Systemizing and Planning the Warm-Up

Introduction

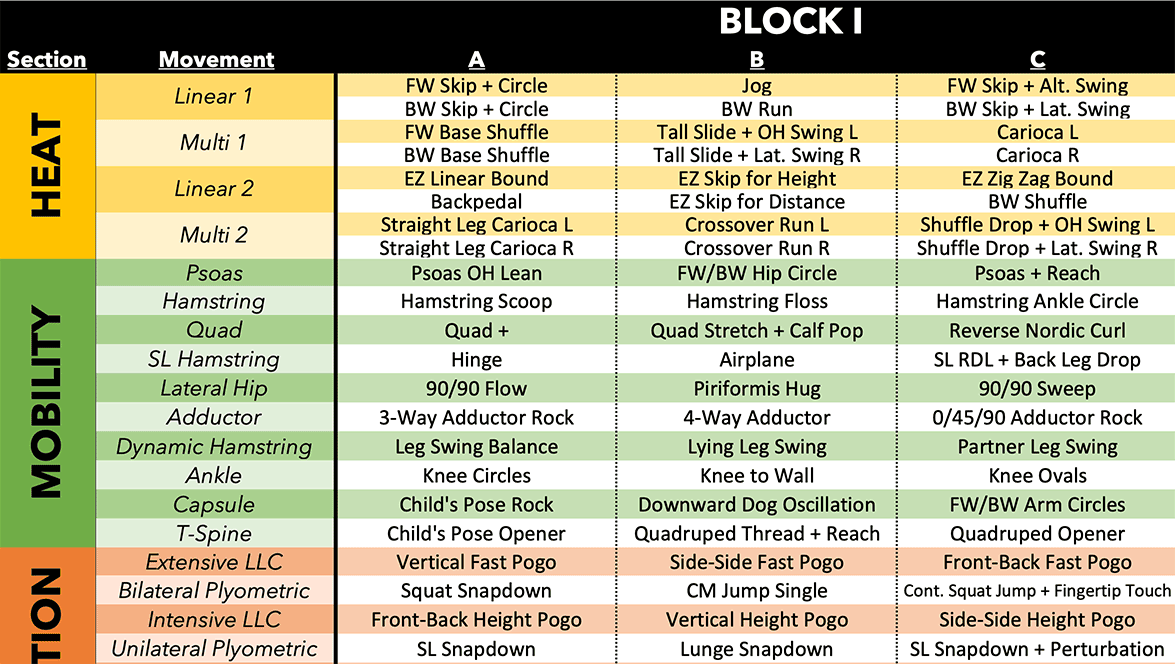

No matter the time of year, whether you won or lost, off-season or in-season, there is one consistency in athletics throughout it all: the warm-up. As Ryan Horn points out below in this viral social media post, by his estimates, a college basketball team will spend an average of ~56 hours warming up over the course of a year. No matter how you adjust those numbers to better reflect the sport you work with and the level you work at, the point remains intact; you spend an awfully large amount of time warming up. To throw away this time in the interests of just ticking the box to say a warm-up was completed reductively because they are sweaty and breathing hard, doing the same warm-up every single day, or in favor of a pseudo-militaristic warm-up designed to make the strength coach look good while everyone claps in unison to static stretch, is to do your athletes a disservice in not maximizing opportunities to enhance athletic development, especially when considered in the macro view of how much time such a portion of your preparatory sessions demands over the course of a year.

(credit: Ryan Horn)

