Balancing Physical & Tactical Load in Soccer: A Holistic Approach Part 1

AN ALL-TIME CLASSIC QUESTION; How to achieve and manage the balance between physical and tactical training? Where does a fitness coach’s work end and where does the work of the football coach start? To begin with, training to enhance physical performance is an adaptive process that involves progressive manipulation of the physical load (Manzi et al, 2010), which is the sum of the fitness coach and football coach’s work. Monitoring training load is therefore essential (as all practitioners attest to), in managing the training “dose” to ensure the desired improvements in performance are attained whilst minimizing the incidence of load-related injuries (Akenhead & Nassis, 2016; Weston, 2018). Furthermore, in modern football, match analysis and technology provide coaches with important information on the physical, technical and tactical demands of the game, highlighting each player’s performance (Sarmento et al 2014; Rein & Memmet 2016).

Every action performed in the game includes a decision (tactical part), an action or motor skill (technical part) that requires a particular movement (physiological part) and is directed by volitional and emotional states (psychological part) (Delgado & Mendez-Villanueva, 2018). How well are we taking into account this information? How do we implement this in our daily training process?

Every football or fitness coach should always ask him/her self:

WHY

we have to reconsider our daily training process and game model?

WHAT

is our training philosophy coming from that game model?

WHEN

and how can we periodise all physical and tactical contexts?

We Train as We Play (WHY?)

“Training is worth it only when it lets you make your ideas and principles operational. Thus, the coach has to do exercises to guide his team to do what it is intended to do in the game.”

What Are the Key Aspects That We Need to Know When Designing Our Training Sessions?

A) Game Model

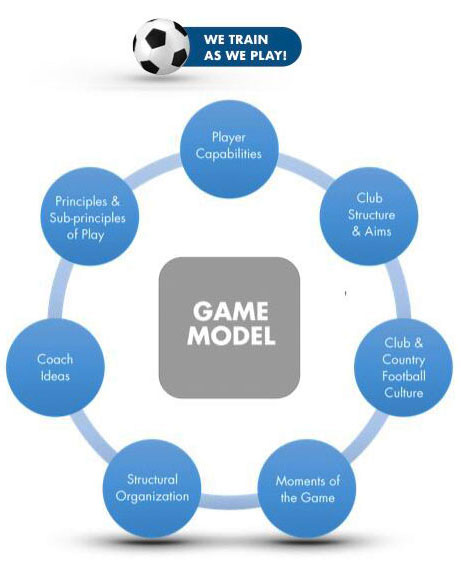

Football or Soccer (in European “sport glossary”), is an intermittent sport with a) physical demands, with changes in the speed of movement and direction (e.g., walking, jogging, high intensity running, and sprinting), b) technical actions (dribbling, passes, shots, etc.) and c) tactical principles of play (e.g., playing style, formation, positioning, etc.) which ultimately determine the outcome of the match and the overall team performance. Tactical Periodisation is a contemporary training approach in football that was recently introduced where the reference is always the GAME. Therefore, whatever you are doing in your training (physical & tactical training) should link to what you would like to see in the game. When devising your Game Model, you should consider several factors (figure 1).

Figure 1. How to build a Game Model (Delgado & Villanueva 2012).

Each team has a different game model according to their coach’s philosophy, the different profile of players that a squad has, any cultural specificities a club or country may have and so on. However, we can see coaches breaking the rules; for instance, Maurizio Sarri (current Chelsea FC coach) has the same Game Model and philosophy working in a lower ranking team as working in a big team. One of his game model’s characteristics is to find the depth playing short to attract the opponent and find the space at their back (video 1).

Video 1. How to attack the depth – Coach Maurizio Sarri (Empoli – Seria A 2015/15)

Coaches should always be prepared to adapt to the current conditions that they are facing. Moreover, we need to bear in mind that having a clear Game Model reduces the players’ uncertainty when they play and gives them more time to develop their creativity (Delgado & Mendez-Villanueva, 2012).

When coaches are building their team’s Game Model, they are building on collective patterns (team), sectorial (one line, e.g. defenders), inter-sectorial patterns (two lines between them, e.g. defenders with midfielders), and individual (one player) (Delgado & Mendez-Villanueva, 2018). Furthermore, learning from the coaching education courses, a coach’s plan consists of a) formation (system of play), b) tactics (individual-lines-team), c) special tactics, and d) strategy. It is essential to analyze our team’s way of playing (formation/tactic) and identify what are the tactical demands of each position (a Right Back may have different demands from system to system). It is not suggesting, players doing individual “positional” fitness training. For example, it will not be beneficial for a Right Back to try simulating his game in the fitness training context without any tactical requirements. It would be better for him to do football training in his position, executing the same time all his tactical demands.

