Strength Training Manual: Planning – Part 4

1. Introduction

2. Agile Periodization and Philosophy of Training

3. Exercises – Part 1 | Part 2

4. Prescription – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

5. Planning – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

I am very happy to announce that I am finishing the Strength Training Manual. I decided to publish chapters here on Complementary Training as blog posts for two reasons. First, I want to give members early access to the material. And second, this way I can gain feedback and correct it if needed before publishing it.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Enjoy reading!

Decoupling Progressive Overload from Adaptation

Progressive overload is one of the building principles of strength training. In simple terms, progressive overload represents the need to make training dose higher and higher1 as one becomes stronger and stronger. This is needed to stimulate further adaptation and improvements in performance. However, as I have explained in the previous chapter, training dose is a very complex construct, which makes progressive overload a complex construct as well. From simpler “forum for action” perspective, progressive overload is needed to push the adaptation.

But that is only one perspective of the progressive overload. Another one is to actually adapt your training to the adaptation experienced. In other words, adaptation pulls progressive overload thresholds up. As you adapt, you will have to do more (take a new training dose) to progressively overload2. These are the exact complementary pairs introduced in the “push the ceiling vs. pull the floor” model in the previous chapter. Progressive overload and Adaptation are embraced into a complex dance of interdependence (Figure 5.35), where progression moves the adaptation, while adaptation affords progression. It is complex circular causation (see Figure 5.16 for a circular model of dose -> response of which Figure 5.35 is simplification).

Figure 5.35. Progressive overload and Adaptation are embraced into a complex dance of interdependence

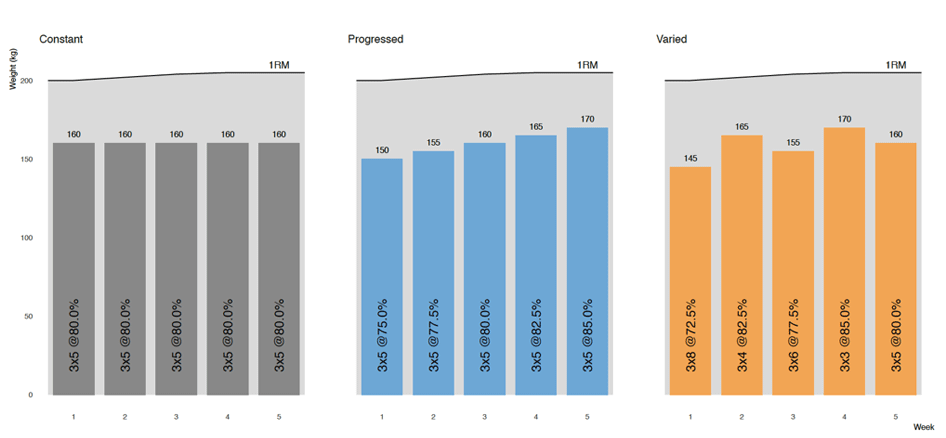

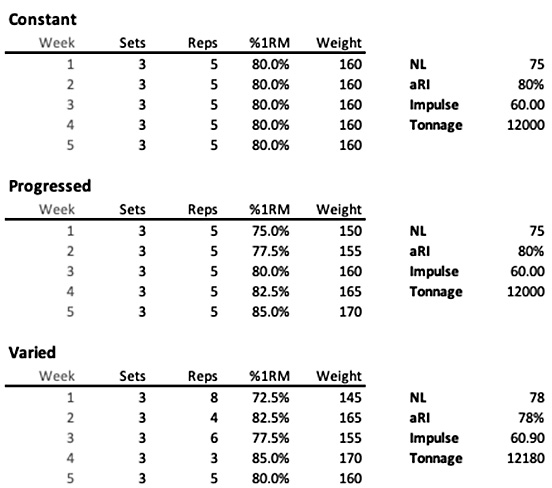

Unfortunately, this complex dance between progressive overload and adaptation is often bastardized and reduced to changes in week to week set and rep schemes. Figure 3.35 represents hypothetical example where the same adaptation is seen with three different scenarios. In this hypothetical example, adaptation is represented by 1RM in the back squat, while the training dose is represented by two back squat workouts a week, done for five weeks. Initial back squat 1RM in this hypothetical example is 200kg, and changes to 205kg across 5 weeks. To plan the loads using percent based-approach, initial 1RM of 200kg is used. The adaptation pattern is same across three scenarios.

