The Science of Gaelic Football

Gaelic football is one of the most played sports in Ireland & is organized & governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association and holds amateur status. The sport is far from the amateur in nature, with players training up to 5x per week, following a demanding training schedule.

Introduction

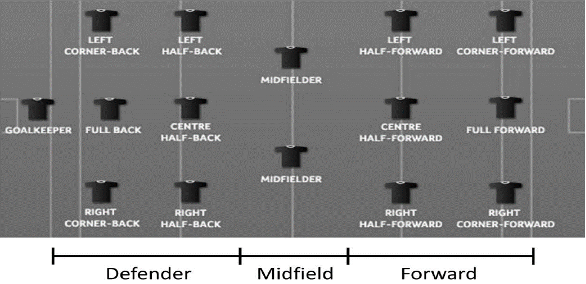

Gaelic football is one of the most played team sports in Ireland and is organized and governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) (Brown and Waller, 2014; Cullen et al., 2013). Unlike other team sports, Gaelic football holds amateur status, whereby players play for the love of the game and may only receive expenses for playing at the elite level (Mangan et al., 2018; Roe and Malone, 2016). Although amateur by name, the sport of Gaelic football is far from amateur in nature with elite players training up to five times per week, following a highly structured and demanding training schedule consisting of both on-field and off-field sessions (Beasley, 2015; Mullane, Turner and Bishop, 2018). Gaelic football is played at both an elite and sub-elite level. At the sub-elite level, players play for their local club teams whereas, at the elite level of Gaelic football involves a pool of the best players in each county who play at intercounty level (Malone et al., 2016b). The National Football League (NFL) and the All-Ireland Football Championship (AIFC) represent the two major elite intercounty competitions (Mangan and Collins, 2016). Gaelic football is played on a field that can be up to 40% larger than a soccer pitch, with a length of 130-145 metres (m) and width of 80-90m (Brown and Waller, 2014). At the sub-elite level matches consist of two periods of 30 minutes, while at elite level the halves are 35 minutes long, half time is 15 minutes (Brown and Waller, 2014; Roe et al., 2018a). On the field, two teams of 15 players compete with each team consisting of a goalkeeper, 3 full backs, 3 half backs, 2 midfielders, 3 half forwards and 3 full forwards (Figure 1) (Cullen et al., 2017).

Figure 1: Categorisation of playing positions adapted from (Cullen et al., 2017).

The objective of Gaelic football is to outscore your opponent and scores are kept in two forms: points and goals. A goal, which is worth three points, can be scored by kicking or punching the ball into the net, while a point is scored when the ball is punched or kicked over the crossbar (Orejan, 2006). The skills performed in Gaelic football include: a high catch, accurate kicking for long distances, hand passing, tackling and the solo running (Reilly and Collins, 2008). The intercounty Gaelic football season can be split into four phases: pre-season (December – January), in-season 1 (January – March), mid-season (March – May), in season 2 (May – August). The in-season period from May to august is the most crucial part of the season for intercounty teams as the AIFC takes place during this period (Roe et al., 2018b).

Physically, Gaelic football is one of the most demanding team sports due to the multiple physical contacts using very little protective gear, exposing the players to a high risk of injury (Reilly and Keane, 2002; Wilson et al., 2007). The multi-directional nature of the sport, Gaelic football requires players to undertake a number of unpredictable high intensity efforts separated by periods of lower intensity pace (Cullen et al., 2013; Malone, Solan and Collins, 2017; Collins, Solan and Doran, 2013). For an individual footballer, the time spent in possession and game-based activity challenging for possession is approximately 2.2-2.7% of playing time (Hulton, Ford and Reilly, 2008; McGahan et al., 2018). Research has observed that elite Gaelic footballers typically cover between 8160 – 9222m of which ~13 – 19% is covered at speeds > 17km/h, which is classified as high speed running (McGahan et al., 2018; Collins, Solan and Doran, 2013; Malone et al., 2016b; Malone et al., 2017a). This results in approximately ~15 high speed metres per minute (McGahan et al., 2018). Due to this complex and unpredictability of the sport, players must possess multiple physical characteristics such as aerobic and anaerobic capabilities, strength, power and speed which can aid successful performance (Reilly and Keane, 2002), which will be discussed throughout.