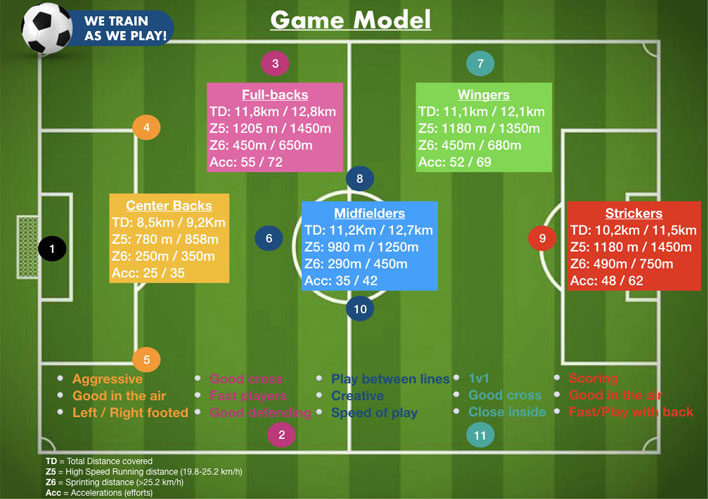

Nevertheless, we have to identify the physical demands of that Game Model and try to train them first with football. Fitness training should always be complementary to football training; primarily to target injury prevention and then to improve performance. In order to achieve this, positional (averages and max) and individual (averages and max) would be fundamental elements to start building the team’s profile; in order to help coaches adjusting the training prescription (figure 2).

Figure 2. Game model physical averages max tactical characteristics by position random data

When looking at players’ performance in a game, we should consider the high variability in players’ running performance from game to game (Al Haddad et al, 2017), especially in high speed running (Gregson et al 2010; Al Haddad et al, 2017). Moreover, we have to bear in mind that when using these physical parameters to analyze our Game Model, we only quantify the movement profile of our game, and not the non-locomotor activities such as tackling, kicking, duels, jumping that could metabolically influence the player’s performance. In the end, the most important is the ability to generate a high physical output during the game, without the significant compromise of the technical, tactical or psychological aspects of match play (Delaney, 2018).

B) Moments of the Game

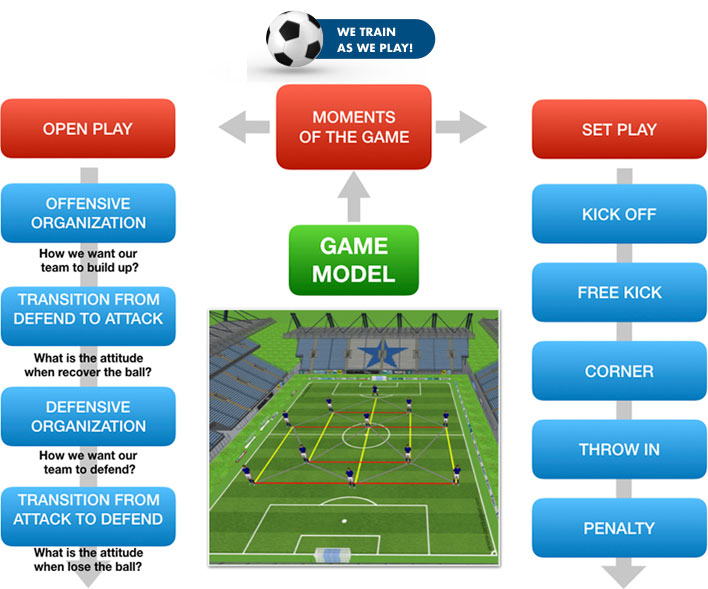

Another important aspect, directly linked with the Game Model, is the moments of the game. Analyzing a team’s game model, a key factor of a team’s success is to train the moments of the game which consist of, a) Open Play, with the four moments of the game, and b) Set Play, (offensive/defensive) consisting of kick-off, free kick, corner, throw-in and penalty (figure 3).

Figure 3. Moments of the game – Open & Set Play

Building our Game Model, we should have a clear philosophy (from Macro-principles to Sub-principles) of what our team is doing in each phase. For example, in Offensive organization, our Macro principle could be Ball Possession, to attract the opponent and Sub Principles (how we could actually achieve the macro principle); Goalkeeper distribution, passing between the lines, playing direct and good positional play. Similarly, we have to do the same for all four moments and Set Plays. At least one of these four moments of the game or Set Plays should always be present in every training exercise. In general, when somebody watches your team’s game, he/she would be able to distinguish your philosophy; how you build up, your defending organization, and what is the team’s characteristics when you recover or lose the ball.

Next, it is essential to integrate moments of the game with fitness and tactical training. Primarily, fitness coaches have to be aware of a session’s tactical targets and perform their warm up and their part accordingly. For example, when the football target is building up, the fitness coach can design a warm up that would be connected with the building up objectives (video 2).

Video 2. Moments of the game – Offensive organisation warm up drill

Ideally, a fitness coach should be able to apply the team’s tactical patterns to the fitness part and also adjust spaces and players involved in the tactical training, according to the physiological demands of the day. Which is the best fitness training? Just play the game! Don’t overcomplicate things, just adjust the intensity and volume you want each day (with dimensions, restrictions, number of players). Mirror real situations in your drills, that players may face in the game, always with transition involved (always one more action after losing or recovering the ball). It is very important the exercises have continuity, with the players always able to think both offensively or defensively depending on the team in possession. When does the offensive transition start? Some coaches would say when we recover the ball, however, the answer is that we think offensively from the moment we start defending. Similarly, the defensive transition starts from the moment we start building up.

