High Frequency vs. Low Frequency: New Research Blasts Through the Age-Old Strength and Muscle Myth

If you’ve been a powerlifter or strength athlete for very long, chances are you’ve heard plenty locker room talk from both sides of the age-old programming argument: high frequency training vs. low frequency training.

Among all of the training variables you can adjust, it may be the most debated among strength coaches and athletes. But it makes sense—as high-level strength athletes we take pride and enjoyment in squeezing every last pound we can out of the bar.

On both ends of the spectrum are extremes, with Damnien Pezzuti and the Bulgarian squat everyday crowd pitted against fans of Eric Lilliebridge who claim lifting two or three times per week (and making sure you push yourself hard enough to puke while doing it) is the only way to true elite levels of strength and power.

Everybody seems to have an opinion. But when it comes to making the right choices for your training, how do you know which to pick? One study published just this year in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research may be the ultimate piece of evidence to finally put the dispute to rest.

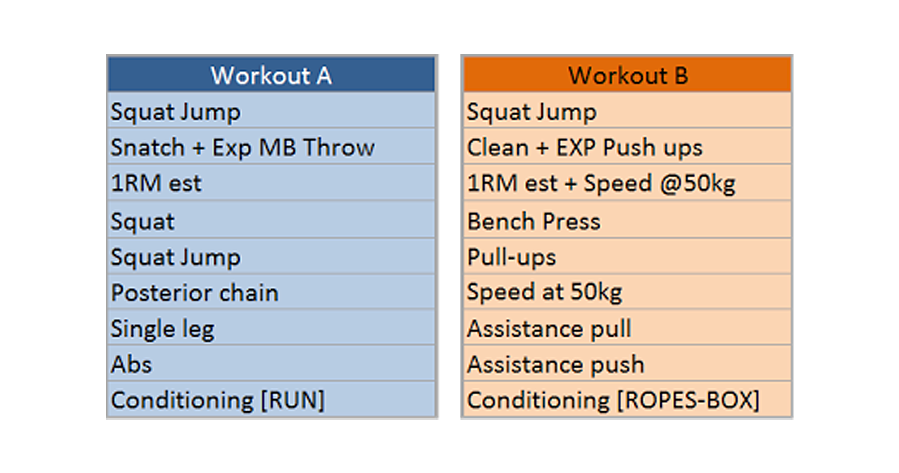

The study was simple. They took 28 resistance-trained males and put them into two groups at random:

- Low frequency group working out three times per week

- High frequency group working out six times per week

It is important to note that both groups worked out with the same level of volume and intensity. Following the end of the 6-week study, they measured a handful of metrics:

- Squat one-rep-max (1RM)

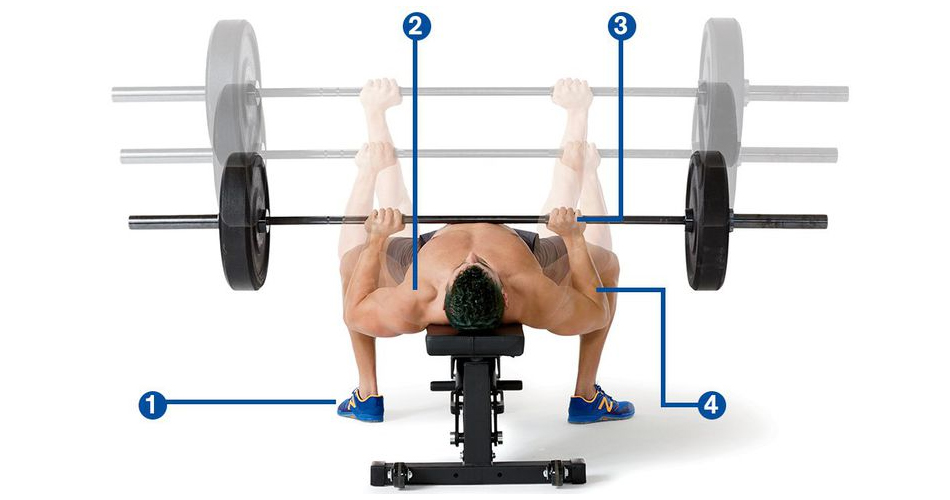

- Bench Press 1RM

- Deadlift 1RM

- Powerlifting total (squat, bench press, and deadlift combined)

- Wilk’s coefficient

- Fat-free mass changes

- Fat mass changes

In the end, surely they found that the high intensity group packed on more muscle?

Negative—both groups showed similar improvements in their maximal strength output and muscle mass. But the key really comes down to how much work was actually being done: their total volume (sets x repetitions x weight lifted).

Because both groups did the same amount of sets and repetitions there was no real difference in results. Interestingly, high frequency training in the upper body proved to be slightly more effective at improving strength in the bench press—suggesting that more, shorter bench press sessions per week at a higher intensity or load will lead to more gains than one or two workouts with lots of volume.

On the flip side, they also found that lower frequency training appeared to work better for lower body strength, suggesting fewer high-volume sessions are likely best.

Even more interesting, an additional study published in the same research journal found an intriguing connection between lower-body exercise volume and upper-body strength.

