest demands physically, mentally, and tactically. The lighter days (usually immediate post-match and the day before the next match) serve predominantly for recovery, dissipating fatigue and consolidating learning, while still involving football-specific content, always with relative maximum intensity depending on the day of the week. Importantly, the distinction between ‘acquisitive’ and ‘recovery’ days is one of emphasis rather than exclusivity; even recovery-focused sessions contain tactical learning, and acquisitive sessions include restorative elements. This balance allows continuous development without overtraining, respecting the team’s overall readiness cycle.

Underpinning the Morphocycle’s logic is the idea of systematic repetition with variation. Each week the team rehearses the game model through different contextual foci, reinforcing a “habit” of play. Over time, this repetition leads to players internalizing the style of play, making it increasingly “part of the players, something more and more corporeal” as discussed by Reis (2018) (1). In other words, the tactical behavior becomes second nature. This evolution is not linear; it resembles a complex, non-linear process of growth. There are no distinct “phases” where the team first focuses on generic fitness then later tactical works; instead, tactical specificity is present from the start and continuously, growing in complexity and intensity as the season progresses. The weekly Morphocycle is the framework that ensures this continuity. By strategically organizing. the patterns of interaction (a process Frade terms ‘geometrizing’) each week, the coach essentially “tactically periodizes” the game style, linking every practice to the intended way of playing. This consistent linkage between training and playing gives meaning to every session and fosters a shared team identity. The Pattern Morphocycle thus provides the logic to manage the performance and themes for each day, guaranteeing that the team’s learning all happen in an systemic-enactive manner aligned to the ultimate goal: performing the game model optimally on match day.

Figure 1. Example of Pattern Morphocycle – Senior Football Team – Danish Superliga

Muscle Contractions in the Tactical Periodization Methodology

Within Tactical Periodization, the management of muscle contraction types is inseparable from the Supra-Principle of Specificity. Rather than viewing strength or speed training as isolated physical capacities, the methodology integrates them into the Pattern Morphocycle through two key physical-tactical emphases: Maximum Extensibility and Maximum Velocity of Contraction. Each corresponds to specific neuromuscular demands present in the game and is strategically placed within the weekly structure to achieve the desired tactical and physiological adaptations without breaking the logic of specificity as mentioned by Reis (2018) (1).

The Maximum Extensibility session emphasizes eccentric muscle actions, where muscle fibers lengthen under tension such as, decelerations, directional changes, and braking actions after sprints. These actions are fundamental in football for maintaining balance, controlling momentum, and creating stability before explosive efforts. According to Frade’s methodology, concentric/eccentric stimuli must be trained analytically; that is, in simplified, controlled situations because maximal extensibility cannot be safely achieved within open-play exercises, where game dynamics could prevent full-length eccentric expression. Physiologically, such eccentric training induces microdamage that stimulates structural remodeling and strength gains but requires significant recovery (3,4). Hence, it is typically placed four to five days before the match (MD-4) to allow full regeneration (1). Immediately following these analytical stimuli, complementary exercises with focus on meso/micro princicples are used to recontextualize the neuromuscular work, ensuring that the muscular adaptations are “anchored” within the team’s tactical model (2). In this way, even highly analytical muscular work remains consistent with the Supra-Principle of Specificity, ensuring that physical adaptations always contribute directly to football-specific performance.

Conversely, the Maximum Velocity of Contraction session targets concentric and stretch–shortening cycle (SSC) actions, where muscles produce maximal force in minimal time. These stimuli are addressed through high-intensity actions integrated into specific tactical contexts (e.g., counterattacks, or one-on-one breakaways) that demand rapid decision-making and full neuromuscular activation. By situating these drills within realistic game conditions, the session develops both neuromuscular efficiency and cognitive speed, uniting physical speed with perceptual-tactical speed. This session generally occurs two to three days before the match (MD-3/2), ensuring that neuromuscular potentiation (increased readiness for high-velocity efforts) aligns with match-day performance peaks (1, 5).

Crucially, both emphases of Maximum Extensibility and Maximum Velocity are not traditional “strength” or “speed” sessions, but specific football stimuli that reproduce the energetic, coordinative, and informational conditions of competition. They exemplify how TP transforms physical training into tactical education: every muscle contraction has a meaning, a sense, and a tactical reference. By integrating these contraction types within the Morphocycle’s oscillating rhythm (Horizontal Alternation) and connecting them back to the team’s playing principles, the methodology ensures that physiological adaptations serve tactical expression, preserving the indivisible wholeness of the game.