Working on transitions (offensive or defensive) is essential for players’ continuity in the game. Training tips are:

- Include transition elements in your fitness drills (video 3),

- incorporate both transitions (offensive or defensive) in the same football drill (video 4),

- use drills with specific actions and movements (e.g building up vs defending behaviors, third man moves, overlapping or underlapping) that you would like to appear more often and can be connected with your game model. (video 5).

Keep the players’ mind busy and help them understand the game first and then to build their fitness. Fitness training should always be complementary to tactical training. Don’t forget that.

Video 3. Moments of the game (Transitions – Physical)

Video 4. Moments of the game (Transitions – Football training)

Video 5. Moments of the game (Transitions – Game Model)

C) Integrated training & Periodisation

Understanding the team’s Game Model (and moments of the game), coaches must work on finding the ultimate balance between Physical, Technical and Tactical load. The big question is how a football coach and a fitness coach can integrate their work? Start with planning your meso-cycle and micro-cycle before designing any session. In general, fitness coaches should guide football coaches regarding session design using volume (total work), intensity (m/min), density (space/players involved) and recovery (drills, sessions).

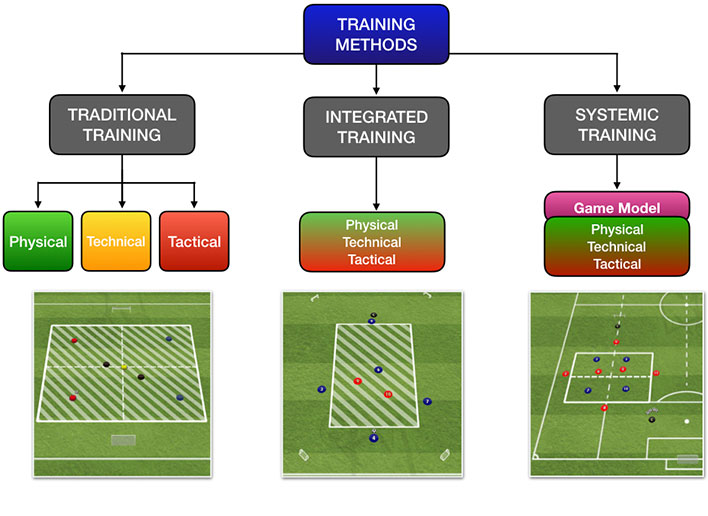

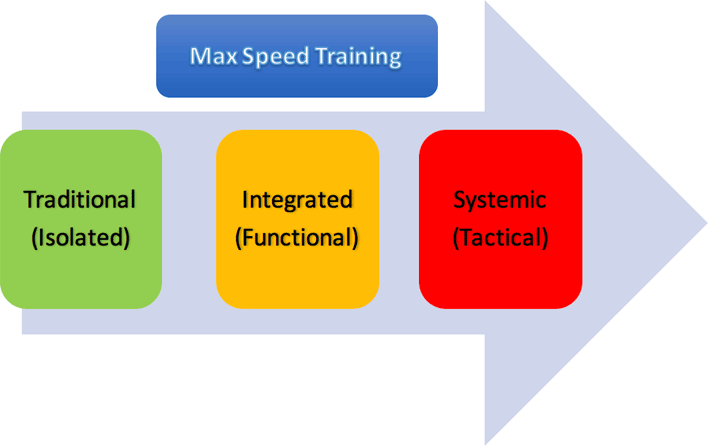

Looking at the training methods (figure 4) that can be used in our daily training process are:

- Traditional training, where the priority is the development of one target (physical, technical or tactical),

- Integrated training, where physical, technical and tactical targets are developed together and

- Systemic training (Tactical Periodization), where our Game Model is the reference when designing a drill or session.

Figure 4. Training Methods

Head coach and fitness coach have to align their daily targets and try to prioritize them within the session. For example, when the coach wants to work on defensive organization in small spaces, a fitness coach can use drills during warm up that focus on acceleration/deceleration and change of direction. In addition, the fitness coach can stress certain energy systems without the ball, according to the day’s target, preferably in the end of the session. Nowadays, with the use of live monitoring technology, we can see the players’ performance in real time and can top up any component we target.

Taking everything back to the beginning: What are the physical demands of a 90min game? If we try to monitor player performance at an elite level, we will find that a football player covers distances between 10-12km (depending from their position) with the majority of that being in low intensity (Di Salvo et al, 2010). Nonetheless, in the span of the distance covered, we have activities like tackles, headers, changes of direction and high intensity running of which Maximum Sprinting Speed (sprinting) constitutes 1-11% with 10-20 sprints (>25.2 km/h) (Di Salvo et al 2010; Haugen et al 2014). Let’s take the example of Maximum Sprinting Speed to see how can integrate both the physical and football part. Recent studies reported that before scoring 45% of their goals, the scoring player performed a sprint in high velocity (Fadue et al, 2012). Therefore, the ability of a football player to perform (repeatedly) that aforementioned 1-11% of the game is crucially important and may be decisive in a football game. Sprinting speed can be differentiated into acceleration (10m) and maximal sprinting speed or peak velocity (20-40m). Training wise, these two components should train independently as not all max accelerations lead to max speed (Haugen et al, 2014; Al Haddad et al, 2015). Training principles should definitely be applied (figure 5), from simple to more complex, progressive overload and so on.