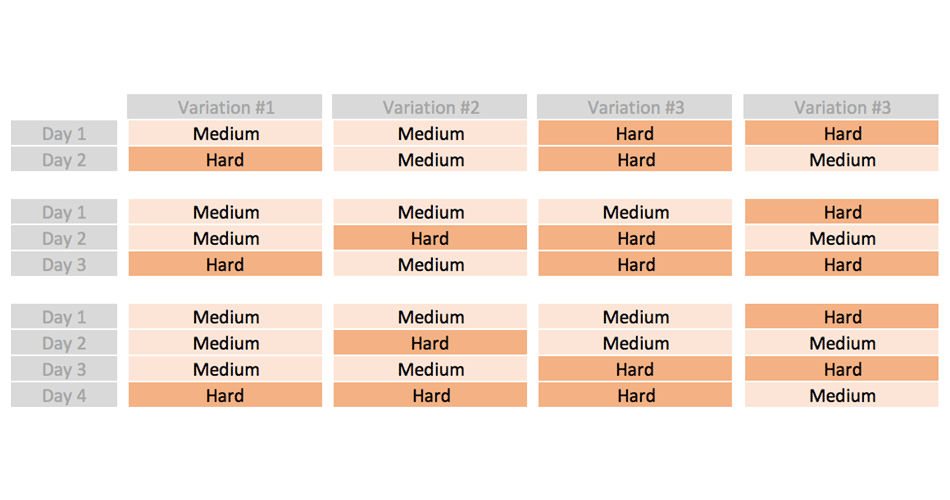

The reality is warm-ups, like any other element of a holistic sport preparatory plan, can be systemized and periodized, and should be given this degree of reverence, given how much time is inherently allocated towards this segment of preparatory sessions. The convenient aspect of warm-up periodization is that unlike other elements of physical preparation such as on-field or gym-based elements of training, which are subject to constant iteration and review as new information about the athletes and the way they are adapting to stressors is presented, your warm-ups can be designed and planned during a down period in the year, and not require much, if any, revisitation throughout the year, so focus can be directed towards the more intensive aspects of your team’s preparation that require closer attention. It merely becomes a matter of printing off the next progression of your warm-up whenever you decide to progress to that next block of warm-ups.

Goals

Succinctly, warm-ups should serve as the seamless pathway from a state of inactivity into the preparatory session ahead, be it a sport or physical preparation session. Along that pathway, however, are opportunities for addressing numerous developmental goals, including:

- Largely, “being a better human” (borrowed from Cory Schlesinger)

- Movement literacy/proficiency

- General work capacity

- Joint/tissue mobility

- Gymnastics/tumbling exposures

- Combat prep

- Balance/proprioception

- Biomotor skill rehearsal/mechanical drilling

- Perception-action coupling

- Ultimately, specific preparation for the demands of the session ahead

Another worthwhile goal I seek to accomplish in designing warm-ups comes from my first and most formative mentor named Mike Niklos, who impressed upon me the value of utilizing warm-ups to introduce upcoming movements/concepts in a lower intensity/complexity manner to prepare athletes for what is ahead. An example of this ideology could be that if you are planning to utilize fluctuators (such as varied arm positions) during speed training in an upcoming phase of physical preparation, you could use your Prime segment in the current phase to expose athletes to your sprint mechanics drills utilizing these fluctuators, so athletes are given the opportunity to explore these fluctuators and reinforce desirable attractor states in a lower demand task prior to arriving at the higher demand task of sprinting in the next phase. Alternatively, if there is a plan to progress from single effort plyometrics to repeated effort ones from the current phase to the next, athletes could utilize extensive repeated effort jumps in the current phase’s activation segment of the warm-up to serve as a submaximal “dress rehearsal” of the task that will eventually be completed at maximal intensity.

It is worth bearing in mind that sport does not happen in a tidy, neat fashion; rather, it is chaotic, with athletes put in precarious positions under unpredictable forces, awkward landings and movements, falls, and everything else in-between, all while trying to accomplish sporting tasks that lead to winning. Beyond all of the previously outlined developmental opportunities, warm-ups provide space for athletes to progressively explore this chaos, such as learning how to fight for position against another human doing the same, learning how to land after receiving a shove in mid-air of a jump, exposing athletes to extreme ranges of motion under a load of their own body weight from various crawling patterns, or just learning how to roll and fluidly coil their bodies and elongate the deceleration of their mass as it interacts with the ground during a fall so as to avoid blunt trauma that could occur as a result of a fall into the ground void of any sort of tumbling maneuver (see the video below).

Sport is chaotic; this athlete who gets stick checked and loses possession of the ball does a very subliminally athletic maneuver as she loses footing, as she log rolls with the momentum of her body to elongate her deceleration into the ground, finds a prone position from which it is far more efficient and advantageous to get back upright and get back into the game incredibly quickly. This athlete had the benefit of both a highly successful professional athlete parent, varied sporting background, and an immensely high work ethic and intent toward her preparation that cannot be ignored as possible contributing factors as to why she was able to navigate this chaotic moment so seamlessly, as compared to other athletes who might’ve just landed on their back and taken much longer to get back into the game while incurring a much more impactful blunt trauma to the posterior structures.

