Interview With Rob Gathercole on Alternative CMJ Analysis and NMF

I read two great papers on using alternative metrics when analyzing countermovement jump (CMJ) with the goal of evaluating both acute (neuromuscular fatigue, or NMF) and chronic training effects written by Rob Gathercole et al.

I was amazed by how much new food for thought have been inside and how great was the novel combination of inferential statistics using effect sizes and confidence intervals and typical variation in the metrics, without a single mention of p-value. Hence I had to interview Rob on how did he managed to do that.

Mladen: Thanks for your time to take this interview with Complementary training Rob. Before I start picking your brain, can you tell something about yourself for the readers?

Rob: Thanks very much for the opportunity Mladen! I’m originally from the UK, but have been living on the West Coast of Canada for the past six years. I have a Masters in Sport Nutrition, and recently completed my PhD, focusing on countermovement jump (CMJ) testing for neuromuscular fatigue (NM) monitoring. During my PhD studies I feel hugely fortunate to have been supervised by fantastic applied practitioners, Ben Sporer, Trent Stellingwerff, and the late Gord Sleivert. Alongside my studies I have split my time between roles in sport technology and elite sport with the Sport Innovation Centre and Canadian Sport Institute Pacific, respectively. My present position is within the Whitespace™ department at lululemon athletica, where I’m currently enjoying the hustle and bustle of applied research, product development, and industry!

Mladen: You recently published couple of great papers [LINK, LINK, LINK] on vertical jump [CMJ] assessment to quantify both acute (neuromuscular fatigue; NMF) and chronic effects of training. Can you take the findings of those two papers and comment on the usual strategy of S&C coaches and sport scientist to use vertical jump HEIGHT as one of the typical variables of CMJ to evaluate acute NMF and chronic effects of training?

Rob: Jump height is really simple to measure and discuss. It also appears to make intuitive sense that any deficit in NM function contributing to the jumping movement would be evident as decreased jump height. However, changes in jump height are not consistently observed in response to fatiguing exercise or chronic training. As such, rather than reducing CMJ analyses to an assessment of jump outcome (i.e. height) or single-points within the jump (e.g. peak power/force, minimum velocity), we began to explore the CMJ as a whole movement.

In the first investigation we explored how CMJ performance in sub-elite athletes was influenced by a fatiguing protocol. We found that most aspects of CMJ performance were diminished immediately post-exercise, lending support to the use of jump height. However, by 72-hour post, while jump height and most single-point CMJ variables had recovered, alterations in jump strategy (i.e. increased jump duration, and decreased eccentric utilization) persisted. Therefore it appeared that (1) alterations in jump strategy may require longer recovery time, and (2), that the more common approach to CMJ analysis may inadequately describe NM fatigue status if jump height can be recovered but the movement involved remains sub-optimal.

