Applying Agile and Robust Planning Strategies to Speed Development in Team and Field Sports

Speed Is King

Team and field sports are punctuated by high-intensity efforts—the moments that matter most happen at top speed. Whether it be chasing a through ball in football before a goal being scored (Faude et al., 2012), a length of the field try in rugby, or a stolen base in baseball, speed affords athletes the opportunity to break open the game. Speed also clouds coaches’ and administrators’ perceptions of an athlete’s worth—faster athletes earn more money (Treme and Allen, 2009)—regardless of whether or not this is necessarily associated with performance. Whether it’s in creating a team of athletes better prepared to take advantage of their perceptual-motor landscape or in helping a private client get paid, strength and conditioning coaches should be highly concerned with speed development.

As previously discussed on Complementary Training, the agile periodization approach aims to address uncertainty in training by implementing robust training planning strategies. Traditional undulating or block periodization models tend to overly rely on an industrial age mechanistic understanding of physiological training responses. For example, Kiely (2012) argues most periodization theory is based on the work of Taylor (1919) concerned with management strategies for factories and production lines to formalize systems of efficiency following the industrial revolution. This model purports that outcome A must be achieved prior to outcome B, outcome B before outcome C, and so forth, much like the process required for Henry Ford’s Model T to roll off the production line. In training, this is akin to block periodization’s assertion that for any realization of training to occur, first an accumulation and transmutation (scientism vs. scientific—just because something sounds scientific, doesn’t make it so) phase must be completed (Issurin, 2008).

However, we now appreciate that physiology, biomechanics, sports psychology, and motor learning and skills acquisition all form part of a complex, dynamic system—where no single change can be made in isolation without countless unknown cascading butterfly effects that influence performance. Training cannot target a single system or quality in isolation. There is no such thing as ‘maximal strength’, ‘anaerobic power’, or ‘maximum velocity speed’. These are just models or concepts that we use to help us simplify and understand reality. That’s not to say we can’t or shouldn’t use models, however, we must understand and appreciate their limitations when building training programs that target vague or theoretical components of performance.

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Problems Faced by Strength and Conditioning Coaches Delivering Speed Programs

Contemporary physical preparation leans heavily on the experiences of track and field coaches to inform speed development programming. Personally, I have used resources like Altis, followed coaches online like Mike Young, and shadowed six-time New South Wales athletics coach of the year, Roger Fabri, to learn the science and practical application of linear speed development. This is where I learned about different drills, elements of technique, how fatigue can affect training and the prescription of sprint training. However, I continue to wonder how well straight-line speed, in a sterile environment, transfers to the chaos of sports.

I’m not the first coach to search for improved transfer in speed training. Many have followed a similar journey. Unfortunately, for too many coaches this leads to the fads and gimmicks of eyewash agility ladder footwork patterns, knee bungees, and cone drills. None of these adequately replicate the dynamics of movement to overload training in such a way that creates positive training adaptations (Weyand et al., 2000). In my experience, most athletes would still be better off working on straight-line speed with a track coach.

Video 1 – Eyewash training video

Sprint training volume is a controversial topic. Even among track and field coaches, there is much disagreement regarding how much sprint work is appropriate. Haugen et al. (2019) note that the general best practice for acceleration training is 100 – 300 m per session and for maximal velocity sprint sessions is 50 – 150 m top speed volume. It is worth considering that these recommendations are for sprint specialists. These athletes don’t also need to worry about skills and conditioning. Thus, it’s safe to assume our team and field sport athletes are better suited to working at the lower end of these spectrums.

However, elite sprinters have a long history of technique development, operate at much higher maximal outputs, and have extensive sprint focussed training histories. Does this mean our field sport athletes need more work to get them up to speed (da dum – see what I did there…)? Further, what are the sprint-related demands of their specific sport/position? The training must prepare the athlete for worst-case scenarios—train hard, play easy. With this being the case, perhaps our field sport athletes should train at the upper end of the Haugen et al. (2019) sprint training volume parameters.

To further complicate the sprint training program, if you’re like me you’ve got 15 minutes to get the athletes warmed up, complete the sprint training program, and provide enough time for a quick drink before handing over to skills. So how do we jam so much in with so little time? And what if so and so the athlete is always too sore on game day +2 for high-speed running? You need a robust planning strategy. Remember, you’ll always hit acceleration when you hit max velocity – but not always the other way around—how can this form part of your planning strategy?