The point should loom large; the 10-20 minutes that you are afforded to get your athletes ready for the upcoming session carries the opportunity for continued athletic development, even during times of the year when concentrated physical preparation is at a premium due to competitive demands. Whether it is equipping your athletes with various mobility drills that they might be enticed to utilize on their own, reinforcing rudimentary movement principles, or providing opportunities for athletes to learn how to navigate the chaos of sport, there are many goals that can be accomplished. Congruent to the way by which program design is approached, consideration should be given to the biodynamic and biomotor demands of the sport you work with, i.e. it is probably not as prudent to keep a thread of top-end speed mechanics drills in your warm-ups year-round for a tennis program, as it might be to keep acceleration or change of direction mechanics drills in year-round, nor would it be worthwhile to do any sort of combat/collision prep, seeing as tennis never engages in close proximity with their opponent. Just as rehab exists along the same spectrum as training, warm-ups exist along the same spectrum as sports preparation, just as a much lower demand segment of their preparation, so apply the same basic principles of training to your warm-up design and don’t overthink it. Beyond those principles, these general progression principles are good to bear in mind as you are mapping out future phases of your warm-up:

- Slow → Fast

- Extensive → Intensive

- Simple → Complex

- Isolated → Integrated

- Closed → Open

Overview

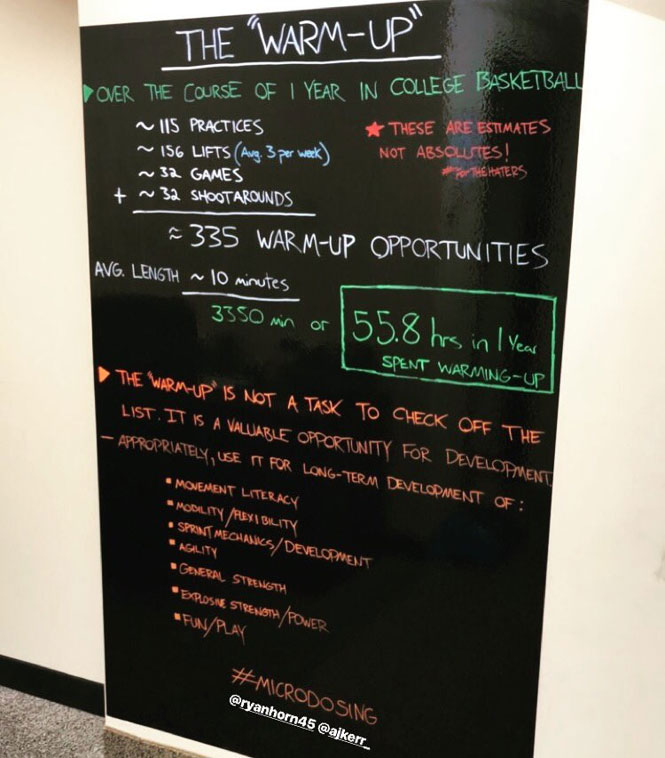

The warm-up structure I utilize templates classic RAMP protocols from Dr. Ian Jeffreys. RAMP stands for:

- Raise

- Activate

- Mobilize

- Potentiate

With a slightly different nomenclature, but similar goals, the structure that I utilize follows as such:

- Heat

- Mobility

- Activation

- Prime

Anecdotally, I think it makes much more sense to mobilize initially after tissues are warmed, and then begin activation drills before funneling towards the planned session via the Priming drills chosen to precede the session, but this is a small, inconsequential detail should you be more keen to following the RAMP protocol precisely.

