The Integrative Approach to Strength and Conditioning

“It depends” is one of the most factual answers to any philosophical question to inform practice…

On reading both early and contemporary research, books and case observations, as well as when attending conference presentations, lectures and consultancies, one is amazed by the diversity of models, theories, philosophies, rationales and approaches to address similar problems. Such a diversity of representations and explanations across domains is known as the ‘fact’ of pluralism (Mitchell., 2002). The athletic performance area is particularly good evidence of such multiplicity of representations, methodologies and rationalizations, which all branch from interpretations of a science that aims and fails to explain a complex world with simple world models (Jovanovic, 2020). One second explanation for this diversity is that pluralism reflects immaturity of the science (Kuhn, 1962). Have you heard a really experienced practitioner say, “the more I learn, the more questions I have”? I think we all have…

Pluralism reflects complexity, and the ‘fact’ that pluralism is evidenced largely across all disciplines, suggests that the deeper we dig into a subject matter, the greater complexity we will find. This is why the ‘optimal’ training program does not exist. The best investment when seeking to understand, select and apply from a multitude of competing and compatible models of ‘knowledge’ (I like the term ‘philosophical thinking’ better than ‘knowledge’) is to adopt an integrative approach; i.e. one that analyzes theoretical paradigms, and purposely draws a combination together (Prochaska & Norcross, 2018). This especially applies to the strength and conditioning coach from matters as small as exercise selection to matters as large as advanced periodization, multidisciplinary decision-making and leadership approaches. For a more in-depth exploration of the integrative pluralism paradigm the reader is directed to: Mitchell, 2002, 2003; Jha, 1995; Wimsatt, 1987; Hawkins et al., 20101.

In this highly philosophical article, I don’t want to tell anyone what to do or how to do things (I am far too inexperienced to do that). Instead, I will aim to promote the rationale that the pluralism in the strength and conditioning practice, should coexist with an integrative approach from coaches. From looking at historical accounts, we can appreciate that our understanding of complex biological phenomena is far from complete, to an extent that uncertainty can be inevitable (Kitcher et al., 1990); let alone our development of practical coaching models… As such, an integrative approach may safeguard sustainability for coaches and possibly move us a tiny bit closer to (non-reachable) ‘optimality’.

One of the biggest problems in practice, regardless of domain, is the false idea of establishing causality. Let me quote philosopher William Wimsatt:

“Any model implicitly or explicitly makes simplifications, ignores variables, and simplifies or ignores interactions among the variables in the models and among possibly relevant variables not included in the model”.

Inherently, regardless of the targeted physical adaptation, all training interventions and performance strategies or practices have underlying assumptions about biological homeostasis. Let me explain better, to unequivocally understand how a particular biological system will behave in accordance to a specific training intervention, all other divisions of homeostasis are assumed to be held constant (see Catwright, 2000). However, we know that training is an interruption to (physiologically speaking) normal state, this to say that intervening in one area (i.e. introducing bias) may well introduce variance (thus unpredictability) in another area (Jovanovic, 2020). Whether that is at architectural, psychological, genetic or metabolic levels is a whole other question, but the confusion lies and conflict occurs when we try to explain real-world responses with ideal-world models. We don’t need to go as far as the popular hamstring injury research in running-based sports. How many studies have shown eccentric hamstring strength and fascicle length to be predictors of reduced risk of hamstring injury, in static-world models? Shit tons (Stanton et al., 1989; Croissier et al., 2008; Askling et al., 2003; Timmins et al., 2016; Seymore et al., 2017; Lovell et al., 2018; …2). But why is hamstring injury incidence still so high? Some say increasing intensity of games, inadequate load monitoring, lack of compliance (see Bahr et al. [2015] for very neat observations), asymmetrical strength… the list goes on… I say a lack of consideration of confounding variables, jumping to noise, an inappropriate balance between bias and variance (i.e. ‘putting all eggs in one basket’), bad luck and the above objective measures may fit in the mix. In the words of philosopher Sandra Mitchell (whom I have quoted numerous times already and will continue to do so):

“Reductionism is compelling, yet reductionism doesn’t capture the realities of scientific enquiry”.