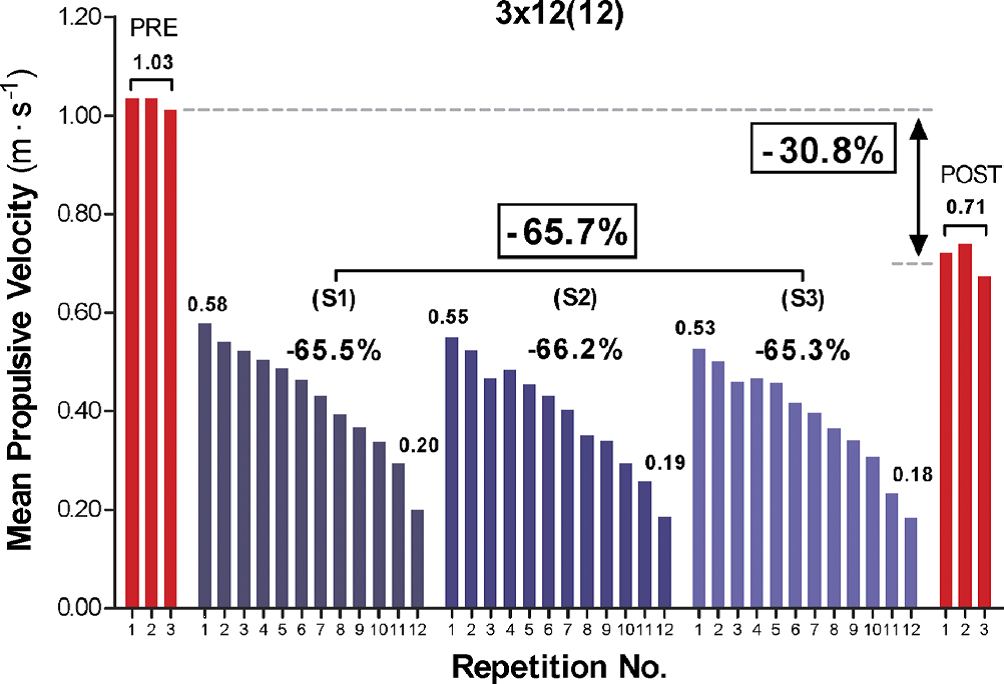

Utilizing the same approach, we then explored acute fatigue and chronic training-induced responses in elite athletes. In the acute fatigue condition we observed something really cool. After having these athletes perform a fatiguing workout, they were still capable of producing the same jump height and peak power (which increased!). However, how they did the CMJ was altered, taking a fraction of a second longer to perform it, with a reduced eccentric component. In contrast, the chronic training appeared to markedly improve jump strategy (i.e. decrease jump duration & increase eccentric utilization) whereas peak power and jump height were again largely unchanged.

Together, these investigations suggest that rather than focusing on jump height (or related variables), practitioners would seem better served by additionally assessing how the CMJ performed. This appears applicable regardless of whether fatigue or training-induced adaptive responses are being assessed, increasing the capacity to detect such changes. Furthermore, these results also indicate that elite athletes may be able to retain the capacity to achieve maximal CMJ performance despite fatigue, by adjusting how they perform the movement.

Mladen: I really like how you emphasized the importance of “looking under the hood” to get a glimpse on how certain outcomes are reached, rather than relying solely on outcome measures (like CMJ height). But to look under the hood one needs specialized equipment (e.g. force plate and LPT) and not everyone can afford it. Luckily more and more gadgets (like bar accelerometers) make this cheaper. What are your thoughts on their potential use and their error of measurement? Can these be used to complement simple vertical jump height and get some glimpse into mechanics/process behind the jump? Also, what are you cheap and useful recommendations one can use?

Rob: Correct, the use of the specific methodologies we used is likely restricted to those with similar equipment. However, as you’ve highlighted, the key is in assessing how the jump was performed not just what was produced, and I think this is entirely possible with other equipment. For example, many of these more inexpensive measurement systems can provide measures of strategy-based variables (e.g. force at zero velocity, duration-, rate-based), while they also allow the extraction of raw data so that the jump movement as a whole can be explored. Therefore practitioners can adopt this approach without the need for the same equipment.

Nevertheless, a difficulty with strategy-focused analysis is that how the movement is performed does tend to be less consistent than other CMJ measures. This means it is essential that the equipment and variables describing CMJ strategy are accurate and precise.

Similarly, the number of steps required for calculation of a variable may increase associated error and noise, and so always try to use the most direct measurement wherever possible. For example, jump height calculated using flight time might exhibit greater capacity for neuromuscular fatigue detection than when it is derived through the impulse-momentum equation (unpublished observations; Cormack et al. 2008). Although both variables reflect the height attained in the jump, they differ in the number of steps required in their calculation, with flight time being more direct.

To summarize, as long as the measurement system provides sufficient sensitivity and reliability then I think this approach can be incorporated into most monitoring protocols and with most equipment.