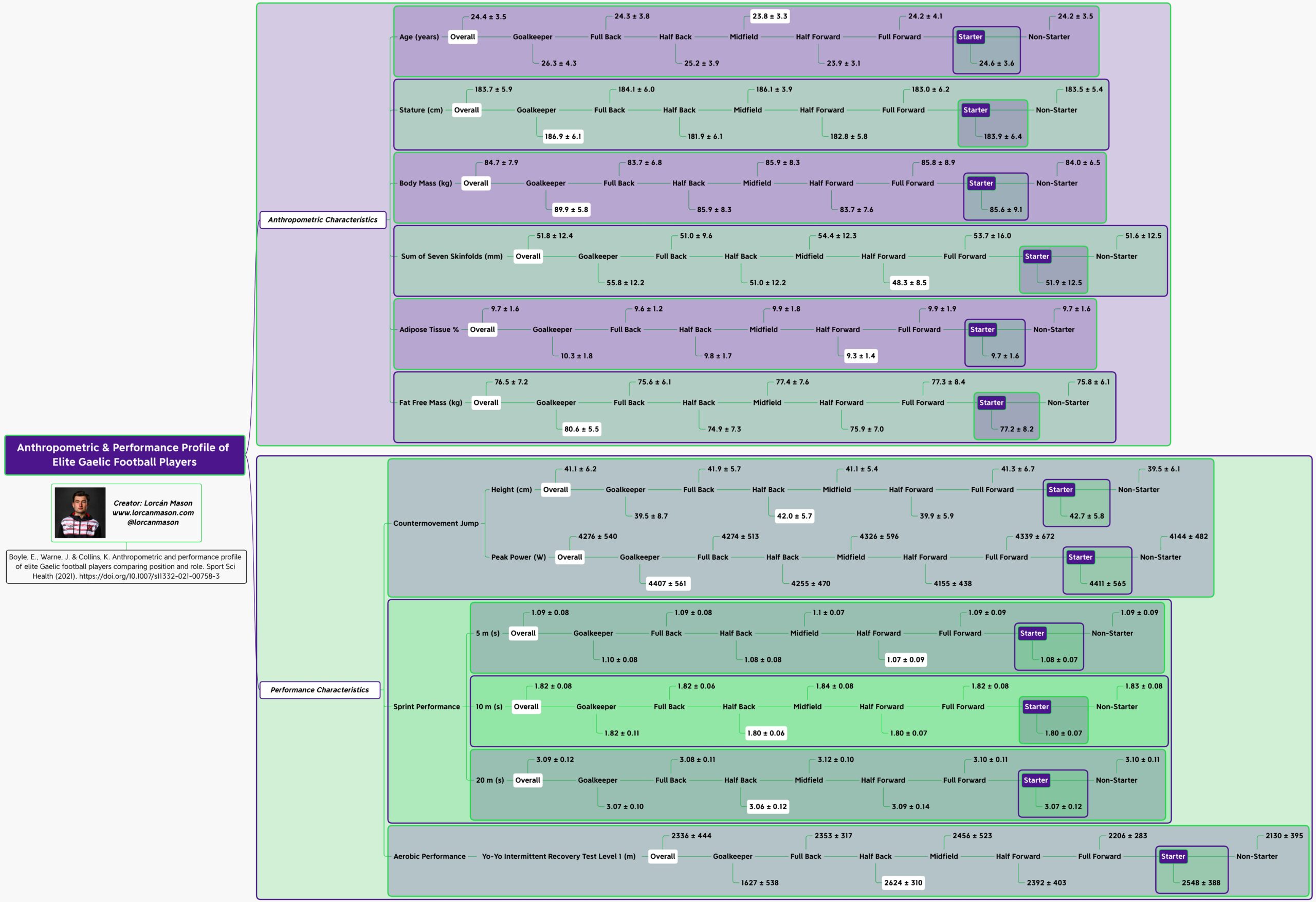

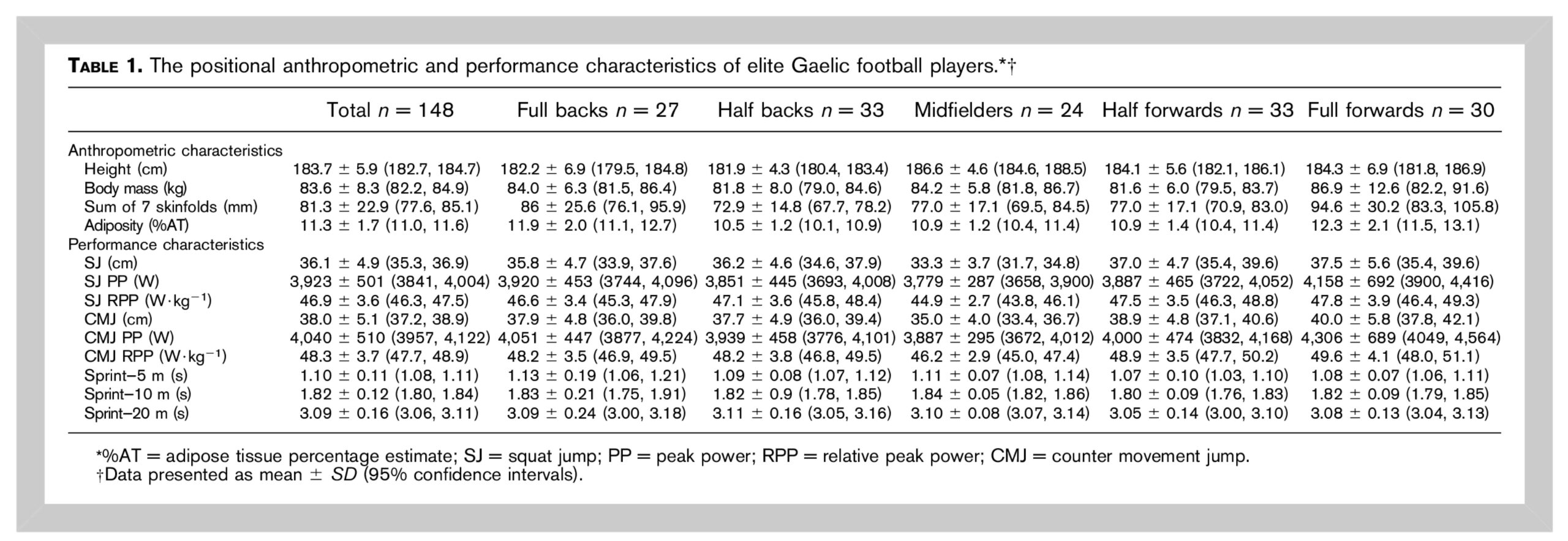

Physical Qualities of a Gaelic Footballer

Anthropometry

Anthropometric data of Gaelic games have been extensively researched throughout the years. Unsurprisingly, Gaelic footballers (178 ± 22.1 – 187 ± 7 cm) have found to be smaller in height than rugby players (182 ± 6 – 190 ± 10 cm), larger than soccer players (177 ± 6 – 179 ± 5 cm) and similar in size to Australian footballers (180 ± 6 – 188 ± 6 cm) (Beasley, 2015; Strudwick, Reilly and Doran, 2002; Reeves and Collins, 2003; Johnston et al., 2018; Brazier et al., 2018). Recent studies by Shovlin et al. (2018) and Boyle et al. (2021) examined the variation in performance and anthropometric characteristics (Table 1; Figure 2 and PDF) of elite Gaelic footballers competing in the AIFC. The mean height of all participants was 183.7 ± 5.9 cm, while the mean body mass was reported as 83.6 ± 8.3 kg, the sum of seven skinfolds was reported to be 81.3 ± 22.9 mm corresponding to 11.3 ± 1.7 % body fat. Taking position into account, midfield had the tallest players (186.6 ± 4.6 cm) while the half back position accounted for the smallest (181.9 ± 4.3 cm) players. This difference in height may be related to the tactical preference of the coaches, with taller players residing in more central positions to contest aerial possessions (Kelly and Collins, 2018). Similarly, the leanest players resided in central positions (half backs, midfielders and half forwards), possibly due to the distance covered within a game (Beasley, 2015). The anthropometric differences between elite and sub elite players has also been investigated. Elite intercounty players were taller (181 ± 4 vs 175 ± 6.4 cm), weighed more (82.6 ± 4.8 vs 76.5 ± 6.7 kg) and had less body fat (11.3 ± 1 vs 18.3 ± 3 %BF) than their club counterparts (Beasley, 2015; Reeves and Collins, 2003). The increased muscle mass and reduced body fat levels are necessary physical traits associated with the higher standards of performance (Beasley, 2015).