Figure 5.36. Adaptation and progression needs to be decoupled. See text for explanation

Constant scenario involves performing the same workouts (3×5 with 160kg) across five weeks. Might be questionable if these workouts would be the same (and thus represent the same dose, but we need to stick with this “Small World” model), since improvements across weeks (and these improvements might be beyond simple 1RM, and might involve other improvements beyond this example, like work capacity, explosiveness and so forth) might afford one to perform reps faster, with greater depth or with shorter rest between sets.

Progressed scenario involves performing 3×5 workout, but with progressively heavier weight, starting from 3×5 @75% (150kg) in week one, and reaching 3×5 @85% (170kg) in week five. Assuming 1RM stays the same (which is not the case, but for the sake of argument let consider that scenario), every week involves increase in the exertion level (expressed as RIR), cause by using heavier load for the same number of reps. Since “bastardized” concept of progressive overload is implemented in this scenario, this is believed to drive the adaptation and thus represents a must element in strength training programs. This “progression” can mean different things as will be explained in a few paragraphs.

Varied scenario involves performing three sets of different reps (8, 4, 6, 3, 5 reps), but since each set is done at the same exertion level (same RIR, at least in theory for this hypothetical example), there is no “progression” across weeks, even if there is an undulating change in weight used (145, 160, 155, 170, 165kg).

If we look at some dose metrics in the Table 5.13, we can see that all three scenarios created very similar, if not the same, training dose. Same training dose (given these metrics) equals same training response (at least in this hypothetical example, where response is change in the squat 1RM).

Table 5.13. Dose metrics for the constant, progressed and varied scenarios.

This hypothetical example hopefully demonstrated that progressive overload is a more complex topic than simply increasing or varying weights across weeks. Progressive overload happens over a longer time frame than few weeks.

From the aforementioned example it might seem that (week) progression and variation are useless concepts or noise. This cannot be further from the truth. Although constant scenario produces the same adaptation, this approach might be boring as hell, might increase the likelihood of chronic overload syndrome and might suffer from a lack of variability. But some athletes might prefer this one. Some coaches actually use this approach to estimate the adaptation curves and try to predict their peak and shape which can help in planning the peak (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007, 2010). And as said previously, non-varying the pre-planned load might not mean the manifested performance is not varied or progressed.

The progressed scenario might be too predictable (“Oh crap, I barely survived this workout, and for the next I need to add extra 2.5kg”) and if brought too far forward, might be really ‘pushing’ the adaptation and cause downside rather than upside. Some athletes prefer this type of planning, where steps are known and pre-planned ahead and they can feel the increase in weight (“Oh, I can see the progression from the last workout and I like the feeling”).

When it comes to varied scenario, some might actually prefer it due it variability and a lack of predictability (i.e., would be harder to judge progression when reps change, as opposed when reps stay the same and athlete can clearly see things going up, or down). This strategy can also help in reducing the likelihood of suffering from boredom and chronic overload syndrome due its waves in load (but I am speculating).

The point of this is that, after the basic dose and progressive overload across a longer time frame, which are necessary conditions, one can experiment with progressions and variations based on individual preferences, but also complex interactions with other training elements. We do not know how given variations and progressions affect adaptation for a given individual and when interacting with other training components, so these needs to be experimented with.

It is important to notice that all the aforementioned scenarios can belong in the push and pull domains (see Figure 5.23).

Progression vs Variation

In the West, the key word in strength planning is “progression.” In the East, it is “variability.”

Although progressive overload represents increasing the training dose to push the adaptation and/or is being pulled by the adaptation itself in the long run, what is the difference between progression and variation in the short term3?