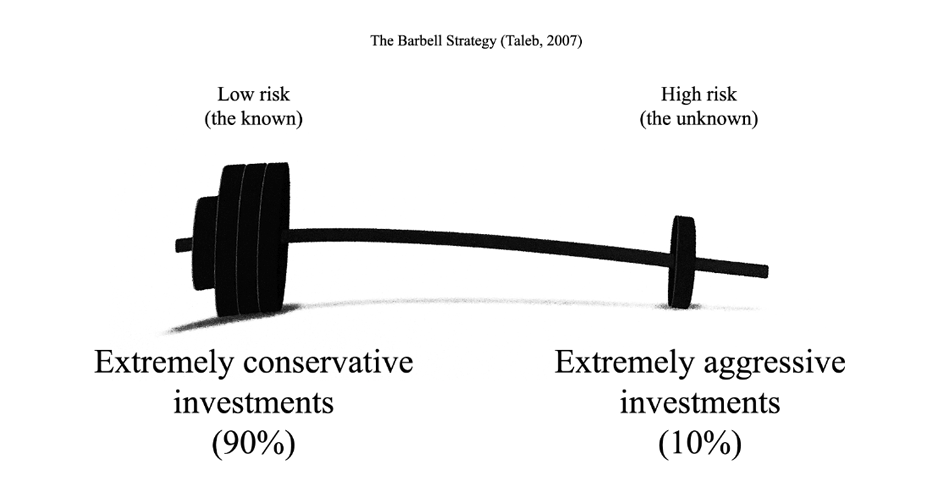

Of the alternatives to reductionism in philosophical or scientific enquiry and complex real-world practice, the most robust and realistic to the limits of human understanding are integration and integrative pluralism. An integrative approach we know may be defined as an intentional and scientifically-derived combination of theoretical paradigms (Prochaska & Norcross, 2018), and to follow, I would like to focus on how this philosophical approach may inform the strength and conditioning coach’s strategies for sustainability (of self and of athletes). Now, an integrative approach protects from unpredictability in the same way that betting $100 (each) on 10 random horses in the horse races reduces your losing potential compared to betting $1,000 on one random horse. Yes, this level of unpredictability may be greater in competitive sport. Of concern in the sports science and strength and conditioning field is how undervalued the ecological validity of findings is. I recently finished doing my literature review for master’s research project (which involves a nutrition investigation) and it is remarkable how little ecologically valid findings I found. How is it possible that researchers are still able to title papers “X (did or did not) have an ergogenic effect on Y sport”, and employ laboratory-based testing? I don’t care how your recreational sport participants did in a cycle-ergometer test! It’s like teaching a man to fish in a fish tank full of fish and sending him off to the open sea with a fishing rod. Anyways, enough of the rant but this process showed me early-on the importance of ecological validity in study design and although it may mean less control (tell me one sport that provides a controlled environment… I’ll wait…), ecological observations can provide truer theory of practice.

Let’s consider periodization ideologies for a second. I know that Mladen has nailed this topic in multiple occasions in the past, however, it presents an appropriate example defending the strategic rationale behind integralism. In ‘Transfer of training in sports’ Dr. Bondarchuk and Dr. Yessis profoundly outline, amongst many other concepts, the ‘Block’ method of periodizing training cycles. The rationale behind such planning is that in athletics it is necessary to first develop the physical capabilities and only after this, perfect technical mastery. Thus, the block method of constructing training cycles proposes preparatory periods in separate blocks of physical and technical preparation. In terms of biological adaptation, it makes total sense. Those in agreement with this concept do not believe that simultaneously introducing means of technical preparation into the training process with ‘general’ physical training would yield beneficial responses (Bondarchuk & Yessis, 2007). Now, we can talk for ages about the pros and cons of different periodization ideologies, but the point is that these are ideal-world models that assume predictability of the environment, and as such are able to bias particular areas (e.g. hypertrophy, strength, power cycles). This may work better with specialist-athletes that have rigid competition calendars, peaking dates and operate in a more ‘controlled’ or ‘predictable’ environment. However, extracting such models to any other competitive sport is a reductionist and high-risk approach (i.e. like going all in with nothing to scare the opponent in the Black Jack); especially in modern day where athletes experience so many other societal loads3. What happens when your players are inevitably getting bigger and slower from hypertrophy cycle and they get called for an international competition and do a hamstring? I will give you another example. Recently, the ‘alactic-aerobic’ or ‘High-Low CNS’ approach to conditioning has become increasingly popular amongst strength and conditioning coaches. The rationale being that alactic drills provide an opportunity to do high-quality work, aerobic drills provide an opportunity to recover or regenerate and train oxidative capacity and medium intensity (lactic) drills just accumulate unnecessary fatigue (i.e. high waste product, not hard enough to adapt, not easy enough to recover with) (Francis, 2008). Again, from a rationalist perspective, this makes total sense, and for training speed in sprinters it is probably the optimal choice. However, this is an ideal-world model, so an integrative pluralist cannot marry to it. What about the worst-case scenario where the conditions are oxygen deficient and one cannot recover easily from repeated alactic efforts? This is a particularly important consideration for intermittent sport athletes (e.g. soccer, basketball, hockey, rugby league) where a substantial proportion of the work is done in that ‘lactic’ zone (Gabbett, 2012; Narazaki et al., 2009; Stojanovic et al., 2017; Bloomfield et al., 2007). And this is the reason why, as an integrative pluralist, I identify with the Agile Periodization approach, whereby a balance between bias and variance is adopted to minimize risk / cost from unpredictable or unprecedented occurrences (Jovanovic 2018, 2020).