Figure 2: Anthropometric and performance profile of elite Gaelic football players comparing position and role (Boyle et al., 2021).

Table 1: Positional anthropometrics and performance profiles of elite Gaelic footballers adapted from (Shovlin et al., 2018).

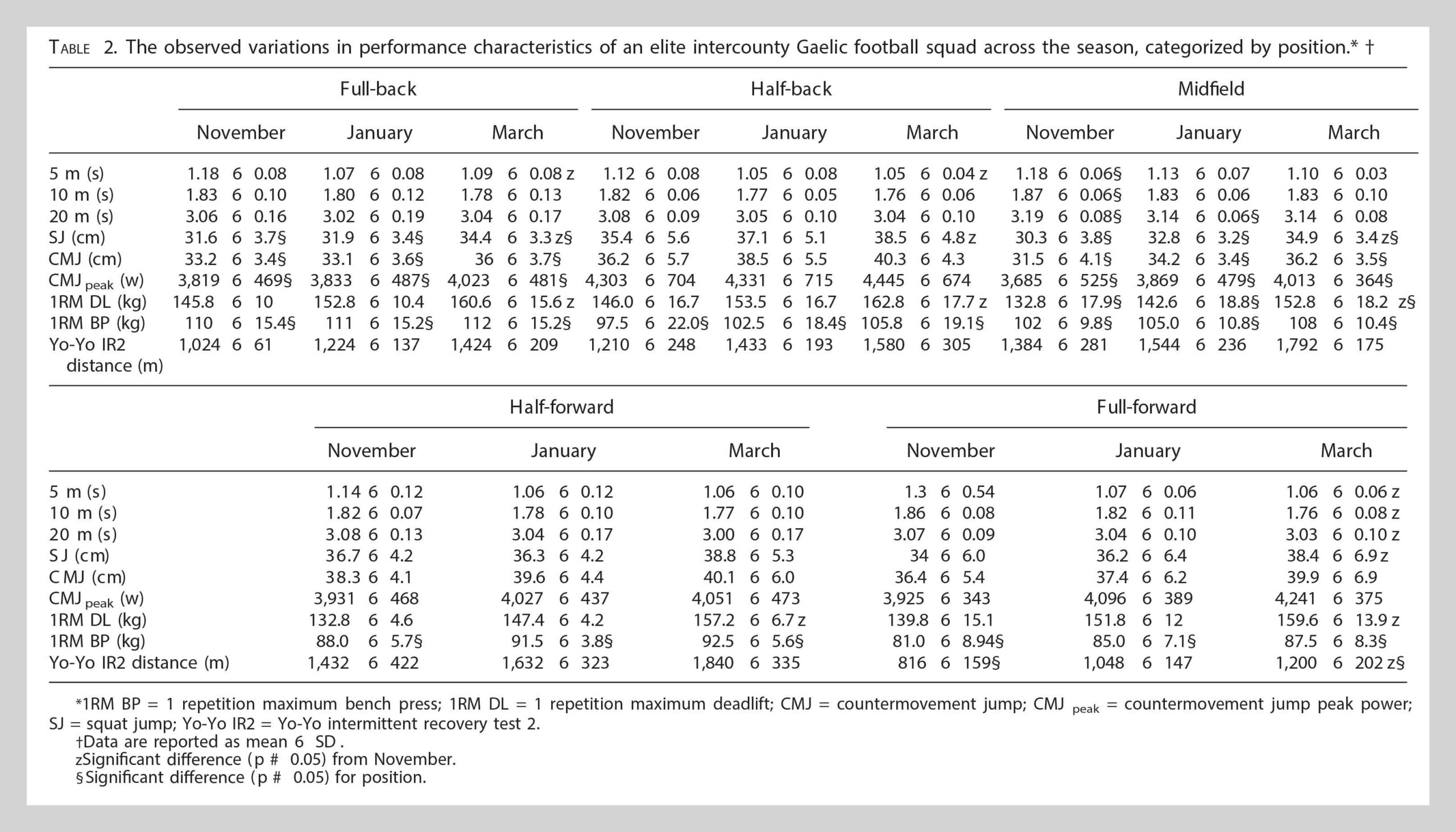

Body fat levels are of particular importance when it comes to the acceleration capabilities and aerobic capacity of Gaelic footballers as a high percentage of body fat (%BF) may have a negative influence on both these measures (Brown and Waller, 2014; Reilly and Keane, 2002), where body mass must act against gravity such as running and jumping (Doran, Donnelly and Reilly, 2003; Reilly and Collins, 2008). Additionally, a higher body fat level and a higher body mass have been shown to have a negative impact on aerobic capacity (Maciejczyk et al., 2014), however, a high body fat level and not high body mass, has been associated with negative anaerobic performance (Maciejczyk et al., 2015). This influence of body fat percentage and high intensity performance can be observed the Yo-Yo IR2 test. Kelly and Collins (2018), found that full-forwards , who carry the greatest level of body fat, covered the least distance during the intermittent test compared to all other outfield positions across the season (Full-forward: 816 ± 159 – 1200 ± 202 m; Other positions: 1024 ± 61 – 1840 ± 335 m). As previously discussed Shovlin et al. (2018) found that full forwards had higher levels of body fat (12.3 ± 2.1 %BF) compared to the rest of the positions. Additionally, half backs (10.5 ± 1.2 %BF) and midfielders (10.9 ± 1.2 %BF) had the lowest body fat levels of all playing positions (Shovlin et al., 2018). The higher body fat of full forward and lower body fat of half backs and midfielders may be attributed to the differences in the total and high-speed distances covered during match play with the full forwards covering less total and high speed distance (Total: 6544 – 7290 m; High Speed: 1066 – 1666 m) than the central positions (Total: 8200 – 9744 m; High Speed: 1584 – 2422 m) during match play (Malone, Solan and Collins, 2017), resulting in a lower energy cost of match play and thus lower energy expenditure (Malone et al., 2017a).

