How to Deal With Unpredictable Clients/Athletes (The Agile Way)

I am sure that most of you encountered the following (frustrating) situation – you do your best to create custom workout for your client/athlete, and then they bail on you, skip the trainings or do the workouts in the order that suits them best (in their own opinion).

So, one of the biggest questions is: If a client/athlete skips a certain workout/workouts, what type of training should they perform the next time? Should you just continue with the program, as if they did not skip a workout(s), or start from the beginning?! The answer to this, and other related questions, as well as more useful suggestions and strategies, are the issues I have put my focus on in this article.

There are multiple uses of Agile Periodization when working with personal clients. I’ll share two archetypal situations.

Building a perfect program

Imagine you have a friend who wants to start going to the gym. He have enlisted a lot of objectives (or qualities) he wants to develop: “I want to reduce the waist size, get bigger pecs and biceps, feel better, have a better sex life and look better naked”. Your normal reaction, since you are the type of a coach who wants to give 100% effort in planning and delivery, would be to make custom-tailored individualized workout, specially designed for this individual and his objectives. You end up spending 4 hours writing such a program and sending it to your friend. Two months later, you ask him how it is going and he responds with “Sorry mate, I didn’t have time to go to the gym. Program looks great, but I haven’t done a single workout”

This happened to me multiple times. Until I got smarter. There are multiple mistakes that are done here. First one is that we assumed that the client has set correct goals/objectives. Sometimes this is not the case. Our goal will be to minimize the complexity of those goals and focus on what is ‘controllable’ (i.e. ‘process’ goals – how many times he needs to hit the gym, etc.). Our client might enlist numerous goals, but we might look for a ‘common factor’ behind all those goals – or, in other words, make things less complex.

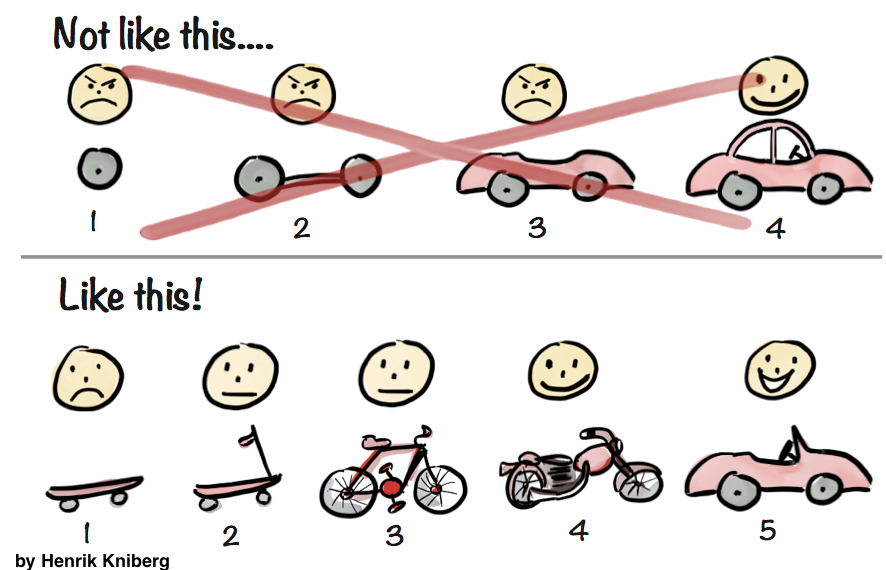

Second error that was made is pre-planning too much. We do not know if this client of ours has any experience in the gym and if he knows how to perform certain exercises. We also do not know how he will respond to training exercise selection, frequency, volume and so forth. Besides, we wasted huge amount of time and energy to write down a perfect program that was not even performed. Enter ‘good enough’. The goal would be to start with ‘satisficing’ – the program that is ‘good enough’ and represents MVP (Minimum Viable Program).

Figure 1. Minimum Viable Product

This MVP program is very simplistic, and yet great for ‘probing’ the client and getting him pretty good results, without you losing time for writing the perfect one. This is very similar to IT startups launching MVP (minimum viable product) as soon as possible and feeling the market, while minimizing risk for wasting money to develop something perfect that no one will use or buy.

You can also make your client jump few hoops before you attempt to give him custom made program. I am aware that some clients demand special treatment and guided training, but the principles of MVP and Agile program design hold true for them as well. However, when it comes to writing a program to a friend, or someone else you are not actually coaching, starting with MVP and making him jump few hoops to judge his motivation, could be a good risk-safe(er) strategy, than wasting time on building a program one might not perform at all.

Make sure that clients can perform the basic movement patterns (push, pull, squat, hinge, carry, core) before you start designing and using some crazy exercises. Start with the basics.

Haphazard attendance

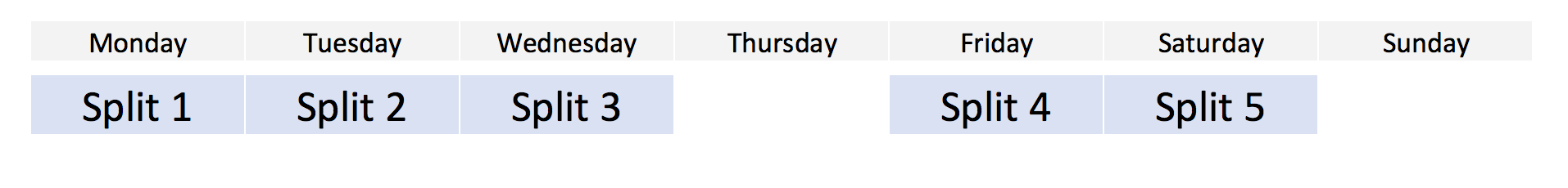

Continuing the example above – imagine you design a split training system (or multiple different workouts):

Figure 2. Split training system

Now imagine the athlete doesn’t show up on Wednesday. What is the course of action afterwards? Will you do Split 4 (or Workout 4) on Friday, or do Split 3? What if this happens quite often?

In data analysis, we have an approach to deal with ‘missing values’. One of the first things one might need to do, is to figure out if missing values have some pattern, or they are just random. There are multiple ways to evaluate that hypothesis, but in our case we can check the dates of missed workouts, or the workouts proceeding or following the missing workout. We might have a client that keeps missing Wednesday workouts, he might be missing leg workout (because he dislikes them), or missing workouts after a Split 2 (Workout 2) which might be due to the fatigue and soreness the next day. You definitely do not need to do Randomized Control Study to do this with confidence, but rather putting a more thought into it might be sufficient.

Be it completely random, or your client skip workouts with an agenda involved, there are few strategies to deal with this.

Strategy 1: Do not have the split system

The easiest solution would be to have a very simplistic program structure. This is mostly a variation of the full body workout in which all major qualities are being hit (or major muscle groups). From a risk and uncertainty perspective, you diversify your training volume/load to multiple qualities on multiple days, so if one misses a few workouts, no major damage will be done. On the other hand, if you perform leg work on a single day, and if that workout is missed, it will take a lot of time until those qualities are being developed again, as shown in the image below.

Responses