Components of Effective Speed Programming

In a recent Twitter ‘ask me anything’, Altis CEO and sprints coach Stuart McMillan discussed his ‘know, think, guess (KTG) model’ for decision making in training planning. McMillan frames his training philosophy around what he knows to be true, what he thinks to be true, and finally what he guesses to be true. In much the same way agile periodization relies on the barbell strategy (Jovanović, 2019, Taleb, 2007), McMillan doubles down on robust components of training—what he knows to be true makes up ~75% of the program. He also makes a small but consequential investment in the upside, what he thinks to be true is 20% and the final 5% of his training are guesses, experimentation, and novelty for novelty’s sake.

So, with respect to straight-line speed and training for sprint performance in team and field sports, what do we know to be true?

- Regular sprinting is required to condition for top speed (Oakley et al., 2018, Edouard et al., 2019, Malone et al., 2017)

- Longer recoveries improve training outputs (Haugen et al., 2019)

- Strength and power training supports speed development in less trained athletes (McBride et al., 2009)

- Faster sprinters have a higher proportion of fat-free mass (Barbieri et al., 2017)

- Muscle actions and kinetic sequencing is specific to movement velocity with phase transitions occurring from acceleration to top speed (Higashihara et al., 2018)

- Resisted sprints improve acceleration in less trained athletes (Cross et al., 2017, Cross et al., 2018, Morin et al., 2017)

- Large and abrupt changes in sprint volume increase the risk of injury (Carey et al., 2017)

- Sprints approaching top speed are relatively uncommon in field sports but are often associated with scoring situations (Gabbett, 2012, Faude et al., 2012)

- Plyometrics and horizontally orientated jumps improve sprint performance in less trained athletes (de Villarreal et al., 2012)

- Higher level sprinters demonstrate greater levels of stiffness (Haugen et al., 2019)

- During acceleration, higher level performers better orientate their ground reaction forces in the global horizontal vector (Morin et al., 2011)

- Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground reaction forces, not more rapid leg movements (Weyand et al., 2000)

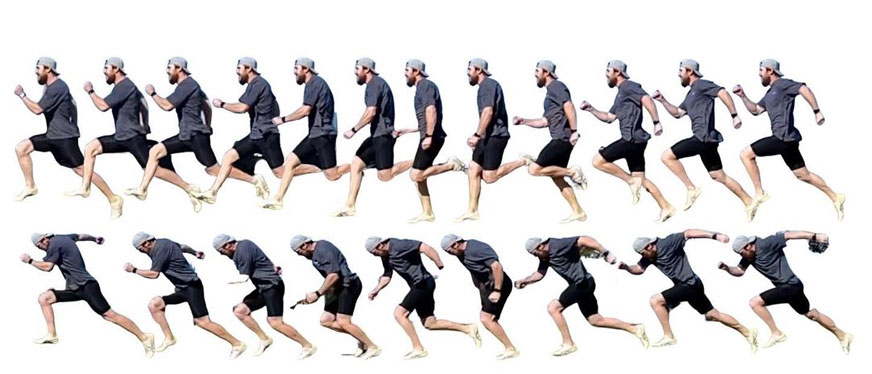

Figure 1: Top speed and acceleration gait patterns are different. During upright sprinting (top), the swing leg lever is shortened during the recovery phase whereas, in acceleration (bottom), the foot recovers low to the ground—these differences result in contrasting mechanical forces applied at the hamstrings during the late swing phase. Therefore it is important to expose athletes to these specific stimuli for both development of performance and to mitigate injury risk

Knowledge of these factors should form the basis for 75% of our speed development program. Therefore, if working with younger, less developed athletes, we should dedicate more time, energy, and effort to supplemental general training in the weights room. Additionally, our speed sessions need to be completed regularly—at least once per week—and should use long recoveries. We should also train both acceleration and top speed. And our exercises, drills, and coaching cues should help athletes develop the ability to achieve orientate and deliver ground reaction forces in the most efficient and effective way possible. It will also be beneficial to layer game-like scenarios over speed development to allow for exploration of the perceptual-motor landscape, variation of fluctuations, and challenging/stabilization of attractors.

Think to be true is where personal opinions will differ, so for the purposes of this exercise, these are simply my own personal beliefs regarding training for speed development:

Responses