Strength Training Manual: Exercises – Part 1

1. Introduction

2. Agile Periodization and Philosophy of Training

3. Exercises – Part 1 | Part 2

4. Prescription – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

5. Planning – Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

I am very happy to announce that I am finishing the Strength Training Manual. I decided to publish chapters here on Complementary Training as blog posts for two reasons. First, I want to give members early access to the material. And second, this way I can gain feedback and correct it if needed before publishing it.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Enjoy reading!

What is the point of exercise classification? To impress girls with differentiating between exercises for the long and short head of the biceps muscle? To pass the biomechanics class exam?

None of this, of course. The purpose of classification is not to create a place of things, but a forum for action. Creating categories from place of things perspective always comes with two issues. The first one is that creating more than needed precision with categories represents an exercise in futility and a rabbit hole (e.g., why have categories of exercises for long vs. short biceps head if you do not plan using them somehow?). There are always unlimited ways to classify exercises, depending on what criteria is being used. Besides, these criteria will be usually in some type of conflict (later in the chapter you will see a few of those in the figures). The second issue is that because there is a category, you will have a proclivity to use it in planning when there is no practical significance in doing so. For example, having vertical and horizontal press category will create more proclivity do designate training slots for them, but they might not need special treatment (for example with strength generalists, like team sport athletes).

The goal of exercise classification is thus to help you in planning and to simplify complexity (i.e., Small World model) and to direct your decision making. It bears repeating that categories are artificial, and that border is fuzzy rather than either/or, which means that some exercises can belong to multiple groups (e.g., is split squat single leg or double leg movement?), and exercises from a particular group can differ (e.g., step-ups vs lateral lunges – one is vertical and the other is lateral, although both are single-leg movement). It also bears repeating Jordan B. Peterson: “Categories are constructed in relationship to their functional significance”. This means that categorization will depend on the potential use, particularly if you work with strength specialists (e.g., powerlifters, strongman, weightlifters, and heavy athletics like a shot put) or strength generalists (e.g., everyone else that uses resistance training to help in achieving performance in something else, like team sports athletes, combat athletes or what have you).

General vs. Specific

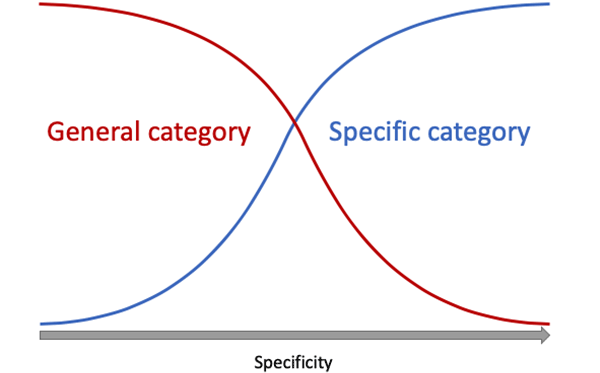

Strength specialists might prefer to utilize classification based on specificity or how similar particular exercises are to competitive exercises. For example, powerlifter might classify exercises using their similarity to competitive bench press, squat, and deadlift. One common approach (Small World, or mental model) that implements this idea is a simple classification to general exercises and specific exercises (see Figure 3.1):

Figure 3.1.

Exercise classification based on specificity into general and specific. Note the fuzzy border between groups, rather than either/or distinction.

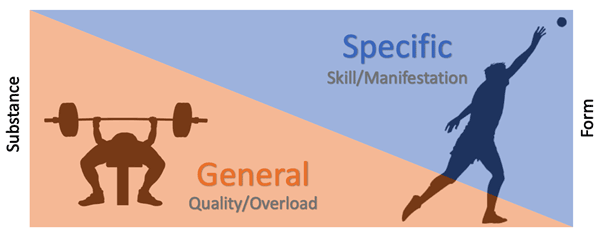

According to Grand Unified Theory (GUT; see the previous chapter) model, general exercises usually develop some innate (latent) quality (substance) by providing an overload, and specific exercises express that potential (form) through skill development and manifestation (see Figure 3.2). This dichotomous thinking (either/or: either you overload with general mean or you transform with specific, or develop vs. express dichotomy) is quite common, although not many coaches are aware of using it. For example, improve VO2max (potential) and your running performance in the game will improve, or in a shot put improve your strength using bench press and transform it by doing a shot put.

Figure 3.2.

Substance and Form of the Grand Unified Theory applied to general versus specific exercises.