Figure 2. Position Specific Runs – Highlighting an Integrated Approach Where both

Maximum Extensibility and Velocity of Contraction Can Be Potentially Achieved

Figure 3a. Example of Maximum Extensibility – Fundamental Exercise

Figure 3b. Example of Complementary Exercise – Focus on Micro/Meso Principles – Buildup

Figure 4a. Example of Maximum Velocity of Contraction – Fundamental Exercise

Figure 4b. Example of Complementary Exercise – Focus on Micro/Meso Principles – Transition

Methodological Principles of Tactical Periodization

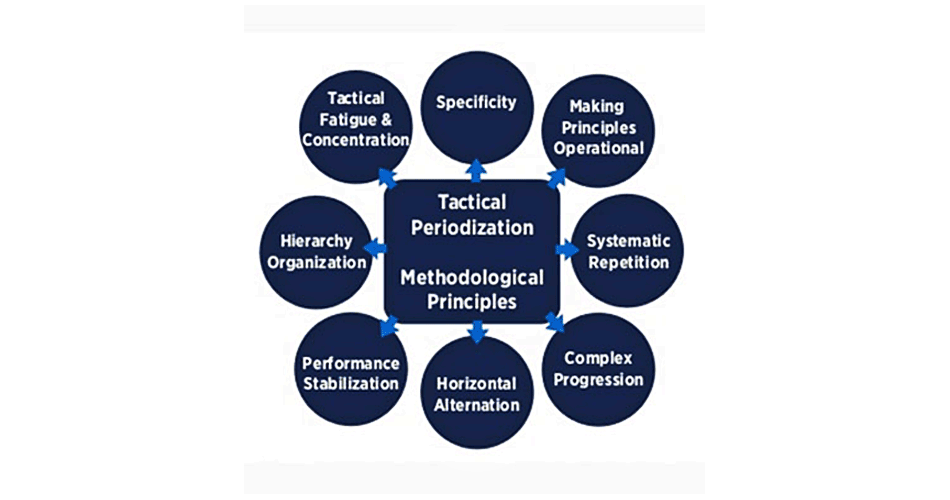

Tactical Periodization is built on several key methodological principles that operationalize the above logic. These principles work in concert, their “pattern of connection” is what concretely produces the specificity we seek in training, through the weekly Morphocycle. The core principles are often enumerated as Propensities, Horizontal Alternation in specificity, and Complex Progression, each addressing a different aspect of the training process. Below is an overview of these principles and how they interrelate:

1. Principle of Propensities

This principle entails designing training situations with specific propensities (tendencies or orientations) that reflect the game model. Instead of using generic drills, each exercise is conceived “through contexts of propensity” related to our style of play (e.g. a pressing exercise if our game model values high press) rather than a context of pure physical exercise. In practice, this means every training activity has a clear tactical intention or game moment focus, so that it inherently carries the specificity of our football. By manifesting the desired game patterns in training, we ensure “who controls energy is information” the information of our game idea guides the players’ effort (1). Additionally, propensity implies maintaining a “relative maximum intensity” (i.e., maximum intensity of concentration) in training is intense and competitive, but always relative to football actions (not maximal in an abstract physiological sense). Players work hard with the ball and decision-making, which naturally pushes them near competitive intensity in a way that’s relevant to actual match demands. This creates the “delayed effect of performances” we seek. The training performances (executed with specific intensity and intent) lead to improvement in game performance after recovery. In short, the propensity principle ensures training is always specific and high-quality, every drill is a small replica of the game, aligning player effort with the game model so that improvements in training transfer directly to match performance.

Figure 5. Build Up vs. High Press

Supra Principle of Specificity Principle:

Training ≠ mimicry; it is the Game.

Meaning in Exercise: Build-up vs 4-4-2 is trained exactly as it will be lived, not abstracted into isolated drill. not just “playing out,” but building-up as a categorical imperative of style.

Horizontal Alternation:

Meaning in the Exercise: MD-4 tactical stress: Acquisition day in Morphocycle on Meso-Micro Level

Complex Progression:

Principle: From simple → complex, conscious → unconscious → fluent.