Figure 5. Maximum Sprinting Speed training principles

Here, we add the traditional to tactical method, with exercises focusing on pure Max Sprinting Speed development (Physical) (video 6), exercises integrating basic movement skills with ball (Physical & Technical) (video 7) and exercises incorporating tactical movement patterns (Systemic) (video 8).

Video 6. Max Speed Training – a) Isolated (Traditional)

Video 7. Max Speed Training – b) Functional (Integrated)

Video 8. Max Speed Training – c) Tactical (Systemic)

In modern training planning, it does not make sense working in traditional blocks with different physical aspects (aerobic capacity – aerobic power – anaerobic capacity – anaerobic power etc). Big clubs spend 2-3 weeks in pre-season doing friendly games in different places around the world. After the first week (adaptation), according to the tactical periodization we can work all fitness components in relation to a) the team needs (tactical) and b) the level of complexity. Based on the tactical periodization (principle of horizontal alternation in specificity), we could work on football-specific training models, where physical terminologies like Strength, Endurance, Speed and Recovery describe the session’s targets. In this model, the priority is to achieve each day’s target with football, according to the team’s game model, avoiding a large amount of stress on the same physical component, providing the players with time to recover and reduce fatigue (Delgado & Mendez-Villanueva, 2018). The tactical target is changing according to our team’s needs or to our next opponent’s way of playing, but the physical target could remain the same on a given day (Delgado & Mendez-Villanueva, 2018).

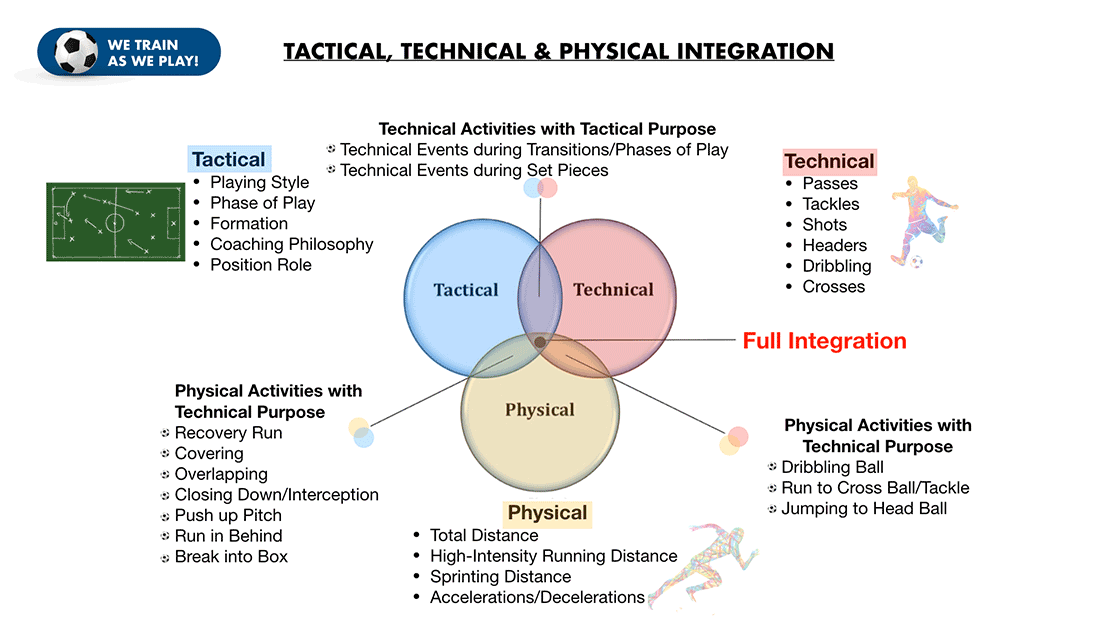

In another approach, in a recent study, Bradley & Ade (2018) have proposed an integrated approach (figure 6).

Figure 6. Tactical Technical and Physical Integration (Bradley & Ade 2018)

In this approach, the authors used ‘High Speed Running in relation to key tactical activities’ for each position as an example (eg: overlapping or underlapping of wide defender) and then collectively for the team (eg: high pressing). Therefore, instead of looking at the absolute value of High Speed Running (traditional approach), they used this physical parameter in relation with coach tactics in a more holistic way. According to the authors, understanding of the physical performance in relation to the tactical roles and instructions given to the players, will enable coaches to efficiently incorporate match metrics into the training process. In theory, this approach looks to be what we all “dreamed of”, however this still needs further investigation, since it is time consuming, requires well-trained staff and also needs expensive equipment (computerized tracking technology).

