Special Considerations in Systemizing and Planning the Warm-Up

As a preface, if you haven’t already read the article that gave way to this follow-up article, I would encourage you to read Systemizing and Planning the Warm-Up first by clicking here.

Recap/Introduction

Of every component we are responsible for planning and implementing in sport preparation, the warm-up is the most consistent element across the annual cycle. Even in the densest or most critical competition phases, your team will begin the day by utilizing this transition period from everyday life into training, practice, or competition. Given the consistency of this portion of the program, your warm-ups should be more than a box-ticking, monotonous rush to make them sweaty and out of breath; it should be seen as a valuable developmental opportunity to build and maintain:

- Movement literacy/proficiency

- General work capacity

- Joint/tissue mobility

- Gymnastics/tumbling exposures

- Combat prep exposures

- Balance/proprioception

- Biomotor skill rehearsal/mechanical drilling

- Perception-action coupling

- Ultimately, specific preparation for the demands of the session ahead

However, as is life, there is nuance as to how this is implemented practically across the numerous contexts that practitioners reading this article will find themselves in. This brings us to the intent of this article in exploring those various settings and some of the considerations you might keep in mind as you plan warm-ups to fit your specific situation.

Sport-Specificity

It goes without saying that specific sporting demands vary widely across the approximately 200 sports with recognized federations in the world. Australian Football is played on a oval-shaped pitch that can be 185m long and 155m and features high speed running and CODs, long accelerations, decelerations, collisions, and even kicking over 4 quarters of 20 minutes each. Singles tennis, on the other hand, is played on a rectangular court that is 12m long and 8m wide and features frequent swinging of a racket, short accelerations, decelerations, CODs, and zero direct contact with the opponent over durations of 4 or more hours.

It should also go without saying that the warm-ups designed for each of these sports should account for some of the specific features of these sports. Consider how the size of the competition area, sport rules, techniques, and tactics afford particular movement demands, whether athletes will directly engage with opposition, or more specific movement demands that incorporate implements or athlete appendages.

For example, a sport like tennis probably doesn’t need to incorporate any sort of max velocity/upright running drilling within warm-ups, or any sort of combat/collision prep, because these are demands that will never occur within the sport. Conversely, the inclusion of an implement like a tennis racket should warrant some dedicated time in your warm-up to prep athletes for swinging a racket.

Position/Event-Specificity

In a similar vein as the above, consideration should be given for athletes who have vastly different demands due to their positional demands within a sport. In American Football, I think there are 4 functional groups worth differing warm-ups, particularly as it pertains to warming up to do the sport itself:

- Linemen operate in a very small space of the field while attempting to push and redirect other linemen, creating contact demands on every play.

- Skill players are accelerating, decelerating, jumping and changing direction at varying distances and velocities, with limited contact demands, some of which can occur at very high velocities.

- Quarterbacks can have varying locomotive demands dependent on the style of offense they are in, but will inevitably have some element of accelerating, decelerating, and changing direction, while also taking on some contacts/collisions, and needing to throw a ball at varying distances and velocities.

- Kickers/punters will perform a high intensity kicking action infrequently over the course of 3-4 hours.

Suffice it to say that beyond an early stage generalized warm-up that can be applied to all, these positional groups may warrant more specific late stage warm-up phases prior to transitioning to the sport session itself that are reverent of these varying positional demands.

Competition

When it comes to the most important, intense, specific, and complex stressor your athletes will experience, it is essential to counterbalance those superlatives with two time-tested principles:

- KISS (Keep It Simple Silly) – Competition is not the time to show off the depths of your exercise selection and progression toolbox; it is a time for a consistent, remedial routine that the athletes can execute without much thought. This means deploying the simplest regressions of the movements and mobilizations that you believe help transition the athletes into the rest of the precompetition warm-up and the competition itself, as well as fill in the gaps of what the rest of the precompetition warm-up may not give the athletes that they will need during competition. For example, if the main feature of a precompetition warm-up for soccer is small-sided games, it may be prudent to allocate more time to building up to some high-speed running, and only a little bit of time to COD exposures since they will get plenty of CODs from the small-sided games, and in a more applied context at that. Make sure you have taken the athletes through your competition warm-up a few times prior to the first competition so they are familiar with it.

- Less is more – This one is pretty straightforward- use less distance, duration, and reps in your prescriptions than you would in a training session warm-up. Keep your overall warm-up length as short as it can be without cutting corners. Competition is a big cost; save more in the bank accordingly.

Youth

While not the focal point of the book, I found The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt to do a fantastic job of summarizing how and why the art of play is being lost in modern younger generations. We didn’t realize it and we didn’t need to, but when we played tag as kids, we were learning how to accelerate, decelerate, and change direction as we perceive other kids doing the same to evade being tagged or attempt to tag us. Culturally, we were learning how to make plans with others to be social, set and play within the rules of the game, and navigate conflict if someone pushed somebody else too hard. We didn’t think about any of this; we just did and benefited from it developmentally, knew we were ultimately having fun, and look back fondly on these simpler times in childhood.

This should broadly inform how those working with youth athletes should look to coach them- by making it fun and gamified. Part of the responsibility incumbent to youth coaches is to create positive, formative associations with physical activity/sport for kids that last them a lifetime, so they can be healthier and more productive members of society later in life. In working with younger athletes, the goal should be to expose them to as many fundamental movement patterns and tasks, without them perceiving it as just tiresome physical activity.

By having to crawl under low track hurdles, jump onto a box, or hop in and out of a hopscotch ladder on one leg as part of a “warm-up obstacle course”, athletes are getting exposure to bear crawling, jumping, and pogo hopping in a fun way where they don’t realize they are warming up. There will be a time and a place in their athletic lives where more structure is needed during a warm-up, but with young athletes who are cultivating an enjoyment of being physically active, the more regimented approach can wait.