In addition, literature has found that the body fat levels of elite footballers has ranged from 11-18 %BF between the different positions with reductions in body fat levels occurring throughout the course of the season (Davies et al., 2016; Kelly and Collins, 2018; Shovlin et al., 2018). These reductions in body fat may be as a result of additional training and match demands may result in a greater energy expenditure during this period of the season and thus a greater reduction is observed (Kelly and Collins, 2018). As reductions in body fat occur in unison with positive speed, strength, power and energy system adaptations (Kelly and Collins, 2018; Shovlin et al., 2018), it then therefore may be advantageous for all Gaelic footballers, especially for full forwards, to maintain lower body fat levels, as lower body fat levels are associated with better physical performance (Kelly and Collins, 2018; Shovlin et al., 2018). However, during the off-season, these higher body fat levels may be important to drive positive adaptation in hypertrophy and strength as an increased body fat is a function of a calorie surplus (Slater et al., 2019). This calorie surplus, when coupled with resistance training, results in favourable adaptations in fat free mass (Slater et al., 2019; Leaf and Antonio, 2017).

Table 2: Seasonal variations in anthropometrics and performance profiles of elite Gaelic footballers adapted from (Kelly and Collins, 2018).

Strength

Although research is limited on this topic, maximal strength and power are contextually important to Gaelic football match play during kicking and tackling actions (Reilly and Collins, 2008). Previous research has recommended that upper and lower body strength, power and trunk conditioning should be …

Responses