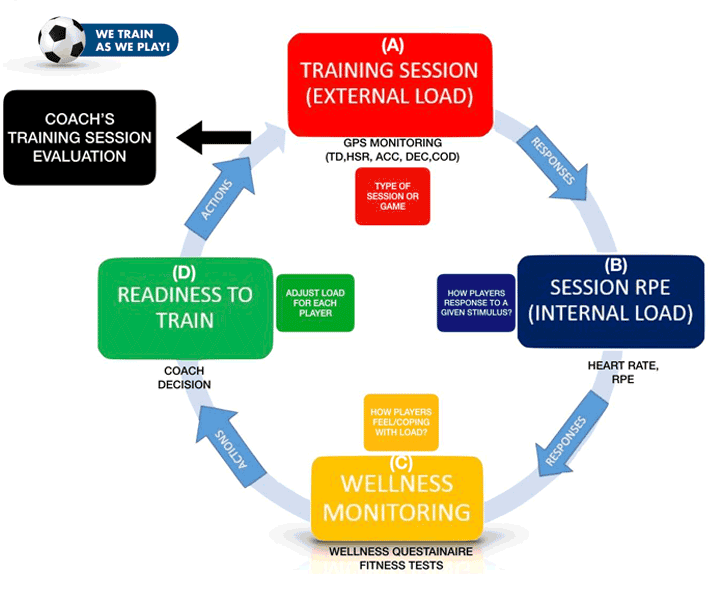

D) Monitoring (Training) cycle

It is essential for coaches to understand how total match or training load of physical/ tactical stimulus can affect players’ readiness to train or play. A group of top researchers (Gabett et al, 2017), recently published a helpful guide to all sport practitioners regarding the monitoring cycle and applied steps to make the training process much easier. In our modified monitoring cycle which effectively is the daily training cycle (figure 7), coaches have to understand how training stimulus can affect players’ readiness to train/play and to be ready to take decisions according to players’ needs. We have to be close to our players and be prepared to modify our plan according to their responses. In addition, looking at the monitoring cycle, it should be noted that the coach has to understand and feel what impact his session had on his players and if that was according to what he had initially planned or not!

Figure 7. Monitoring cycle (Adapted from Gabett et al, 2017)

STEP A

To begin the cycle with the first step, Match or Training load is frequently described in terms of external and internal load. External load refers to the specific training prescribed by coaches (type and content of a training session), which includes the external workloads of the player, such as distance covered, or number of efforts performed at different speeds (sum of physical & tactical load). This can accurately be measured with global positioning systems (GPS). Numerous studies have reported that Global positioning systems are acceptable system for measuring players’ locomotor activity when compared with a gold standard system like a laser gun (Varley et al, 2012; Roe et al, 2016). There are plenty of GPS systems in the market, from low cost to expensive. As sport practitioners, you have to make sure that you tested the validity and the reliability of your system. Only then, you will be able to have clean data and apply any coaching interventions.

STEP B

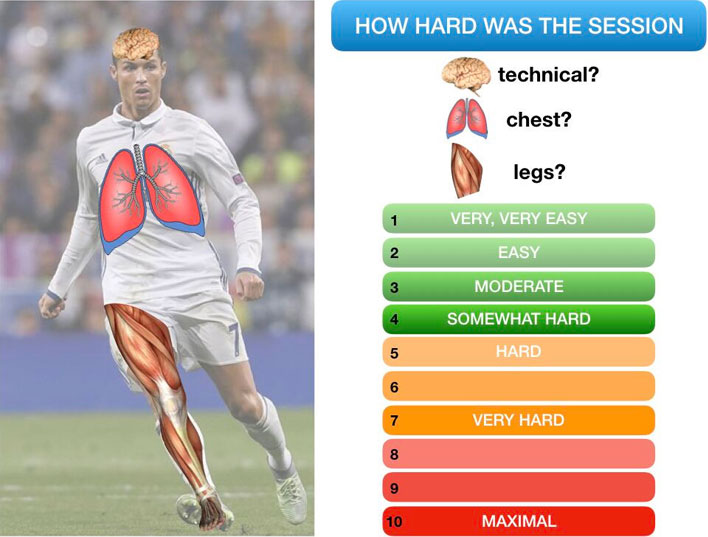

Moving on to the next step of the monitoring (training) cycle, to plan an effective training stimulus, coaches need to consider the players’ internal responses to a given external training load (Gaudino et al, 2015). The physiological strain resulting from the external training factors has been labelled the internal load (Viru & Viru, 2000). Thus, external training load is the training dose, and internal load is the players’ physiological responses to that training dose. As such, internal load elicits adaption to training (Malone et al, 2015). A combination of internal-external load monitoring, provides the most effective means through which to derive information regarding the players performance, fatigue and readiness to train or play (Malone et al, 2015; Bourdon et al, 2017). How can we measure Internal load? Heart rate monitoring is the most frequently used method across the last decade. Whilst heart rate monitoring is a valid method for monitoring training intensity in endurance sports, its validity is reduced in sports where the anaerobic energy systems are required (Impellizzeri et al, 2005). Session ratings of perceived exertion (sRPE) represent a simple and valid means through which to monitor internal load during activity comprising aerobic and anaerobic demands (Foster et al, 2001). Weston et al (2015), after reporting lack of sensitivity in sRPE, they proposed the differential ratings of perceived exertion (dRPE) which separate scores for breathlessness, leg muscle exertion and technical/cognitive exertion (figure 8). Separating players’ load perceptions to central and peripheral exertion can provide coaches with information that would help them to prescribe better training sessions. Lately, interesting practical findings using dRPE were reported showing 1) positional differences after a soccer match game (full backs had higher scores) and 2) increased cognitive exertion when played with teams at the top of ranking in the league (Barett et al, 2018).