Keep in mind that this is also a Small World model and that different camps utilize this model (or other models) differently. For example, a shot putter (who we might consider strength specialist in this case) might use incline bench press to improve the potential and utilize shot putting to manifest (or transform) that potential. This apparent dichotomy of ability versus skills (or substance and form) is being used in some schools (to my knowledge in American T&F schools) while being critiqued in others (for example in Bondarchuk’s approach to hammer throwing (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007, 2010)). Another example might be the use of specialized exercises in Westside powerlifting (Simmons, 2007) to target specific quality or weak links (i.e., potential), which will be later converted to competitive performance using the most specific lifts (i.e., form). In contrary, Sheiko powerlifting school (Sheiko, 2018) might approach things differently (using a different Small World model) by being less dichotomous and treat specific lifts (bench press, squat and deadlift) as developmental and skill dependent, rather than just a sole manifestation of underlying potential that is being developed with specialized exercises. Again, these are all Small World representations, and as we all know, both schools of powerlifting are more than successful in developing world-class lifters. An example from soccer might involve arguing with the head coach who says: “Players never squat in a game” (referring to form), while you try to convey that they do need to strength train to improve underlying potential or substance (to improve performance on the pitch, but also to protect from the Downside, i.e., injuries).

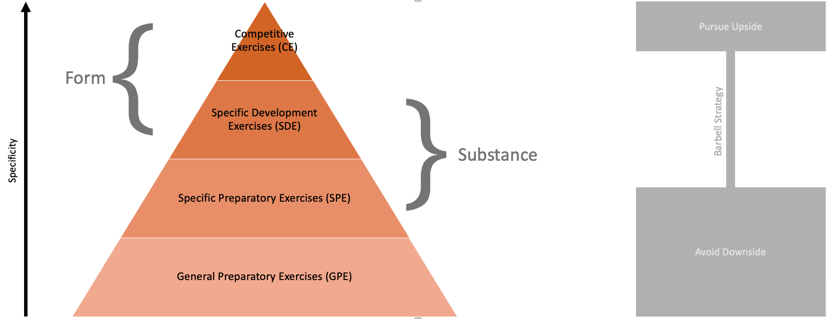

Extension of this model (by including additional categories in general vs. specific continuum) is the model by Dr. Anatoly Bondarchuk (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007, 2010) which is quite famous and utilized in track and field circles (see Figure 3.3)

Figure 3.3.

Exercise classification based on the work of Dr. Anatoly Bondarchuk (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007, 2010) and its relationship to the barbell strategy.

In addition to GUT’s substance-form complementary pair, utilization of CE and SDE exercises can be considered investing in the Upside (improving performance), while utilization of the SPE and particularly GE exercises can be regarded as protection from the Downside (making sure you don’t fuck yourself up with too specific work). For a powerlifter, this might mean doing some stability work, stretching, or horizontal and vertical pulling (should we call it Vanilla training – see the previous chapter) or some aerobic conditioning or bodyweight strength circuits (to improve Mongoose Persistence?; also see the previous chapter) which can all help in protecting from the Downside.

I have personally used Bondarchuk categories in my work and previous writings, and I believe they are a beneficial mental model. I have used them to help me categorize speed, power, and other strength and conditioning components, and I will continue to use them as a tool in the toolbox (i.e., multi-model thinker), particularly for strength specialists (or athletes that compete in cm/kg/sec sports). The dealbreaker issue I have with this model is that its categories depend on what we use to judging specificity. The categories of exercises might be very different for a powerlifter, as opposed to a rugby player. Take into account that specificity and hence exercises categorization for a rugby player which involves sprinting, acceleration, jump, ruck, maul, shoulder tackling and so forth. That being said, it is hard to pinpoint the exact category of an exercise in complex team sports (i.e., strength generalists). After all, most if not all strength exercises for team sport athlete will be in the GPE and SPE category. In that way, although very useful as a general viewpoint, Bondarchuk categorization is not very useful (lower functional significance) in team sports or for strength generalists. For this reason, I will utilize few different categorizations that I have found to have the biggest forum for action, which will guide my decision making and help me to decide what are the big buckets (or planning slots) that I have to take care of. The following categorization models are mostly aimed at strength generalists, although they can be utilized for strength specialists, potentially as sub-categories of the SPE and GE categories in the Bondarchuk categorization model.

