Running-Based Conditioning for Team Sports – Part 2

Click here to read Running-Based Conditioning for Team Sports – Part 1 »

Principle #5: Training Transfer

I have touched upon training transfer in the discussion of work capacity. Transfer is defined as: if I improve in doing X how much will I improve in doing Y? Or in plain English: if I improve my squat strength, how much my 10m run will improve? These two qualities could be skills or motor abilities.

We tend to see higher ‘transfer’ between the exercises that look similar (if you improve vertical press, there is a more transfer to improve bench than squat), but on the flip side there are not a lot of studies on transfer mostly because it is hard to control it. We tend to see cross-sectional studies (throwers who throw X1-X2 tend to have bench press of Y1-Y2, and throwers who throw X2-X3 tend to have bench press Y1-Y2, or vertical jumpers of 30-40inches tend to have squat of 1,5-2,0BW), but they don’t provide any proof of causation: if I improve/change one aspect how much other aspect will improve/change in longitudinal way. Besides, no one is only training vertical press to see improvements in squat 5 weeks later, so it is hard to isolate training transfer from the training noise.

Training transfer tend to be positive, negative or neutral. Positive means that if you improve certain quality you tend to improve another related one. Negative mean that if you improve certain quality you tend to decrease another related one. And neutral transfer means there is no transfer. All this sounds great in theory and it is very nice intuitive concept, but I am still not familiar with sound studies on it using longitudinal approach. The ideas mostly come from the trenches of great coaches, like Anatoly Bondarchuk.

Another thing coaches tend to forget about training transfer is Production vs. Production Capacity. Thus they tend to over-emphasize ‘specific’ activities that look like movements in their sport for the sake of higher transfer (e.g. squats vs. single leg squats on balance board). But we also have Production Capacity transfer – if we perform activities that are not related to the competition activity, yet they tend to reduce injuries and increase availability of the players during the season, I would consider this transfer as well.

For the above reasons coaches tend to favor specific drills, but as we have seen they tend to have problems with specificity vs. overload principle and as we are going to see with specific chronic load syndrome.Besides they forget about transfer to Production Capacity as well.

If you want to learn more about this I suggest you also check the video by Joel Jamieson.

As with develop vs. express problem, training transfer tend to be a dynamic animal as well. For example, improving squat from 1,0 to 1,5xBW will increase your vertical jump in good degree. Improving it further from 1,5-2,0 will tend to improve it as well, but slightly less. Improving the squat from 2,0 to 2,5 will yield some benefits but they are going to be smaller and smaller, while the work that needs to be done is increasing as well the injury potential. This can be said for anything else from hammer throwing to soccer.

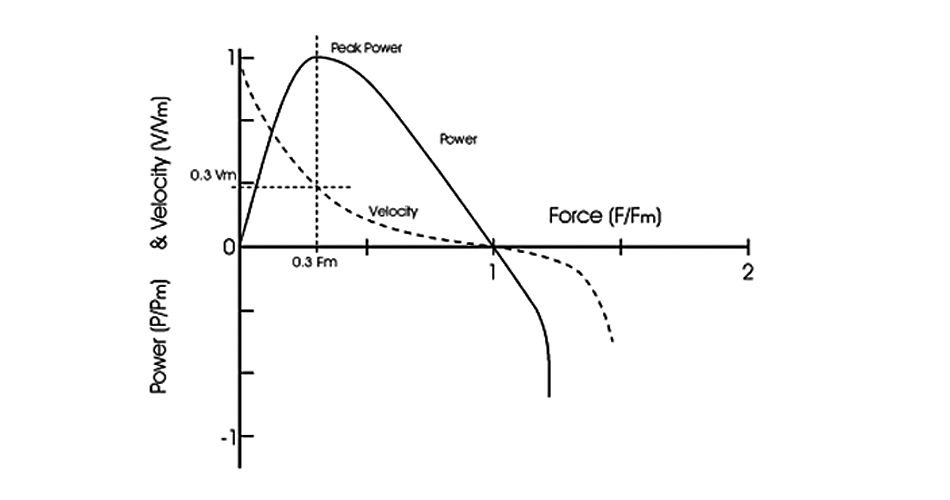

We tend to ask questions when is one too strong or possess too much endurance? This is the problem of transfer. With soccer for example, improving you endurance (MAS, VO2max, LT, etc) will yield improvements in game related parameters along with improvements in work capacity. But there is a tipping point where the transfer is neutral and becomes negative. This negative transfer might not be ‘direct’ per se, but rather the process of improving endurance to highest levels tend to distract you from the training that have bigger importance to you as a soccer player.