Figure 8. Differential method of Ratings of Perceived Exertion

STEP 3

Next stop in the cycle is wellness monitoring. After understanding how external load impacts on players’ internal responses, it is time to measure players’ readiness for the next session/game. Monitoring fatigue and understanding players’ status can provide coaches with useful information that can help manipulating training load, reducing injuries and improving players’ performance. Jump protocols, heart rate variability, biochemical/hormones measurements, sub maximal running tests are just few of the tests used to monitor fatigue in professional football players, however the simplest and faster way is the athlete self-report measures (Thorpe et al, 2017). Asking your players how fatigued or sore they feel will provide you with all you want. Try to do the simple things well and efficiently instead of carrying out complicated and time-consuming practices that make your job difficult.

STEP 4

After analyzing the players’ wellness and status, the head coach is deciding who can fully train, perform a modified session or stay out of the session completely. The head coach is the one that has to filter all feedback from sport scientists, physios and doctors and act accordingly. This is a quick process and therefore information has to arrive to the coach as soon as possible before the next training session. It is essential how coaches interpret the wellness data. Fatigue or Sleep is up to head coach to decide if it is better for a player to rest or do a modified session. Soreness should be assessed by the physio or doctor before deciding anything. In that moment of the cycle, coaches can evaluate their work knowing if they have achieved their objectives or not. Consequently, having that feedback, they will be ready to modify and improve their work in future.

E) Training Session – Drill Design

Elite players do not necessarily require to be the fittest athletes but at least fit enough to cope with the demands of the match and execute their tactical role effectively (Lacome et al, 2017). Having that in mind, coaches should start designing their sessions and drills according to what the players will be required to do in the game. When preparing a drill or session, we should have a clear objective in our head for that particular session, week or cycle. There are 4 main objectives (figure 9) that we need to consider: a) Session comparison with the same week type, b) Session comparison with the same day type, c) what is the percentage compared with drill/session and d) Drill spaces used in the session. The target is different when having Small Sided games (SSG) or Long Sided Games (LSG). In smaller spaces, we focus mostly on tension with low number of players involved and as we are going to bigger spaces we focus more on duration or speed with a higher number of players involved. All are fitted nicely in the weekly plan with the principle of horizontal alternation in specificity where physical terminologies like Strength, Endurance, Speed and Recovery describe the session’s targets (figure 10)

Figure 9. Main Objectives when design a training session

Figure 10. Training session type

Furthermore, according to Tactical Periodization we split the specific principles of the game to different levels of complexity: a) Main principles of play: related to collective behaviors as a team, b) Sub-principles of play: related to inter-sectorial (between lines) and sectorial behaviors (defense-midfield-attack) and c) Sub-sub-principles of play: related to individual behaviors (individual player). Managing the complexity of the exercises performed through the week in relative maximum intensity, we aim to have the players as fresh as possible (Mendonca 2013). We can achieve that alternating a) between Principles and Sub-Principles of the Game, b) muscle contraction level (tension, duration, speed), c) Complexity level (low to high) and d) Spaces (small to large).

We need to remember that we have to create an environment in which physical, technical and tactical elements can be developed concurrently. Going deeper into the physical part and having averages/max from the game, we start building our sessions and drills. We should preferably train in a way to reflect the game’s intensity. Analyzing your games, you could identify strengths or weaknesses of your team that you could work in our training sessions. Try to go into the details, think out of the box and design drills and sessions that are helpful for you developing your game model and making your players understand it better (video 9).

Video 9. Design a drill from your Game Model

F) Worst case scenario

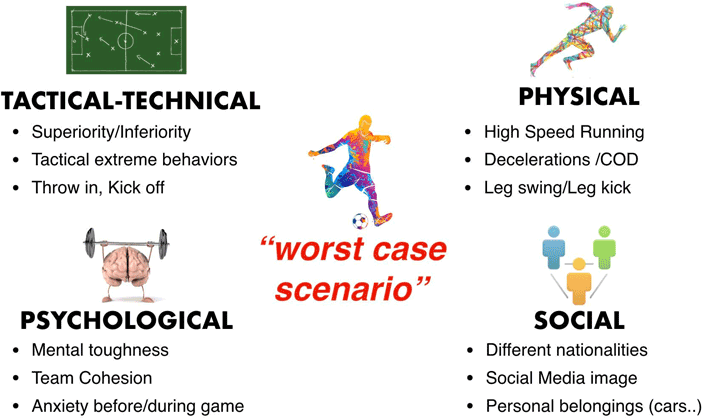

Details can make the difference! When competing at a high level, players should be ready for any given scenario: playing with less players (or more), winning (or losing), bad conditions and so on. It may be an extreme scenario of players having to run long distances or in high speed zones. Players should be trained to anticipate extreme behaviors or actions that they may face in a game. What should a coach do? Identify first which are these important “scenarios” for the team and train them accordingly. For instance, how many coaches work on throw ins? How many times did you see your team losing the ball from a throw in? What about a kick off? Have you ever trained a kick off? You have at least one kick off in the game. We could differentiate those actions in tactical-technical, physical, psychological and social. (figure 11).