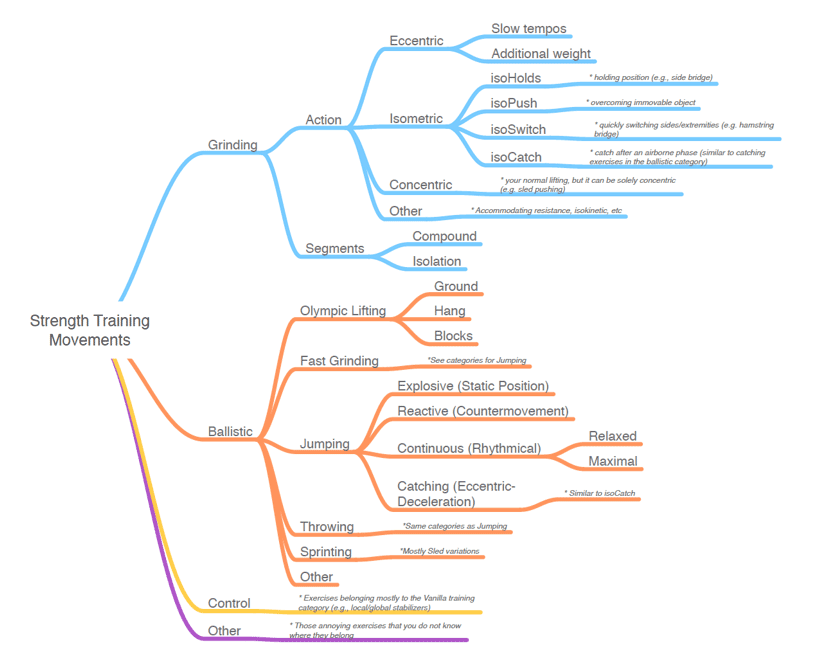

Grinding vs. Ballistic

Grinding movements are slow, controlled, compound movements (e.g., squats, deadlift, bench press) with constant tension, while Ballistic movements are fast and explosive (e.g., jump squats, hang cleans) with a burst of tension followed by relaxation, and they usually involve a flight of the body or the implement (e.g., barbell or a medicine ball). Additional categories involve Control movements (mostly for Vanilla Training, e.g., local and global stabilizers, but also has a lot similarity with complex movements category later in the chapter which demands symmetry and stabilization) and Other (that annoying category for exercises you do not know where they belong to). As with any categorization, it is hard to draw a fine line between categories since there are some similarities between them. Here, Figure 3.4 illustrates one possible classification of the movements. Please keep in mind that there are numerous ways to classify and enter the rabbit hole – I have included only the categories that I think have the most forum for action when working with strength generalists.

Figure 3.4. Categorization of movements based on their type.

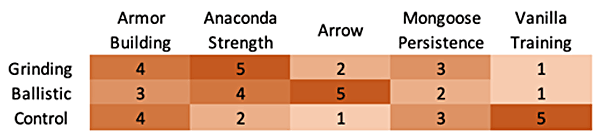

Figure 3.5 contains the hypothetical (and very simplified) relationship between Grinding, Ballistic, and Control towards developing Anaconda Strength, Armor Building, Arrow, Vanilla Training and Mongoose Persistence qualities.

Figure 3.5. What qualities development are grinding, ballistic and control movements good for.

The higher the number is, the better fit it is. Keep in mind that this is just a speculative highly simplified model.

Grinding movements

Figure 3.4 contains the additional classification of the grinding movements based on muscle action and the number of segments involved. Using muscle action, we can classify grinding movements to predominantly (1) eccentric, (2) isometric, (3) concentric, and (4) other 1.

Eccentric category usually involves an emphasis on slow lowering phase (eccentric phase) or somehow adding extra weight on the lowering part (e.g., leg press with two legs, lower with one).

Isometric category involves categories by my colleague Alex Natera (see Figure 3.4 for details). IsoHold can also belong to Control movements, while isoCatch is very similar, if not the same with catch exercises in the ballistic category.

The Concentric category is your regular lifting movements, although specific apparatus can be used only to perform movements concentrically (e.g., heavy sled pushes and pulls).

Other category involves, well everything else, from accommodating resistance to using EMS (Electric Muscle Stimulation).

When it comes to the number of segments involved, the simplest classification involves isolated movements (e.g., chest flies, biceps curls) and compound movements (e.g., bench press, pull-ups).

Ballistic movements

Figure 3.4 contains additional classification of the grinding movements to (1) Olympic lifting, (2) Fast Grinding (think of dynamic effort squats or bench press with 50-60% 1RM), (3) Jumping, (4) Throwing, (5) Sprinting (mostly heavy sled towing/pushing exercises), and of course the (6) Other category.

Olympic lifting is further classified based on the starting positions: (1) ground, (2) hang, or (3) blocks. Additional classification might involve catching position (e.g., full, power, muscle), but that would be an overkill for this simple big picture overview.

Additional subcategories for fast grinding, jumping and throwing are categories based on the action, and they involve (1) explosive from a static position (e.g., think of squat jumps from pause), (2) reactive (e.g., counter-movement jump or depth jump), (3) continuous (e.g. rhythmical jump squats that can be all-out, or sub-maximal rhythmical), and (4) catching oriented (e.g., jump and land). We can probably add other categories here as well, pick up every other variation that one might use for jumping, throwing and fast grinding movements (e.g., combining grinding movement with ballistic in a contrast super-set or what have you).

Control movements

Control movements category is a bloody mess, and involves everything from core stuff, to BOSU ball and breathing fuckarounditis. Vanilla Training mostly utilizes these movements with the aim of mostly protecting from the Downside.

Simple vs. Complex

What can be put on top of grinding and ballistic classification (one can include control category here, but I will leave it out to simplify 2) are simple versus complex movements. This way we get a quadrant: on the x-axis, we have movement time (a long time for grinding movements, and short time for ballistic movements), and on the y-axis, we have complexity axis (from lower complexity to higher complexity). I like to refer to this model as Time-Complexity quadrants (TCQ) (See Figure 3.6).

Responses