The same principle holds true when trying to inform programs from a fatigue management perspective. The reductionist or sophist perspective (i.e. one that is concerned with the shortest path to success in practical matters and emphasizes immediate needs of the individual, e.g. set guidelines and reductionist answers) adapts immediately to the athlete with sole consideration for objectivity and rationality. In the strength and conditioning area, this is the coach that immediately re-scripts the session from a wellness, soreness, CMJ, RPE, HRV, brain activity, etc. reading. On the opposite, an irrational coach will omit or disregard all available information and ‘push for adaptation’ (i.e. take a forceful ego-orientated approach). The integrative or Socratic perspectives involve developing a broader foundation of knowledge and insight in navigating practical problems. A coach working from a Socratic approach might aim to take a more ‘wide breadth’ approach which considers characteristics relevant to the athlete on a micro-basis. For example, a consideration of both short (acute) and long-term (chronic) patterns or changes, logistical issues, naturalistic observations, similar past experiences, intuition, etc. This practitioner chooses also sustainability over optimality, but searches a fine-tuned balance between interpreting the data and interpreting the human in front of him. Although two different concepts, a mix of sophist and Socratic approaches can be effectively used and probably should be used by practitioners (Poczwardowski et al., 2004); different times call for different measures. The fine-tuned balance of approaches may stop a coach from jumping to ‘noise’ without pushing too far. For a more in-depth exploration of pertinent examples please refer to the further readings provided. Especially, I would like to recommend three key readings for you, the reader, to enjoy. 1) ‘Why Bayesian Rationality Is Empty, Perfect Rationality Doesn’t Exist, Ecological Rationality Is Too Simple, and Critical Rationality Does the Job’ by Max Albert. 2) ‘Biological complexity and Integrative Pluralism’ by Sandra Mitchell. 3) ‘How to be Rational about Rationality’ by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

To conclude… (finally!)

There are, in my opinion, very few “heuristics” (to use Complementary Training vocabulary), when it comes to approaches to coaching, but let’s be real… an integrative approach is most robust and sustainable. I will give you one last example of where the integrative approach (i.e. and balance between bias and variance) applies. At times it may not be too costly to take an authoritarian-type leadership approach when dealing with the athletes. In fact, some circumstances may call for it; but, extend that for a long-period of time and unless you are married to the club CEO you’ll be out of there soon. At times, a more inter-personal or acceptance focused leadership approach may allow to build comradery, to uplift the training environment or to build rapport with the athletes; but, let loose for too long and you’ll be losing authority in your role, losing games or dealing with injuries left, right and center.

Two of my favorite quotes related to this thought process are:

I hope you enjoyed the article and maybe it stimulated some new thinking. My key messages would be:

- The unpredictability of an environment calls for an integrative pluralist orientation. With this said, the greater the frequency, depth and quality of review and retrospective of the training program and process, (in theory) the closer one will get to bulls-eye.

- Seek for a balance between bias and variance.

- Value ecological validity – findings from data collected in unstable environments (real-world) are more likely to sustain in practice (real-world). Don’t be compelled by reductionism!

Footnotes

- 1 Integrative approach to understand complex systems in genomics paper

- 2 These papers are not in the reference list, as they are not in the scope of this article (just examples)

- 3 How much time do your athletes spend in front of a screen?

References

- Bahr, R., Thorborg, K., & Ekstrand, J. (2015). Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams: the Nordic Hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med, 49(22), 1466-1471.

- Bloomfield, J., Polman, R., & O’Donoghue, P. (2007). Physical demands of different positions in FA Premier League soccer.Journal of sports science & medicine, 6(1), 63.

- Bondarchuk, A. (2007). Transfer of Training in Sports (M. Yessis, превео). Michigan: Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge University Press.

- Francis, C. (2008).The Structure of Training for Speed (Key Concepts 2008 Edition)(p. 18).

- Gabbett, T. J. (2012). Activity cycles of national rugby league and national youth competition matches.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research,26 (6), 1517-1523.

- Hawkins, R. D., Hon, G. C., & Ren, B. (2010). Next-generation genomics: an integrative approach. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11(7), 476-486.

- Jha, S. R. (1995). Michael Polanyi’s integrative philosophy (Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education).

- Jovanović, M. (2018). HIIT Manual: High Intensity Interval Training and Agile Periodization. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Jovanović, M. (2020). Strength Training Manual: The Agile Periodization Approach. Volume One and Two.

- Kitcher, P. (1990). The division of cognitive labor. The journal of philosophy, 87(1), 5-22.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientifi revolutions. The Un. of Chicago Press, 2, 90.

- Mitchell, S. D. (2002). Integrative pluralism. Biology and Philosophy, 17(1), 55-70.

- Mitchell, S. D. (2002). Integrative pluralism. Biology and Philosophy, 17(1), 55-70.

- Mitchell, S. D. (2003). Biological complexity and integrative pluralism. Cambridge University Press.

- Narazaki, K., Berg, K., Stergiou, N., & Chen, B. (2009). Physiological demands of competitive basketball.Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports,19(3), 425-432.

- Poczwardowski, A., Sherman, C. P., & Ravizza, K. (2004). Professional philosophy in the sport psychology service delivery: Building on theory and practice. The Sport Psychologist, 18(4), 445-463.

- Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2018). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Wimsatt, W. C. (1987). False models as means to truer theories. Neutral models in biology, 23-55.

Responses