Meaning in Exercise: The exercise itself self evolves:

- Stage 1: 7+GK vs 6 (numerical advantage for build-up)

- Stage 2: 7+GK vs 7 (adding balance to pressing side)

Complexity gradually increases without breaking specificity.

Propensities:

Principle: Constraints guide but do not dictate; they invite interaction.

Meaning in Exercise: Central corridor scoring = propensity for central risk-taking; pressing trap zones = propensity for defensive regains.

- Meaning: The Game Model gives purpose → “we progress with control.”.

- In the task: Exercises mirror the game → principles + all 4 moments appear naturally.

- Habit: Over time, repetition wires these behaviours into collective automatisms / aligning team intention

2. Principle of Horizontal Alternation

Specific training induces fatigue; it must be strategically alternated with lighter sessions to allow recovery without breaking the continuity of training.This is the idea of horizontal alternation across the week, to manage complexity, in an oscillating rhythm. The alternation is done “in Specificity”, meaning even the lighter days maintain football-specific work (not complete rest or unrelated exercise), but with reduced load or a different emphasis. For example, after a very intense tactical session one day, the next day might focus on slower-paced strategic review to actively recover. Frade emphasizes “people get tired and need to rest’’ (1); hence, there is Horizontal Alternation to dose. This principle is grounded in physiological reality; the body and mind require cycles of stress and regeneration (i.e., the self-renewal cycle of living matter). Classic exercise science principles like the Arndt–Schultz law support this, weak stimuli have little effect, moderate stimuli enhance adaptation, but excessive stimuli are harmful. In our context, that means if every day were high-intensity, players would overtrain (“destroy” performance); conversely, too many easy days and they would not adapt. Horizontal Alternation finds the optimal middle ground by dosing training stress followed by adequate recovery, reinforcing the need for this. Practically, the weekly pattern gets ‘’the human football players“ used to a weekly pattern that contemplates the various dimensions of our gameplay” without burning them out. For the team as a collective, alternation also ensures all players can perform together without some being excessively worn out, the whole team follows the same wave of fatigue and freshness. Notably, TP identifies the midweek heavy sessions as producing “tactical fatigue”, fatigue that comes from executing our style at high intensity. This kind of fatigue requires specific recovery (replenishing the “highly energetic substances” like muscle glycogen, and also mental rejuvenation) so that players can be ready for the next peak intensity effort. Thus, Horizontal Alternation is the principle that manages the flow of fatigue and freshness across the Morphocycle, ensuring players supercompensate in time for match day. It embodies the idea that training adaptation happens during rest, just as memories consolidate during sleep, the improvements from training are “processed, somatized and made conscious” during periods of pause. By alternating stress and restitution within specific football contexts, we maximize adaptation while minimizing the risk of injury or performance drop-offs.

3. Principle of Complex Progression

This principle deals with the progressive increase of complexity in the training process. It recognizes that both across a single week and over the longer term, we should evolve from less complex to more complex tasks in a non-linear, dynamic progression. Within a given week, for instance, exercises might start with smaller-scale situations or isolated sub-principles and build up toward larger, more complex game-like scenarios as the week advances. Over the course of a season, training might move from basic implementation of the game model toward finer details and higher tactical nuance. The key is that progression is not merely a linear increase in physical load, but an increase in tactical and cognitive complexity “from less to more complex in the specificities of specificity” as it’s sometimes phrased (1). Frade notes that this progression must be “sustainable”, which is why it is intertwined with the other principles, we cannot add complexity without regard for fatigue or the quality of learning. Complex Progression also has a psychological dimension, it’s about the “relationship between mind and habit” in learning. Early on, players rely on conscious understanding (the know-what and know-why), but through repetition and appropriate challenges, they gradually form habits (the know-how) that become automated. As Damasio (1994) describes, there is a transfer from conscious control to non-conscious control with practice, through slow education, conscious skills become reliable subconscious habits that align with our intentions (6). In training terms, we must design a sequence of challenges that continually push players just beyond their current comfort zone, forcing adaptation and learning without causing confusion or chaos. The principle of Complex Progression thus ensures that training respects the player’s learning curve, starting from action by doing and progressively stimulating reflection/understanding. Initially “the primacy is in the action, in doing, practicing, and not in the rationalization”, which allows players’ implicit skills to form; later, through guided feedback, players attach explicit knowledge to those skills “knowledge about the know-how” to further refine them. This mirrors the concept of enactive cognition, where cognition emerges from the non-linear interaction between the subject, his/her intentions and the environment., and only subsequently can be articulated. By the end of a well-structured progression (progression being non-linear, is not always evolutionary; in many cases, we must go back, since the learning process is also lost), players have both ingrained habits and conscious insight into the game model, a dual attainment of practical and theoretical mastery. In summary, Complex Progression keeps the training process evolving in difficulty and complexity in harmony with the team’s development, preventing stagnation and ensuring the highest levels of performance are reached in a methodical, coherent way.