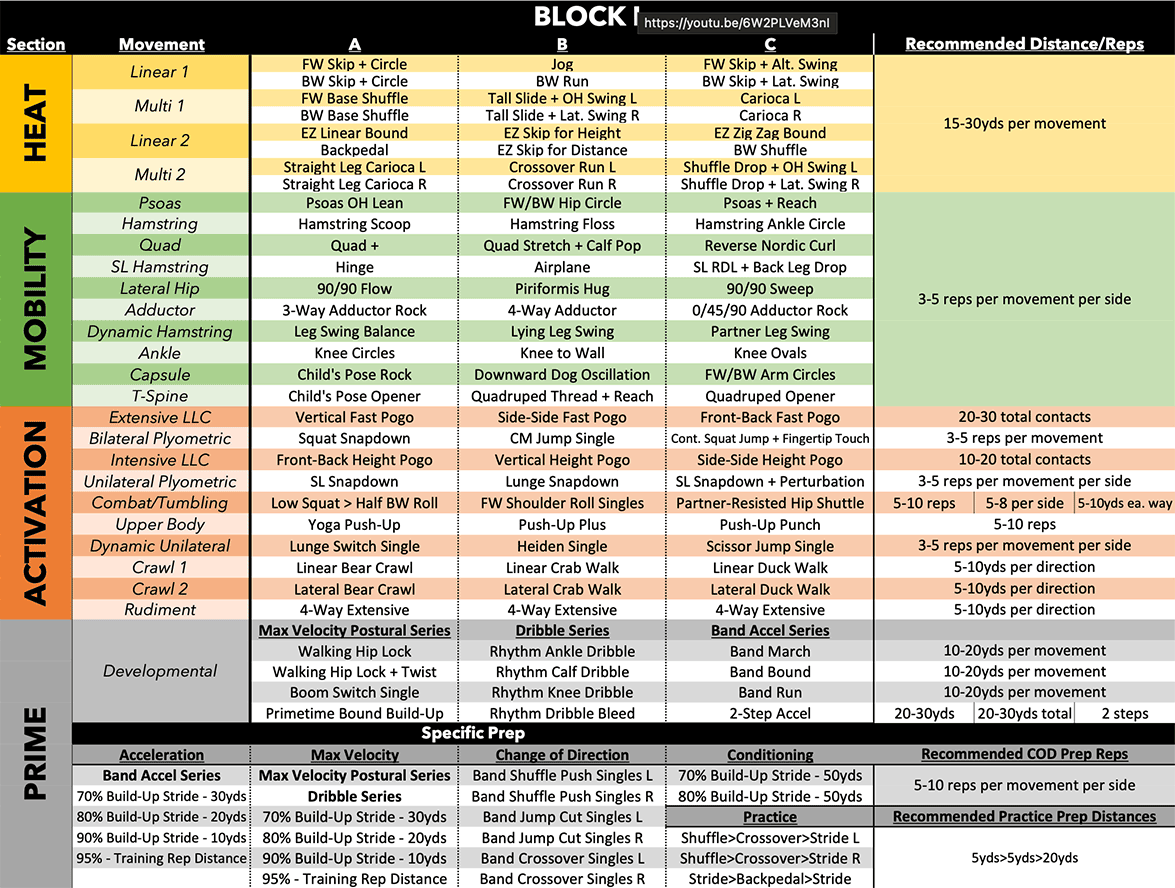

The second column of the sheet serves just an organizational purpose for planning future blocks and also allowing me to make sure I am ticking all of the boxes I want to tick within that segment of the warm-up. There will be small adjustments to that column, again based on the sport, so the combat section would be taken out for non-combative sports, as an example. In general, I aim to apply the 1/N heuristic approach towards each phase of the warm-up and address all major joints, muscle groups, planes, and variations across the entire week, all while deploying the most foundational variations possible during Activation and Prime phases that allow for progression towards more complex and intense variations of those movements (following progression principles as outlined at the end of the previous section). You can certainly take concepts from this article and apply them to designing more specific warm-ups for athletes with very specific competitive demands such as pitchers or quarterbacks, and it would be quite interesting to me to see the resulting warm-ups that those who work with specific demand athletes like that design, so please reach out and share them with me should you decide to go that route.

Offseason warm-ups will most likely need to look different from in-season warm-ups, which will need to look different from competition warm-ups- you will probably be afforded less time during the in-season, not to mention you are probably not attempting to tick any developmental goals during a competition warm-up, so much as you are making sure that the athletes are building into maximal sporting movements. The convenient aspect of this structure is that you can very easily hide/remove rows from your master template to fit the sport you are working with and the time of year.

Regarding in-season warm-ups, you will want to give consideration to the amount of time you are afforded, and the gaps that the sport leaves in their development and preservation of physical qualities. As an example, sports with denser competition segments might not leave much room for max velocity exposures, so keeping in max velocity technical drills such as Hip Locks, Hip Lock + Twists, and the Dribble Series might serve your athletes well in grooving desirable attractor states of max velocity sprinting until opportunities for speed top-ups are presented.