Same thing with strength training. Up to a certain point, squat strength improvements has great transfer to improvements in acceleration and jumping ability (Production), along with making you less injury prone (Production Capacity). This transfer tends to get smaller and smaller and building up more strength tend to demand more and more time and energy and end up distracting the players from more important training. Dan Baker talked about this as well in this PAPER from 2001.

The problem is identifying this tipping point, and the coaches tend to the ditch the whole strength thing because they tend to see things in black and white. Things like – if weightlifting makes better football players, let’s recruit weightlifters, or even worse – if weightlifting improves football, then football improves weightlifting, which comes back to develop vs. express discussion.

Going back to the soccer example and training transfer of endurance training. Since this is the dynamic process it is important to identify whether there is some potential for transfer of endurance training (running based conditioning) to game related performance and work capacity (as far as I know there is only one longitudinal study that involved mentioned hypothesis – a study done by Martin Buchheit et al. which I explained in the following post on RSA). And this is the tricky part. It might involve some experimenting and monitoring the effects. In my opinion, the running based conditioning is mostly suited for intermediate guys.

Let me explain. With kids and beginners there is no need to (specifically) improve capacities since they don’t have the skill to exploit it yet (see Verkhoshansky graph in part 1).

With highly advanced guys their capacities are (tend to be) very high (for their sport/position) and their skill to use them is very efficient (although there might be players who are more efficient in using what they have, and ones that are less efficient in using what they have, but they have better potential – training them might be different).

Improving their capacities might involve too intense training or too much volume that might yield no further benefit in terms of improvement of game related performance and that might make them too tired and drained. With these guys the key is to make them able to play year round without injuries and allowing them and the clubs to make God-knows how much billions $$$.

Even with those characteristic some things can still be improved. The problem is that their competition calendar (problem of context) is so dense that it is hard to improve anything in terms of physical quality to a higher degree. Strength and conditioning coaches that work with highest level clubs (especially soccer), and with the exception of the few, actually don’t do much serious physical preparation work – mostly prehab/rehab stuff, monitoring, warm-up, cool-downs, recovery sessions and everything else low intensity and low volume.

Sometimes the exceptions are off-season, pre-season and bench guys. But this depends on the sport, where soccer is the most notorious for such an example. If you are interested in hearing more about the problems of training in these situations please refer to the following article.

These are extreme cases, but coaches tend to pick them to rationalize their training methods (e.g. Messi is not doing squats, why should my players?). They forget how much genetically gifted these guys are, and how technical they are. Sport is full of example of the elite players that did jack sh*t in terms of physical preparation and were still dominating due their great genetical traits and supreme technical and tactical skills (and especially in sports that are more technical and tactical dependent than physical – rugby vs. soccer). It is erroneous to base our training to the few extreme examples.

That’s why the guys stuck in the middle (and that’s like 80-90% cases) can drain the most potential (training transfer) from more general activities, in this case running-based conditioning.

Principle #6: Specific Chronic Load Syndrome

Specific chronic load syndrome is nothing else that saying differently that too much of a good thing is a bad thing. First time I’ve heard this concept formulated into ‘specific chronic load syndrome’ term was by Dan Pfaff

We can see this example popping out everywhere. In powerlifting, the debate variety vs. specificity gets another twist – by performing only (or having a great focus on) specific lifts (squat, bench, deadlift) ala Sheiko, one tend to ramp up the ‘groove’ or the skill part of those lifts, but also one tends to overload specific tissues that might needs some ‘rotation’, especially when done with high intensity, intensiveness and/or volume. This might results in chronic injury.

Going back to the running-based conditioning – if these are performed coaches tend to make them more sport-specific: a lot of start/stop and change of direction. Nothing wrong with this approach, but one needs to put things into context.

If the sport practices involve a lot of start/stop, change of direction done at high intensity, then putting more oil on the fire might end up with injury. I will get back to this idea in volume vs. intensity principle as well.

That’s why all general activities, involving running-based conditioning should supplement and complement sport practice.

For example, during the off-season when there is no or minimal sport practices, after one deals with injuries from the last season, it might not be very wise to base all of your conditioning to long slow running. Some more specific, higher intensive running with start/stop, change of direction might also be needed.

In pre-season where there is a lot of sport practices and small sided games, speed work and change of direction work, it might be wise to lower the number of running-based conditioning that involves a lot of start-stop and cutting action.

During the in-season, maybe all that is needed is high-intensity cross training on the bike or in the pool (non-impact). Yet, again this depends on the sport and athlete in question. Make sure to pay attention to acute relieving syndrome and work capacity as well.

All that is mentioned revolves around importance of context – thus there is no ideal solution without considering context.

Responses