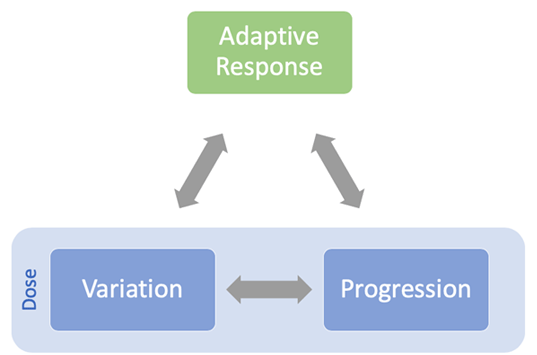

It is very hard to distinguish between progression and variation, but it is important to realize that both of these complementary aspects are involved in planning and represent component of the training dose (both progression and variation are necessary stimuli) (Figure 5.37).

Figure 5.37. Variation and Progression are hardly distinguishable but necessary components of the dose construct.

Roughly speaking, progression is increase in difficulty or toughness (see classification of the set and rep schemes based on toughness in Table 5.12 ), while variation represent, well variation, within the same level of difficulty (or it might represent pursuit of a different objective or quality). On the flip side, one can look at progression as a particular form of variation.

Having said that, let’s figure out if 1×5 @85% (Intensive) compared to 5×5 @75% (Extensive) represents a progression or variation? It could be said that it represents progression since higher %1RM is used in the intensive version, but it could also mean that the extensive variant is progression since it represents more NL. Since both use 5 reps can we assume it is variation at hand here? Tricky situation.

What about 3×10 @65% (Hypertrophy objective) compared to 3×5 @80% (Strength objective)? Is this an example of progression or variation? 3×10 can be much more displeasurable (particularly if you are a powerlifter considering everything over 3 reps cardio), thus moving from 3×10 to 3×5 might be considered regression. Using %1RM, moving from 3×10 to 3×5 might be considered progression, since more load is utilized.

As you can conclude yourself, it is hard to distinguish between the two. I am not sure the distinction is that important in practice, truth to be told. That is why I prefer to approach this problem from “forum for action” perspective, which I like to refer to as vertical and horizontal planning.

Vertical and Horizontal planning

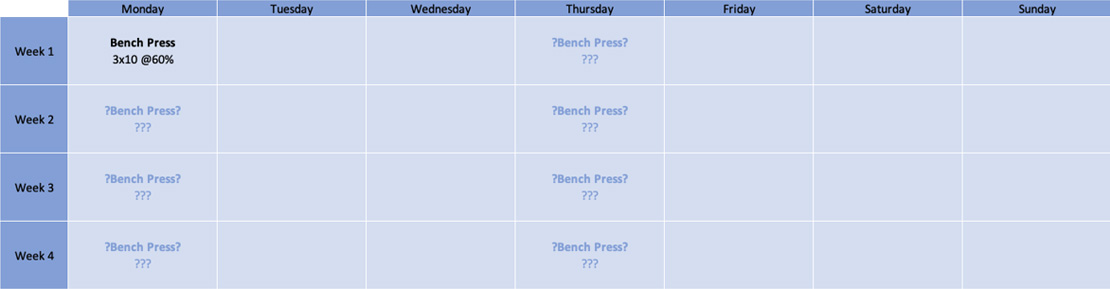

Let’s assume you have two days a week (bottom-up approach) to train the bench press (or upper body horizontal pushing movement): Monday and Thursday. For the sake of example, let’s assume that the Monday workout is bench press 3×10 @60% (Table 5.14).

Table 5.14. Two days a week to train the bench press. The question is how to plan?