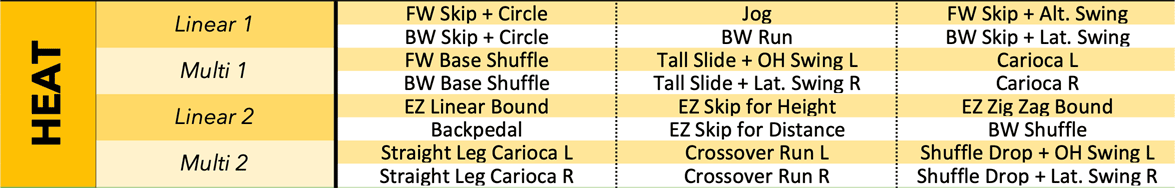

Heat

Goal: Increase body temperature, respiration/heart rate, joint viscosity, and blood flow to working tissues

This segment can be completed while moving or stationary, depending on the session ahead, logistics, space, and the variety of other elements that can constrain your warm-up. You might find yourself surprised at the variety of movement patterns that athletes may struggle to complete with fluidity and ease initially, so this is very much a section for “becoming a better human” and learning how to do a variety of multi-planar movements, skips, bounds, shuffles, crossover gaits and anything else you can think of. To add progressions to this section, consider having athletes alter their center of mass, so maybe they could go from a tall base shuffle to a short base shuffle with hips dropped. You could also add small perceptive elements, such as a very low demand/output mirror component, and then layer in more perceptual complexity by having the entire group go together, so now in addition to just perceiving their teammate, they also have to be attuned to the environment around them. I have included examples of such progressions you could work through below.

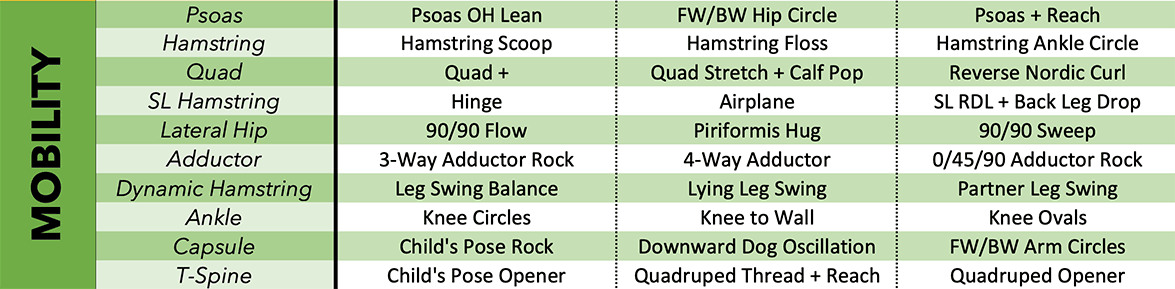

Mobility

Goal: Increase working range of motion of joints and tissues

Once tissues have been warmed, and joint viscosity increased, I find it to be logical to move next into mobilizing tissues and joints prior to beginning Activation movements that serve as the segue to Prime segment and ultimately, the actual session. This segment of the warm-up is pretty straightforward to me, and I do not believe warrants much in the way of progression. Perhaps incorporation and/or progression into movement flow or FRC concepts, or the use of external modalities such as a bands for joint distractions could represent avenues for progression, but logistically working this into a field-based session may prove difficult and cumbersome.

Dependent on your goals, you can take a more 1/N approach to this segment and touch a little bit of everything, or if you are going for a more specified warm-up as alluded to previously, be a little bit more targeted towards key areas that warrant mobilization for the demands of the task ahead.