These three methodological principles work together as one. In fact, Frade emphasizes that it’s the connection of Propensities, Horizontal Alternation, and Complex Progression that allows Specificity to be realized (1), concretely taking shape as the weekly Pattern Morphocycle, the “uninterrupted weekly presence” of our game model in training. Through Propensities, we ensure every session is specifically about our game; through Horizontal Alternation, we ensure a balanced rhythm of acquisition and recovery for sustained performance; through Complex Progression, we ensure continuous development and adaptation. Together, they make Tactical Periodization a robust framework that is far more than a “recipe”, it is a scientific, pedagogical and practical approach that molds training into a living, adaptive process aligned with the nature of football itself.

Fatigue, Performance, and Recovery in the Morphocycle

One of the key challenges any training plan must address is how to balance fatigue and recovery so that players perform at their peak on match day. Tactical Periodization’s pattern Morphocycle is explicitly designed to manage this balance, leveraging the above principles. In the TP view, fatigue is not the enemy per se; rather, fatigue is a necessary byproduct of the intense “performances” we seek in training, and it plays a role in triggering adaptation to the team’s playing style. What matters is the timing and specificity of fatigue so that it leads to improvement instead of impairment. This idea is captured in the concept of the “delayed effect of performances”. Unlike classical periodization which speaks of a delayed effect of training loads, TP reframes it as the delayed effect of performance, meaning the high-quality game-like performances in training are the stimulus that, after a recovery period, yield improved future performances. In simpler terms, we push players to perform our game model intensely in midweek sessions, they accumulate fatigue from these efforts, and then as they recover, the benefit (supercompensation) manifests as enhanced performance capacity by the next match. Crucially, this benefit is specific because the stimuli were football actions and decisions, the improvement is in football performance, not just generic fitness. “It’s a type of football performance, and that’s important,” notes Frade the muscles, metabolism, etc. adapt in the specific way needed for our style of play (1).

To make this work, the Morphocycle carefully times the sessions based on complexity. Typically, the most intensive training (i.e., intensity with maximum concentration but always relative maximum intensity) focusing on macro principles is placed ~72-96 hours before match day, to allow full recovery and adaptation by game time. This aligns with sports science on muscle glycogen restoration, neural recovery, etc., but TP conceptualizes it in tactical terms. The fatigue players experience after those acquisitive sessions is “tactical fatigue” fatigue that comes from executing complex game situations at maximum relative intensity. As we saw, the Horizontal Alternation principle ensures there is subsequent recovery time within a football context for those fatigued systems to replenish. Modern physiological concepts reinforce this approach. The self-renewal cycle of living matter, first proposed by Roux (1881) in the late nineteenth century, suggests that biological tissues undergo continuous cycles of breakdown and renewal and therefore require recovery time for adaptation to occur (3). Building on this idea, Wolff’s law described how bone remodels along the lines of mechanical stress, implying that tissues strengthen only when appropriate load is followed by sufficient regeneration (8). Similarly, the Arndt–Schulz law states that small doses of stress stimulate function, moderate doses strengthen it, and excessive doses destroy it (9). Tactical Periodization applies these classical biological principles by modulating training intensity throughout the week, never allowing fatigue to accumulate to destructive levels. Instead, moderate-to-high stresses in specific football contexts are introduced before periods of recovery, ensuring that each “exaltation” phase, the window of improvement, occurs without tipping into paranecrosis or overtraining. In Vítor Frade’s terms, the goal is for overcompensation to be tied to performances, not to abstract physical loads; the coach seeks controlled micro-damage that stimulates adaptation, not tissue destruction (1,4). Another important aspect is that recovery in TP is not simply physical rest, it is also when learning is consolidated. Neuroscience draws parallels between sleep and memory, during sleep, the brain reactivates and solidifies the patterns experienced during the day, which is essential for long-term memory formation. TP leverages this by alternating strenuous “learning by doing” days with lighter days where players can reflect, absorb, and mentally encode what they practiced. In essence, recovery days serve as both physical regeneration and mental consolidation days. This holistic view of recovery stems from integrative physiology and network physiology perspectives, the recognition that physiological systems (e.g. nervous, muscular, endocrine, etc.) are deeply interconnected and adapt together, as a network. Fatigue is not only muscle glycogen depletion, but also central nervous system fatigue, hormonal fluctuations, emotional stress, etc., all interconnected. Therefore, the recovery must also be multifaceted, not just rehydration and nutrition, but also sleep, relaxation, positive emotional environment, and reactivation of the mind in low-stress conditions. By treating players as complex adaptive systems rather than simple machines, the Morphocycle approach optimizes performance. It accepts that ‘’we cannot isolate and predict adaptation from one variable’’; instead, “patterns emerge as a product of nonlinear integration of personal and environmental influences” in complex systems. Hence, TP’s comprehensive approach: manage the training process with an eye on the whole player and the whole team, rather than chasing isolated metrics.