Jeremy Frisch is an outstanding coach in the space of youth athletes- you can follow him on instagram @jeremy_frisch17 and see the numerous ways he exposes youth athletes to gamified physical development, as demonstrated in the video below:

Conclusion

The best warm-up your athletes can do is the warm-up that aligns with:

- What type of session they are preparing to do

- The demands of the sport and their position

- Where they are at in their long term development

- What you’re comfortable with coaching

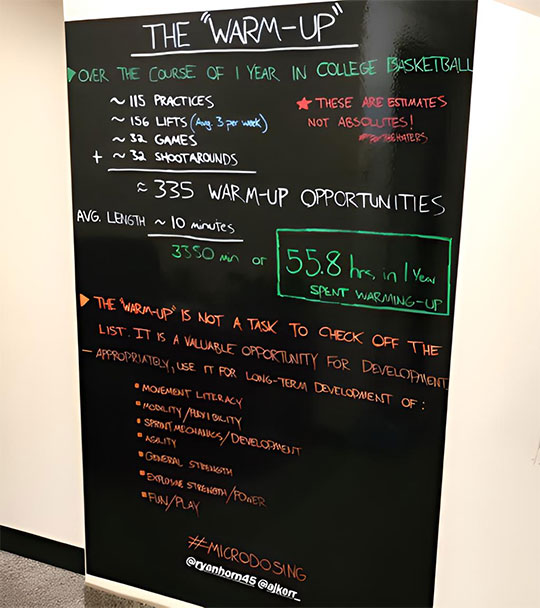

By combining these considerations with the principles and framework of the first article, a segment of the physical preparation program that is often a monotonous afterthought becomes a powerful developmental opportunity. As a reminder, the below image from Ryan Horn shows how warm-ups represent 56 hours over the course of a year in college basketball- don’t let over 2 full days of time with your athletes go to waste.

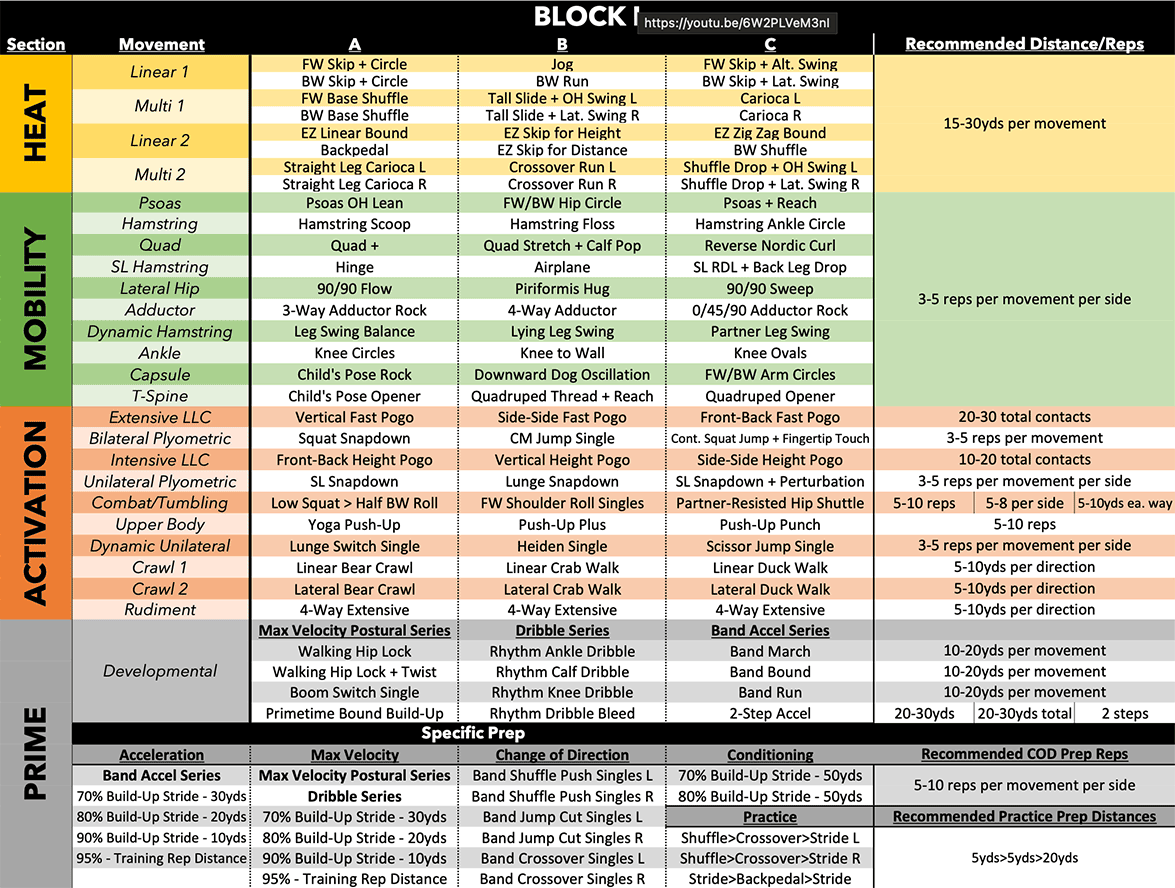

The 4-Block Warm-Up Template is now available in our online shop.

The 4-Block Warm-Up Template is a structured system for planning and progressing warm-ups across the year.

What’s included:

- 3 complete warm-up block progressions

- 4 progression levels for every key movement

- Video demonstrations for all included movements

- Rep and distance implementation guidelines

- Flexible structure adaptable to your sport and season

Responses