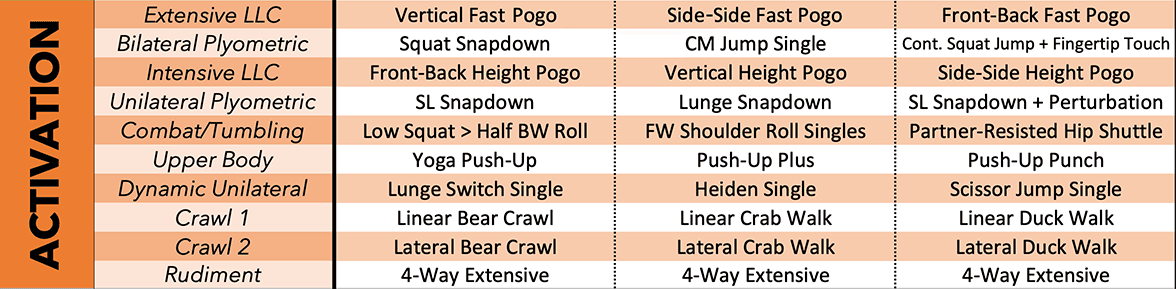

Activation

Goal: Increase neural drive to working tissues

Now through the first half of the warm-up, efforts should begin to turn towards funneling a seamless transition into the session and the high intensity actions accompanying it. While still removed from the final segment of the warm-up, there is also an opportunity in this segment to address a vast array of developmental areas, with consideration given to: plyometrics, lower leg conditioning, grappling/combat, tumbling, gymnastics, crawling, isometric holds, balance/proprioception, and prehabilitative exercises. There are a lot of boxes that can be ticked throughout this segment, coupled with the logistical and time restraints of completing a warm-up, it will be necessary to decide which areas can and should be addressed within this segment, and which ones can be placed in other areas of the program if deemed to be important enough. Also bearing in mind that this section, in particular, can represent an opportunity to introduce upcoming movements in a lower intensity/complexity manner, so with enough deliberate planning, your warm-ups can coincide with your training progressions and facilitate a “grooving” of the movement before the movement is deployed as a training means.

I tend to take this section to prepare athletes for explosive actions, provide daily exposures to fundamental patterns such as rudimentary foot contacts, loading/sequencing of jumping, combat/collision prep such as grappling or jumps with perturbations and then introduce progressions to these fundamentals such as heightened execution intensities, greater complexity such as more degrees of freedom, the use of fluctuators, or increased integration of movements, or chaos such as perturbations or other open partner-based interactions. I have included a few videos of how I progress through several movements that I often include within this section below.

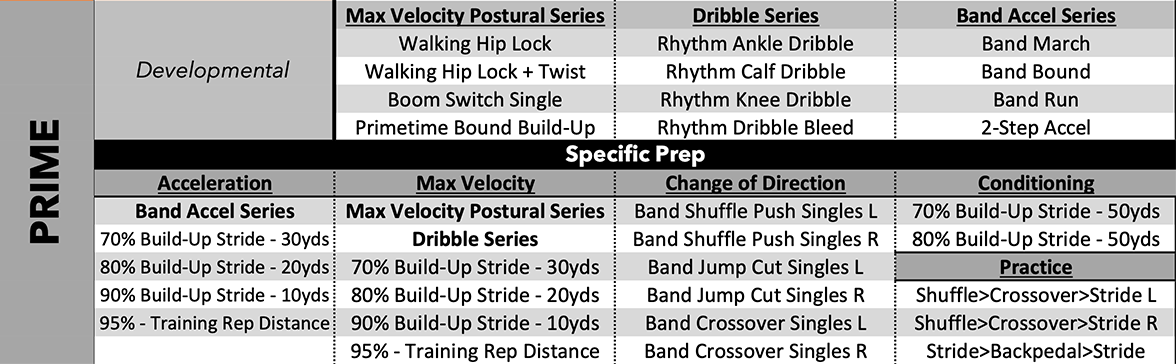

Prime

Goal: Seamless physical transition into the upcoming session

As previously discussed, dependent on the time of year, you can look to tick developmental boxes that leave more to be desired by the sport itself, or you deem to be critical enough to afford your athletes more exposures to those qualities in the offseason. Should you elect to take this route, I would recommend placing these elements earlier in this segment, as the movements you conclude the warm-up with should bear close resemblance to the demands of the upcoming session.

As you’ll see, I keep a section of this segment that are my developmental boxes that rotate in rhythm with my three warm-ups, and then have a separate section that depending on the session ahead, I will transition into the appropriate category of drills to create that natural segue into the session. My larger looming goal is that by the time the warm-up is finished, the athlete should be able to go out and instantly jump into the first practice period/training drill and execute at full speed and not feel a need to continue building into the session. It escapes me who said it (if it was you, please leave a comment or drop me a message so I can properly credit you), but the end of the warm-up and the start of the session should be indistinguishable from each other. Below I have included some examples of the progressions your athletes could go through for the Hip Lock drill for upright sprinting, and a shuffle progression for multi-planar movement.

Conclusion

In case the introductory paragraph didn’t make it clear, given the consistent presence of warm-ups within the sport, this aspect of your program should get more than a passing glance. Feel free to pull from this framework and the movements listed as you see fit for your situation, or use your creativity to create your own progressions, using basic training and progression principles that have been outlined earlier in the article. Warm-ups are not just an exercise in box-ticking; they are a valuable opportunity for athletic development and to introduce some fun into a segment of preparation that is generally stale and unchanging.

If you want to purchase a 4-block warm-up template that includes 4 levels of progressions, video demonstration links, and recommendations for distances and repetitions of each movement, please feel free to head to this link below to pick up a copy that you can begin utilizing in your work with your athletes.

Responses