In summary, the Pattern Morphocycle logically sequences the week to induce a wave of fatigue and recovery that leads to a peak on game day. Through specific high-performance training we create the needed stimulus, and through planned recovery we ensure that stimulus translates into improved collective performance. The entire process upholds a key TP mantra “train what you want to see in the match, then allow time for it to be absorbed.” This way, performance is built and rebuilt each week in a sustainable cycle, minimizing injuries and maximizing the “delayed effect”, the qualitative improvement of the team’s game style over time.

Philosophical and Neuro-Physiological Foundations

The Tactical Periodization framework is underpinned by a rich blend of philosophical ideas and neuro-physiological science, which together justify why this methodology works. At a high level, TP aligns with a complex systems view of human performance and learning. Football is not a simple sum of physical, technical, or mental parts, but an emergent phenomenon arising from their interrelations. This view echoes modern scientific paradigms like integrative physiology (i.e., studying the organism as a whole system) and enactive cognition (i.e., understanding cognition as arising from active engagement with the environment). It’s insightful to see how thinkers such as Catherine Malabou and Antonio Damasio coming from philosophy and neuroscience have ideas that resonate strongly with TP’s approach.

Neurobiology and Plasticity

One of the key mechanisms explaining how players adapt to a game model in Tactical Periodization is neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity to reorganize its neural circuits in response to experience. As philosopher Catherine Malabou (2008) describes, plasticity is not a passive flexibility but a form-giving power, the brain continually transforms its own structure and function through activity, shaping the emergence of mind and behavior (10).

Within the Tactical Periodization framework, training acts as a generator of directed neural plasticity, where each repetition of a football-specific task sculpts the brain in accordance with the team’s game model. Through systematic exposure to specific tactical situations, decision-making under pressure, and contextualized movement patterns, players gradually form neural connections that mirror the informational structure of their style of play (1,2). Over the course of successive Morphocycles, the players’ nervous systems become optimized for recognizing affordances and responding to the constraints inherent in the team’s tactical identity.

Malabou’s notion of a “plasticity of agreement” the alignment between the neuronal and the mental captures this process well: repeated, meaningful football experiences bring the players’ physical neural adaptations and subjective understanding into synchronization (10). In practice, this manifests as what Frade describes as a “mental landscape of play”, an internalized topography of relationships, spaces, and possibilities that must “be born first in the players’ heads before it can manifest on the pitch” (1). Importantly, this learning is not symbolic or representational in the traditional cognitive sense. It is enactive, players do not store abstract rules but construct understanding through interaction with the environment. As Varela et al. (1991) argue, cognition “emerges from the ongoing coupling between perception and action,” and knowing is inseparable from doing (7). The player’s tactical knowledge, therefore, arises not from instruction but from embodied experience: they “learn the activity by doing that activity… not another one” (1).