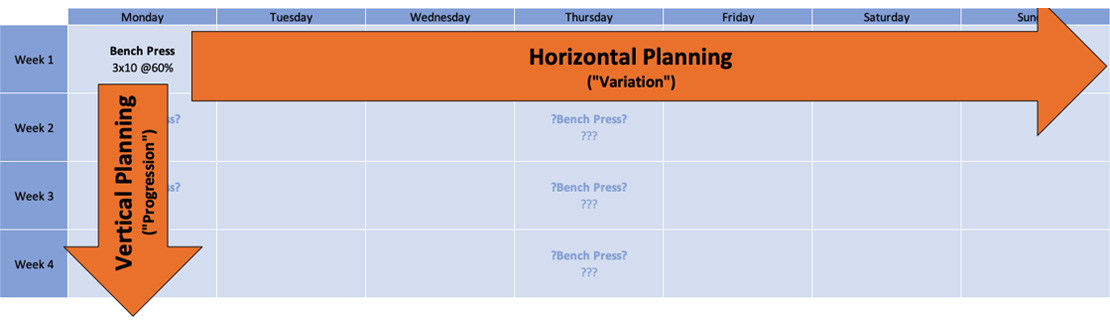

The question is how to vary this workout on Thursday, and how to progress both of them across weeks? As already explained, this progress vs. variation is very tricky, so it is better to refer to this problem as horizontal and vertical planning (Table 5.15). Horizontal planning is more leaning towards variation, while vertical planning is leaning more towards progression. This doesn’t need to be the case all the time, but a general rule (and might be easier to grasp the concept of horizontal and vertical planning) that can be, and usually is, broken.

Table 5.15. Horizontal and vertical planning

Horizontal planning

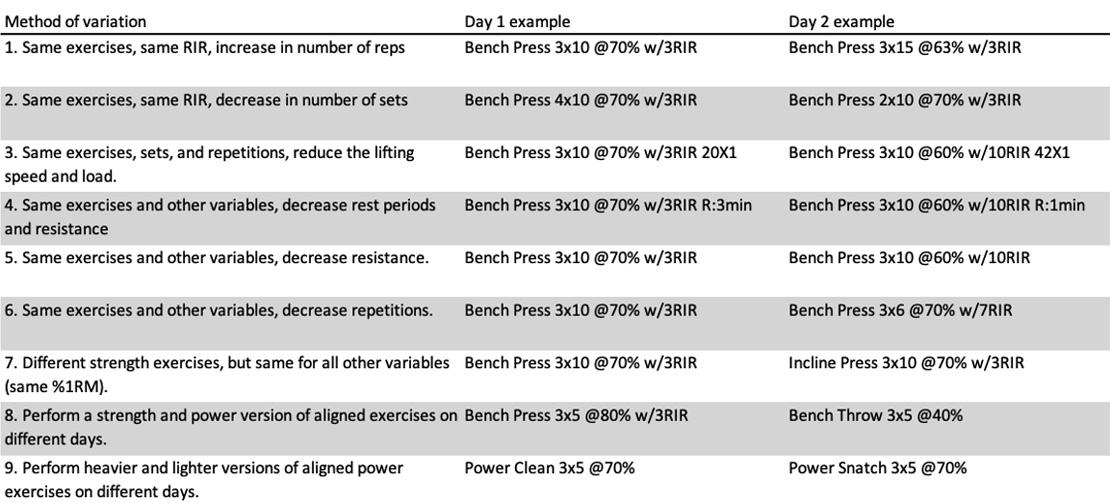

Horizontal planning, usually represents varying a workout that is within the same progression stage (although, as will be seen in a few paragraphs, doesn’t need to be the case). Dan Baker (Baker, 2007) provided an example table of variations that could be utilized when two similar workouts are performed in one week (Table 5.16)

Table 5.16. Few examples of altering training workout within a week. Reproduced with permission by Dan Baker (Baker, 2007)

Similar to categorizations of set and rep schemes, each of these workouts can utilize different objectives, prescriptiveness, volume, toughness (this would be considered a progression) and methodology.

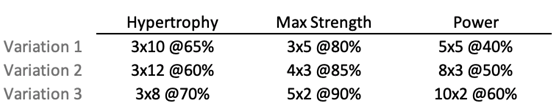

For the sake of example, let’s assume we are performing squatting pattern three times per week, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and we aim to hit Hypertrophy (Armor Building), Max Strength (Anaconda Strength) and Power (Arrow) utilizing the following variations of set and rep schemes (Table 5.17)

Table 5.17. Variations of set and rep schemes for three different objectives

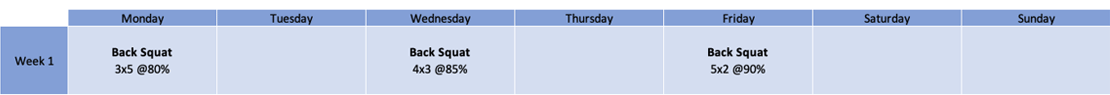

The first strategy might be to use variations of set and rep schemes from the same bucket (objective), in this case maximal strength (Table 5.18):

Table 5.18. Varying set and rep schemes horizontally within the same quality bucket is often called Daily Undulating Programming (DUPr)

Since this strategy “hits” the same objective (in this case maximal strength), this horizontal planning strategy is usually called Daily Undulating Programming or DUPr.