Figure 11. Worst case scenario classification

1) Tactical: Football is the sport of uncertainty. You cannot predict what it will happen in the game, however you can train scenarios that can appear during the game. It all comes to the way we want our team to play and our Game Model. The players have to feel confident and fully prepared for any given scenario during the game; it could be training the kick-off or a throw-in, playing in superiority or inferiority in a specific areas and time. Football is a game of surprising the opponent, creating numerical superiority in certain actions and taking advantageous of that. Hence, we need to duplicate these situations in our drills. Then, with our tactical strategy we could provide our players with possible solutions to these situations, but we need to keep them involved in the whole process.

2) Physical: The game is becoming more intense with possibly less distance covered but more high intensity running required (Barnes et al, 2014). Tony Strudwich (ex Man Utd, Head of Performance,) in a recent presentation referred to “critical moments” as preparation for the most intense phase of their sport; 10m maximal burst (acceleration), high speed running (max speed) and train quick (speed of play). It is essential to make athletes hard to break, build resilience through volume and ensure athletes can cope with these demands. We need to first identify the physical peak demands of the game. There are 3 ways to do this: 1) Segmental; with pre-determined blocks (e.g. 5min periods), 2) Moving or Rolling Averages (we choose the periods from the raw data) and 3) Longest periods of ball in play (Whitehead et al, 2018). However, comparing all methods, the most appropriate method to use is Moving or Rolling averages as with Segmental we may underestimate the peak periods. Varley et al (2012), revealed much higher values using moving averages compared with segmental for 5 min peak periods of match play (177 ± 91m vs. 142 ± 24 m). Using rolling averages for a period of time (1-10min) and the match max values, we could have a reference for the players’ locomotor activities, which in turn will assist us in designing drills that will physically prepare players for any given scenario in the game.

3) Psychological: Lately, a lot of attention was given to this area. A lot of professional players are using sport psychologists to prepare themselves to perform better in the game. Wayne Rooney shared his visualization technique used to prepare himself for the game:

“I always like to picture the game the night before: I’ll ask the kitman what kit we’re wearing, so I can visualise it. It’s something I’ve always done, from when I was a young boy. It helps to train your mind to situations that might happen the following day. I think about it as I’m lying in bed. What will I do if the ball gets crossed in the box this way? What movement will I have to make to get on the end of it? Just different things that might make you one per cent sharper.”

Moreover, coaches are asking sports psychologists’ opinions before acting or taking decisions. We have to accept that this is another area that needs further investigation. For instance, mental toughness, which is acknowledged to be a crucial in football, coaches reported a relative lack of knowledge about how they can effectively develop this quality with their players (Cook et al, 2014). Jim Taylor has tried to help coaches and athletes prepare for the game with the 5 Ps:

Perspective – how important is the game for you?

Process – focus away from process and onto outcomes.

Present – focus on what you need to do to play your best right now, not think about the past or future.

Positive: think only positive, as negative thoughts can affect the present.

Progress – focus on yourself and the progress you’re making toward your goals.

4) Social: “Should I buy the new Mercedes or the new Ferrari?”

“Should I eat only rice or pasta? Cause I can afford buying meat”

Those are 2 different players’ questions. Regardless the country or the level you are at, you will always have different players’ status profiles, from rich to poor, from easy going to hard going and so on. Coaches should be aware of all the possible scenarios that appear in their teams and they have to manage accordingly each player. Moreover, social media’s exposure is an issue that can affect players’ status or even the relationship between them. Solomon Asch (1951) conducted a very interesting experiment to investigate the extent to which social pressure from a majority group could affect a person to conform (Youtube Video). Your teammates’ pressure of conforming to the group will make people act in the wrong way. Similarly, this can happen in any team or group of people. In a football team, having several nationalities and different players’ characteristics, you may have someone that can influence the group’s power and cohesion. It is difficult for some individuals to be deviant and may go with the group. It is our job as coaches, to protect our players and take actions before any unhappy situations.

References

- Akenhead R and Nassis G. Training Load and Player Monitoring in High-Level Football: Current Practice and Perceptions. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2016; 11: 587-593.

- Al Haddad H, Simpson B, Buchheit M, Di Salvo V and Mendez-Villanueva A. Peak Match Speed and Maximal Sprinting Speed in Youth Soccer Players: Effect of Age and Playing Position. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2015; 10: 888-896.

- Al Haddad H, Mendez-Villanueva A, Torreno N, Munguia-Izquierdo D & Suarez-Arrones L. Variability of GPS-derived running performance during of official matches in elite professional soccer players. Journal of Sports Med Physical Fitness. 2017.

- Barrett S, McLaren S, Spears I, Ward P & Weston M. The influence of playing position and contextual factors on soccer players’ match differential ratings of perceived exertion: a preliminary investigation. Sports (Basel), 2018; 6(13): 1-8.

- Barnes C, Archer DT, Hogg B, Bush M, Bradley PS. The evolution of physical and technical performance parameters in the English Premier League. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;35(13):1095–1100.

- Bradley P & Ade J. Are Current Physical Match Performance Metrics in Elite Soccer for Purpose or is the Adoption of an Integrated approach needed? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2018; 13: 656-664.

- Bourdon P, Cardinale, M, Murray A, Gastin P, Kellmann M, Varley M, Gabbett T, Coutts A, Burgess D, Gregson W & Cable T. Monitoring Athlete Training Loads: Consensus Statement. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2017; 12:161-170.