The researchers split up the 20 experienced strength athletes into two groups:

- High intensity only for both the lower and upper body

- High intensity for the upper body and high volume, low intensity for the lower body

At the end of the 6-week trial, they ran across something they didn’t expect. The researchers found that the group focused on hypertrophy for the lower body (high volume per session, low intensity) and strength for the upper body (high intensity, low volume per session) made significantly more results in their bench press 1RM (while strength changes in both groups for the squat were similar).

But how can you actually use this to improve your training or powerlifting programming?

If you are struggling with your bench press strength and feel that your squat and deadlift numbers are solid, there is a good chance that lowering intensity on squats to focus on more hypertrophy and mass will help better prepare you to hit a new bench press personal best at your next meet. And even if you are struggling with your lower-body lifts more, you should still be more conservative with heavy singles or doubles to focus on hypertrophy—at least according to the study.

But that doesn’t completely rule out high frequency training. While the research seems stacked against it, there are several pros to lifting more often and it is more than worth it depending on your goals or specific situation.

Benefits of High Frequency Training

If programmed intelligently, high frequency training can offer a few benefits that low frequency plans fail to deliver on. Olympic lifting and strength coach John Broz is well known for his thoughts on it.

“If your family was captured and you were told you needed to put 100 pounds onto your max squat within two months or your family would be executed, would you squat once per week? Something tells me that you’d start squatting every day. Other countries have this mindset. America does not.”

While his analogy may be bizarre, he does have a point—and has produced a handful of elite strength athletes to back up his claims.

- Larger improvements in neuromuscular coordination. A common topic of Greg Knuckles, the neurophysiological and neuromuscular coordination required for maximum strength output is often only gained through high intensity and high frequency—getting under a heavy bar as many times per week as possible.

- Better form from increased practice. If you’re going off of the common “10,000 hours to mastery” adage it makes a lot of sense why performing and practicing more often could prove to be beneficial.

- As a strength athlete specifically, higher frequency may allow for better specificity. As a powerlifter or elite athlete at any level, specificity is always a concern. While variation is good for building a general base of fitness and work capacity, it doesn’t translate to maximum strength: if you want to get really good at lifting heavy weights…you need to lift heavy weights. And the more you can practice at that highly-specific granular level, the better your results will be towards that goal.

High frequency training may also be more beneficial in smaller or less skilled lifters who don’t have the same recovery requirements as their stronger, more experienced counterparts. This is because while they can recover faster, they simply can’t do the same amount of damage—and thus need more training sessions per week to maximize their results.

With the positives, there are also negatives. If you are inexperienced or don’t know how to properly gauge your training fatigue, high frequency programs can lead to a higher rate of injuries. This is especially true for movements involving deep hip flexion such as the squats. In a longitudinal case report of a collegiate powerlifter with chronic groin pain, a major aspect of recovery involved backing off in the frequency department. As stress and bodily fatigue accumulate during the training cycle, it can be easy to overshoot or become too aggressive—which can be a one-way ticket to “snap city” and the physical therapy clinic.

Along with that, your form should already be rock solid before attempting to lift heavy more often or it could just lead to muscular imbalances or injury.

What about the perks of low frequency training?

Benefits of Low Frequency Training

While high frequency plans are the clear winner in specificity and neuromuscular adaptations, low frequency programs aren’t a complete lost cause. In some cases, the benefits may even become more desirable, but it will come down to each lifter’s individual situation.

- More consistent strength levels. If you are an in-season athlete or someone who wants to maintain a high level of strength at all times, the high fatigue of high-frequency training isn’t going to do you any favors in the consistency department. Some training days will feel great, and others will feel almost impossible to complete. For those who need consistency and results each time they step up to compete or play, lower frequency is probably better.

- Easier to peak and taper at a given time. When you can count on feeling rested at each training session, it becomes much easier to intelligently plan and progress into heavy lifts as the meet date draws closer and closer—you can rest confident that you will hit your next training prep milestone and not miss it due to abnormally-high fatigue or other variables more likely to affect you with a higher frequency approach.

While the chance of injury will also be lower, you are going to miss out on the positive neuromuscular benefits of lifting with high frequency.

Conclusion

Thanks to new research, we can finally put the frequency argument aside and spend our time more wisely where it matters—like in the gym getting better and crushing new strength records.

References:

- Michael H. Thomas and Steve P. Burns PhD (2016). Increasing Lean Mass and Strength: A Comparison of High Frequency Strength Training to Lower Frequency Strength Training

- Bartolomei, Sandro; Hoffman, Jay; Stout, Jeffrey; Merni, Franco (2018). Effect of Lower-Body Resistance Training on Upper-Body Strength Adaptation in Trained Men

- Physiqz.com – Powerlifting Programs and Routines

- Physiqz.com – Sports Hernia Injury: A Complete Full-Scale Review (Athletic Pubalgia)

- T-nation.com – Bret Contreras (2011). Max Out on Squats Every Day

- Colquhoun, Ryan, J; Gai, Christopher, M.; Aguilar, Danielle; Bove, Daniel; Dolan, Jeffrey; Vargas, Andres; Couvillion, Kaylee; Jenkins, Nathaniel, D.M.; Campbell, Bill, I; (2018)Training Volume, Not Frequency, Indicative of Maximal Strength Adaptations to Resistance Training

Responses