In this sense, the Pattern Morphocycle functions as an engine of guided neuroplasticity, systematically shaping perception-action couplings through specific football contexts. Repeated tactical scenarios activate particular neural pathways linking sensory information, motor execution, and emotional feedback until the response becomes both efficient and meaningful. Over time, this yields what Frade calls an “unconscious metabolic representation” of the game model: a tacit, embodied readiness that allows players to execute complex tactical patterns almost reflexively, while retaining conscious flexibility to adapt as needed (1). This complementarity between conscious and non-conscious control systems, described in neuroscience by Antonio Damasio, underlines the process through prolonged practice, deliberate (conscious) control gradually trains automatic (non-conscious) systems, enabling fluid, intuitive performance (6). Decision-making in this framework is not computational or symbolic, it is emergent from the lived, embodied history of specific game interactions (6,7). Thus, Tactical Periodization’s reliance on specificity and repetition is not mere routine but a deliberate neurobiological strategy: it uses the brain’s capacity for self-transformation to engrave tactical principles into both the body and mind. The process is dynamic and ongoing form and identity in living systems are never static but constantly reconstructed through use (1,10). Each training week, by exposing players to the meaningful informational patterns of football, becomes an exercise in guided neural and behavioral adaptation. In this way, TP respects players as plastic and adaptive beings and transforms training into an integrative practice of embodied cognition, where learning, perception, and performance evolve together in a living, self-organizing system.

Cognition, Emotion, and Enactive Learning

The Tactical Periodization approach embodies the logic of enactive cognition, which conceives knowledge and skill as phenomena that emerge through the reciprocal coupling of perception and action rather than through the internal manipulation of symbolic representations (7). In this framework, learning occurs as players interact with dynamic game environments, continuously reorganizing their understanding through action.

Within the football context, this means that tactical awareness and decision-making arise from doing football from perceiving, acting, and adapting within the flow of realistic situations rather than from passively receiving instructions or abstract theoretical input (1,7). This logic explains why the methodology insists that “the primacy is in the action, in doing, practicing, and not in the rationalization”: understanding is a consequence of embodied experience, not a pre-condition for it (1).

In the enactive perspective developed by Varela et al., (1991), cognition is not computation but enaction, the continuous situated creation of meaning through sensorimotor activity (7). Players acquire tactical intelligence by developing sensorimotor schemes that link perception, movement, and intention; these schemes are refined as players adapt to the constraints of the match environment (12). Consequently, the Pattern Morphocycle becomes a designed ecosystem of perception-action experiences where players co-construct knowledge about the game. This systemic, ecological process ensures that learning is embodied and context-specific, resonating with the methodology’s Supra-Principle of Specificity (1).

The neurobiological complement to this enactive logic is provided by Antonio Damasio’s work on consciousness and emotion. Damasio’s research shows that deliberate, conscious regulation of behavior gradually trains non-conscious neural systems, transferring control from explicit to automatic circuits through repetition (4). This mechanism explains how, across successive Morphocycles, players who initially require conscious guidance from the coach later act intuitively, executing tactical behaviors without deliberation. Within Tactical Periodization, the coach intentionally facilitates this education of the unconscious: context-rich, repeated football actions strengthen implicit neural pathways until performance becomes fluid and instinctive, yet still open to conscious reflection when needed (2,6).

Decision-making in this model is not an internal computation detached from the body but an emergent, embodied phenomenon. As Varela and colleagues argue, cognition is distributed across brain, body, and environment (7). Damasio’s somatic-marker hypothesis supports this by demonstrating that emotional and bodily feedback, somatic markers serve as rapid, adaptive guides for behavior under pressure (11). During Tactical Periodization sessions, players repeatedly experience emotionally charged football situations that create somatic references for future matches: the satisfaction of a successful press, the tension of defending while fatigued, or the anxiety of being outnumbered. These affective imprints later bias real-time decisions toward actions that align with the team’s game model (11). The process is therefore not symbolic reasoning but embodied prediction: decisions arise from the interplay between the player’s lived history of training experiences and the immediate informational landscape of the match (7,11). From a systemic viewpoint, the three evolutionary layers of the brain, brainstem, limbic system, and cortex are all engaged within the methodology’s integrated training design. The brainstem is activated through the physical urgency of competitive drills (survival and energy regulation); the limbic system through emotional arousal and social interaction; and the cortex through reflective analysis, dialogue, and conscious tactical understanding (6,11). By orchestrating exercises that simultaneously stimulate these interconnected layers, Tactical Periodization respects the embodied totality of the player: physical, emotional, and cognitive dimensions operate as one adaptive system. In this sense, the methodology does not juxtapose body and mind but unites them through the living wholeness of training.