- Delaney J. How you should be using GPS, Part 1: Game Speed (2018). (online blog post). Gregson W, Drust B, Atkinson G and Di Salvo V. Match to Match Variability of High-Speed Activities in Premier League Soccer. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 2010; 31: 237-242

- Cook C, Crust L, Littlewood M, Nesti M, Allen-Collinson J. ‘What it takes’: perceptions of mental toughness and its development in an English Premier League Soccer Academy. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 2014; 1

- Di Salvo V, Baron R, Gonzalez-Haro C, Gormasz C, Pigozzi F and Bachl N. Sprinting analysis of elite soccer players during European Champions League and UEFA Cup matches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2010; 28(14) 1489-1494.

- Faude O, Koch T & Meyer T. Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2012; 30 (7): 625-631.

- Foster C, Florhaug JA, Franklin J, Gottschall L, Hrovatin LA., Parker S & Dodge, C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2001; 15(1), 109–115.

- Haugen T, Tonnessen, Leirstein S, Hem E & Seiler S. Not quite so fast: effect of training at 90% sprint speed on maximal and repeated-sprint ability in soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2014; 32 (20): 1979-1986.

- Impellizzeri, F. Rampinini E & Marcora S. Physiological assessment of aerobic training in soccer, Journal of Sport Sciences, 2005; 23(6): 583-592.

- Gabbet T, Nassis G, Oetter E, Pretorius J, Johnston N, Medina D, Rodas G, Myslinski T, Howells D, Beard A & Ryan A. The athlete monitoring cycle: a practical guide to interpreting and applying training monitoring data. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017; 51(20): 14521-1452.

- Gaudino P, Marcello F, Strudwick A, Hawkins R, Alberti G, Atkinson G & Gregson W. Factors Influencing Perception of Effort (Session Rating of Perceived Exertion) During Elite Soccer Training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2015; 10: 860-864.

- Gregson W, Drust B, Atkinson G and Di Salvo V. Match to Match Variability of High-Speed Activities in Premier League Soccer. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 2010; 31: 237-242.

- Juan Luis Delgado-Bordonau & Alberto Mendez-Villanueva (2012) Tactical Periodization: Mourinho’s best-kept secret? Soccer Journal May-June 2012 (28-34).

- Juan Luis Delgado-Bordonau & Alberto Mendez-Villanueva (2018) Tactical Periodization: A proven successful training model. SoccerTudor.com

- Lacome M, Simpson B, Cholley Y, Lampert P & Buchheit M. Small-Sided Games in elite soccer: Does one size ts all? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2017; 7:1-24.

- Malone J, Di Michele R, Morgans R, Burgess D, Morton J & Drust B. Seasonal Train-ing Load Quanti – cation in Elite English Premier League Soccer Players, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2015; 10: 489-497.

- Manzi, V., D’Ottavio, S., Impellizzeri, F. M., Chaouachi, A., Chamari, K., & Castagna, C. (2010). Pro le of weekly training load in elite male professional basketball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 5(24), 1399–1406.

- Mendonca P. (2013). Tactical Periodization, a practical application for the game model of the FC Bayern Munich of Jupp Heynckes (ebook).

- Rein R & Memmert D. Big data and tactical analysis in elite soccer: future challenges and opportunities for sports science. Springer Plus, 2016; 5: 1410.

- Roe G, Darrall-Jones J, Black C, Shaw W, Till K & Jones B. validity of 10-Hz GPS and Timing gates for assessing maximum velocity in professional rugby union players. International Journal of sports Physiology and Performance, 2017; 12(6) 836-839.

- Taylor J. Train Your Mind for Athletic Success: Mental Preparation to Achieve Your Sports Goals. 2017, e-book.

- Thorpe R, Atkinson G, Drust B & Gregson W. Monitoring fatigue status in elite team-sport athletes: Implications for practice. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2017; 12, S2-27-S2-34.

- Sarmento H, Marcelino R, Anguera T, Campanico J, Matos N & Leitao J. Match Analysis in football: a systematic review. Journal of Sport Sciences, 2014; 32 (20): 1831-1843.

- Varley M. Fairweather I & Aughey R. Validity and reliability of GPS for measuring instantaneous velocity during acceleration, deceleration and constant motion. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2012; 30(2): 121-127.

- Varley M, Elias G & Aughey R. Current match analysis techniques’ underestimation of intense periods of high-velocity running. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2012; 7: 183-185.

- Viru, A., & Viru, M. (2000). Nature of training effects. In W. E. Garret & D. Kirkendall (Eds.), Exercise and sport science (pp. 67– 95). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Weston M, Siegler J, Bahnert A, McBrien J & Lovell R. The application of differential ratings of perceived exertion to Australian football league matches. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2015; 18: 704-708.

- Weston M. Training Load monitoring in elite English soccer: a comparison of practices and perceptions between coaches and practitioners. Journal of Science and Medicine in Football, 2018; 2 (3): 2160-224.

- Whitehead S, Till K, Weaving D & Jones B. The use of micro technology to quantify the peak match demands of the football codes: a systematic review. Journal of Sports Medicine, 2018.

Responses