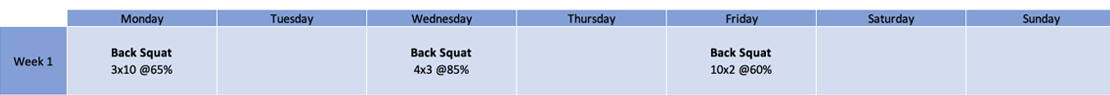

In the next strategy, we might opt for hitting different buckets (objectives) in every training session (Table 5.19).

Table 5.19. Varying set and rep schemes horizontally between different quality buckets is often called Daily Undulating Periodization (DUPe)

In this case we are aiming at different objectives, hence the name for this horizontal planning strategy is Daily Undulating Periodization or DUPe. The coaches and authors usually don’t make a distinction between these two types of Daily Undulating programs/periodizations (they use DUP acronym for both), but it is important to realize that there is a big difference.

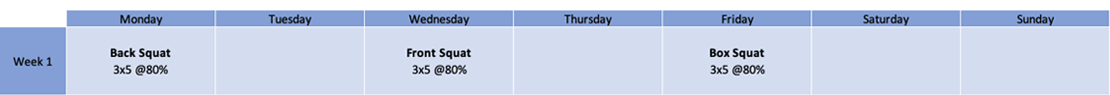

Now imagine rather than repeating the back squat, we use a different variation of the movement (either an exercise that is specific to the squat if you are a powerlifter or strength specialist, or exercise that is within the same movement pattern if you are strength generalist) (Table 5.20).

Table 5.20. Same movement pattern – different exercises

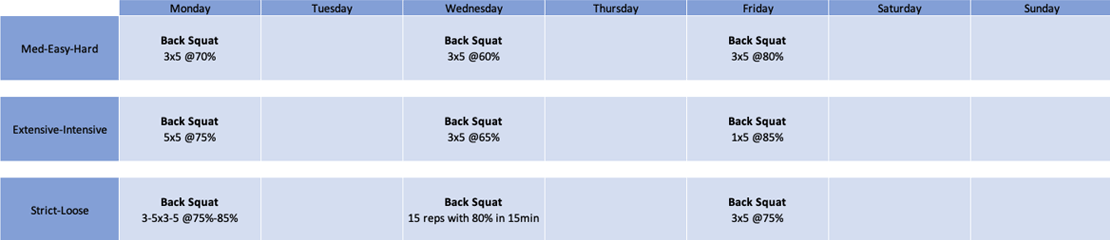

The combinatorics don’t end there – all other categories of set and rep schemes can be utilized in the horizontal planning (Table 5.21).

Table 5.21. All categories of set and rep schemes can be utilized in the horizontal planning, like extensive – intensive (volume), toughness (medium-easy-hard, although this represents progression), prescriptiveness (strict – loose)

Of course, there is nothing wrong with repeating the exact same workout on all three days. As outlined in the previous chapter, some coaches have a particular ideology regarding how horizontal planning should be done for novice, intermediate and advanced athletes. Here, I am only pointing out the combinatorics, heuristics and complementary aspects of planning. It is up to you how you are going to implement it. I personally, don’t believe anymore that there is a particular long-term ideology one needs to follow through career. Horizontal (and vertical) planning thus provides a very flexible framework that you can use to analyze different training programs and when planning your own programs.

Similarly to the slot planning (see Figure 3.23 in Chapter 3), depending on which component of the prescription unit (see Figure 5.26) is varied, one can come up with the following quadrant (Figure 5.38).

Responses