Ultimately, Tactical Periodization fuses Varela’s enactive philosophy and Damasio’s neurobiological evidence into a coherent methodological synthesis. The former provides the epistemological grounding for knowledge as enacted through context while the latter offers the physiological mechanism: how repetition, emotion, and bodily feedback consolidate that knowledge. Both converge within the Pattern Morphocycle, where each football-specific exercise functions as a site of embodied learning and neurobiological adaptation. The outcome is not a player who merely “knows” tactics conceptually but one who feels, perceives, and acts tactically in real time: an intelligent performer shaped by the enactive logic of the game itself.

Ethical and Cultural Framework

Beyond science, TP carries an implicit ethical and cultural dimension. Ethically, it treats players as subjects in the learning process rather than objects of training. The methodology demands that training exercises have meaning, they are not arbitrary punishments or mindless laps, but purposeful scenarios. This respects the player’s intelligence and inherent desire to play football not run marathons. There is an ethic of care for the player’s wellbeing; by monitoring fatigue and never divorcing training from context, the coach shows respect for the interconnectedness of player’s body and mind. This is in stark contrast to old-school methods that might run a team into the ground with laps or drills that have no relation to the game, potentially causing injury or disinterest. Culturally, TP fosters a culture of shared purpose and identity. Since training is built around a specific game model that embodies certain values (e.g. creativity, aggression, solidarity, etc.), those values are continuously reinforced on the training ground. Over time, this creates a strong team culture, a feeling that “this is how we play, this is who we are.” It’s an almost ritualistic reinforcement of identity every week. The coach’s role also shifts culturally; they become a teacher-facilitator who must articulate the “sense” of every exercise ensuring players understand why they train as they do, which in turn builds buy-in and motivation. The methodology inherently has a democratic aspect, players’ feedback and understanding matter since training is a co-adaptive process; however, the final decision(s) is ultimately made by the coach. In fact, modern implementations of TP consider players as co-designers in training to some extent, reflecting a more collaborative culture. Moreover, TP doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it must adapt to local cultural contexts without losing its essence.

To sum up, the theoretical foundation of the Pattern Morphocycle spans from cellular metabolism to cognitive neuroscience and philosophy amongst many others. TP’s approach is vindicated by integrative scientific insights, the body adapts specifically to the stimuli it receives, the brain learns by doing and feeling, and humans perform best when things make sense and align with their motivations. Most importantly, the player (i.e., interconnectedness) adapts to our game. It’s a methodology that harmonizes the biological, the psychological, and the cultural. By doing so, it achieves what many traditional approaches miss, a truly sustainable development of performance, where improvements are not bought at the cost of player health or engagement, and where the “soul” of the team (its identity and style) grows alongside the physical and tactical proficiencies.

References

- Reis JC. The Pattern Morphocycle’s Sustainability: The Tactical Periodization’s “Mother Cell”. Vigo: MCSports; 2018.

- Castillo Villa F. Interaction of Methodological Principles. S.n.; 2025.

- Roux W. Der Kampf der Teile im Organismus [The Struggle of Parts in the Organism]. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1881.

- Billat LV. Interval training for performance: a scientific and empirical practice. Sports Med. 2001;31(1):13–31.

- Saltin B. Metabolic fundamentals in exercise. Med Sci Sports. 1973;5(3):137–146.

- Damasio AR. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons; 1994.

- Varela FJ, Thompson E, Rosch E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 1991.

- Wolff J. Das Gesetz der Transformation der Knochen [The Law of Bone Transformation]. Berlin: A. Hirschwald; 1892.

- Arndt R, Schulz H. Über die Wirkung kleiner Arzneimengen bei Bakterien. Z Hyg Infektionskr. 1888;4:283–308.

- Malabou C. What Should We Do with Our Brain? New York: Fordham University Press; 2008.

- Damasio AR. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace; 1999.

- Balagué N, Pol R, Torrents C, Ric Á, Hristovski R. On the relatedness and nestedness of constraints. Sports Med Open. 2019;5(6):1–9.

I want to become a member. Good tactics and explanations on these site. It help me to develop players individual and as a team.

It’s very much helpful after read that article of TP. I want to read more articles about modern soccer. Thank you so much 🙏