Mladen: You have used some very simple and intuitive graphs to visualize both SWC, typical variability (inter-day CV) and confidence intervals. I am hoping more applied researchers are starting to acquire such practices. We all know Martin Buchheit have struggled with editors when trying to push this new way of magnitude-based inferences. How did you manage to get published without a single p-value?

Rob: There have been some outright rejections of the methods and so some persistence is required! On the other hand, acceptance does appear to be increasing as I’ve also had reviewers complement the approach. It seems that people are recognizing the difficulty with traditional statistical approaches in inferring changes in the training environment when subject numbers are generally too small and where there are many confounding variables. Therefore, I’d definitely encourage people not to be put off using these methods, just be wary of the journal approached (i.e. the more applied journals appear more open), be ready to argue your case and be prepared for rejection.

Mladen: To finish up, can you give us some recommendations regarding the most practically do-able and useful (reliable) CMJ assessment protocol? How often, when, with or without feedback and what type of feedback (height/power, etc.), how many jumps, sets, rests and how to analyze those scores (max, average, etc.) when it comes to evaluating both acute (NMF) and chronic effects of training?

Rob: Here are some of the methods we’ve used:

1) Encourage athletes to perform the jump ‘as they normally would’. We used these instructions to avoid putting any limits (e.g. pre-defined countermovement depths) on how the jump was performed so that we could better explore changes in adopted jump strategy.

2) Rather than having each athlete perform multiple trials consecutively, instead cycle through groups (i.e. 5-10) so that athletes can be recovering while others are being tested. Can get through big groups much faster this way!

3) We always used multiple trials from the same athletes. I’d recommend at least 3 CMJ trials per athlete (in addition to warm-up trials for re-familiarization with their ‘normal’ jump technique), with the two ‘most similar’ trials (rather than ‘best’) used in further analysis. We used this approach to decrease the influence and likelihood of skewed data resulting from a particularly anomalous trial (i.e. these tests take ~1sec to perform and so slight alterations in technique can have quite dramatic effects on measures of jump strategy!). As we wanted to consider the entire jump movement, we identified the ‘most similar’ trials using EccConMP (the mean power over both eccentric and concentric phases divided by the total jump duration) as we found this best able to describe the overall CMJ performance.

4) Avoid using the same thresholds for detecting meaningful changes with all athletes. Athletes differ in their consistency and so what may be unimportant in one athlete may be huge to another. Therefore individualize thresholds whenever possible (e.g. effect sizes based on the typical variation within an individual as opposed to the typical variation between individuals). This is particularly important when assessing jump strategy as different individuals can use markedly different strategies whereas repeated jumps by the same individual differ to a far lesser extent.

5) Regarding the best variables to monitor, we suspect that NM responses differ in different circumstances depending on numerous factors (e.g. intensity/duration/type of activity performed, training status/history, genetics, age) and so it’s likely impossible to recommend specific variables for each and every situation. Practitioners should therefore identify which variables are subject to change in their particular athletes.

6) Saying that, a few strategy-focused variables appear more repeatable and sensitive than others. For example, force at zero velocity (for eccentric function) appears to offer fairly good repeatability and appears useful for inferring changes in strategy during the eccentric phase. Likewise, duration variables (e.g. eccentric/total duration) are repeatable and appear sensitive to acute fatigue and chronic training. However, it is important to note that duration variables may be unchanged but strategy may still be affected. For example, in a paper currently under review, we’ve observed that the accumulation of NM fatigue can result in peak force occurring at different stages of the jump (i.e. at concentric phase onset vs. just prior to jump take off), whereas jump duration was unchanged.

Mladen: Thank you very much for great insights Rob. Wish you all the best and a lot of published papers

Rob: Thanks very much Mladen, it’s been an absolute pleasure!

References

- Cormack, S. J., Newton, R. U., & McGuigan, M. R. (2008). Neuromuscular and endocrine responses of elite players to an Australian rules football match. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 3(3), 359-374.

Responses