Coordination Training

Coordination training is an often misunderstood and at times haphazardly delivered element of physical preparation. As with everything in coaching, context is king. A simple search of coordination training can lead you to a whole host of elaborate and dynamic drills. A well-meaning coach sees these drills and looks to implement them in their next practice – again I’m not suggesting that this is malpractice, but, more often than not, the context for including that exercise is often missing.

I have been taught by my mentor Darren Roberts, that at any one time, someone should be able to step into your session and ask you the question “why are you doing that exercise and what are you looking for?”, you should be able to answer this three times. Let’s take the above situation as an example, the coach has found ‘an amazing drill’ on social media, the post says it is working on reactions. So, when questioned for the first time on why they are doing said drill, they can comfortably answer why they are doing the drill “to develop reactions”, and maybe the second time the can confidently answer “tennis requires reactions”, but when probed deeper on “why is this important to this player and what are the key 3-5 coaching points you are looking for?” – this is where the coach starts to come unstuck, because as good as an exercises may look, if you do not know extensively the why and how to correct technique to achieve excellent execution, then it is just a random drill, lacking in specific context.

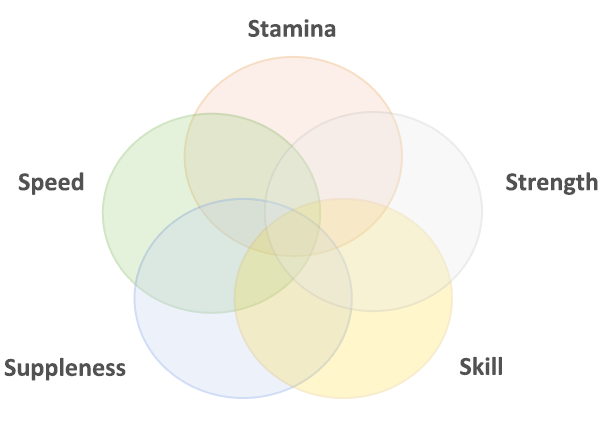

So where does coordination training sit in the physical preparation of tennis athletes? If we look at the key bio-motor abilities of an athlete, we can use the categorisation of the 5 S’s (where Coordination would fall within the category of skill):

- Strength

- Speed

- Stamina

- Suppleness

- Skill

As we can see from the diagram above, no one element stands alone, they are all interconnected, for example:

- Strength-Speed

- Speed-Strength

- Strength-Stamina/Strength-Endurance

As a tennis-specific S&C coach there needs to be a balance in the development of skill. Tennis is a sport that demands highly skilled athletes, in order to aid this skill enhancement as a coach you are constantly teaching both competency and capacity. Competency relates to the execution of a task, be it in the gym coordinating the execution of a weightlifting derivative or refining a technical issue in the serve, both of which require high levels of coordination. Capacity relates to the ability to repeat that task under speed, fatigue, complexity and pressure, which again demands the athlete to be well-coordinated. Therefore, to enhance on-court performance I am constantly trying to find a balance between general athletic development tasks and sport-relevant tasks, such as on-court movement with a medicine ball. As you can see below, similar shapes can be seen both in general off-court physical development task and that of highly specific sports movement.

When defining coordination, I like to use John Kiely’s quote – “Coordination is when the central nervous system organises the body, to satisfactorily solve a movement problem, for the least uptake of resources”. My interpretation of this definition is that the athlete needs to most effectively and efficiently, create an answer to a movement puzzle set by the environment or the opponent. Take, for example, the movement to a wide forehand, a supposedly simple task. However if we consider that a player may have to solve this ‘puzzle’ on different court surfaces – indoor and outdoor hard/carpet/clay/grass – in each situation the solution may be slightly different, before even taking into consideration the type of shot the opponent has sent. This represents a combination of the coordination components of adaptability and differentiation.

When identifying the different components of coordination, in order to help me remember I use the mnemonic RB RADIO. Below I will outline the components and give a simple example of each:

- Rhythm – best thought of as the ability to execute tasks using different tempos and speeds. Think of the different speed and tempo of movement to the net under two separate situations – chasing down a tough drop shot versus movement towards the net after an effective shot, putting the opponent under pressure and receiving a short ball.

- Balance – possibly the most important factor in tennis, this quality underpins movement, it is the management of equilibrium in both static and dynamic situations. Think how wide the top players can be stretched off the court, yet can maintain dynamic balance, to not only get themselves out of trouble, but hurt their opponent.

- Reaction – reducing the time between reading the most relevant stimulus and creating action. Visualise a great returner reading a subtle indication in the opponents serve mechanics to give you information on where to return from.

- Adaptability – arguably a combination of most of the qualities, to deliver the best possible answer to a movement problem/situation. As mentioned earlier, tennis is one of a few sports where players must adapt to several different surfaces.

- Differentiation – the action or process of distinguishing between two or more elements. The ability of a tennis player to rotate and differentiate the shoulders and hips is a high order principle of agility.

- Interoperability – the linking together of different elements. In tennis-specific movement combining the skills of a split-step, crossover and side-steps to move to a shot.

- Orientation – understanding your relative position in relation to your surroundings. For example, the ability to execute a drop shot, before having to transition to a smash and having to orientate yourself in the air to hit the shot, land, and move to your next position on the court.

Now, where does coordination training fit into the development of a tennis player? There is no getting around the fact that tennis is becoming an early specialisation sport – if we consider that Martina Hingis won her first junior slam at the age of 12, we must be creating high skilled players from an early age. The dangers of early sports specialisation are that athletes can become one-dimensional in their movement skills (this is a very interesting topic that would demand an article of its own), they can be left with a narrow bandwidth of movements. They can end up with overdeveloped sport-specific skills and underdeveloped global motor skills. Now in the case of tennis, I support the fact that in order to excel in that sport, early exposure is vital. However it is within our remit as coaches to also expose them to a much wider diversification of movement skills via developing motor skill proficiency.

Arguably the optimal time to focus on this type of training is with junior players. From a neural standpoint youth athletes’ brains are much more ‘plastic’ – meaning they are quicker to learn, develop and refine new tasks. But, this training is not exclusive to these ages; even at the age of 25 we can still be refining our walking gait, so this type of training can still be highly beneficial for players of all ages. I use coordination tasks with all my athletes, integrating them into warm-ups, movement sessions and rest periods in the gym or on court drills.

Here is pre-hit warm up with Roger Federer in action with his physical trainer of 20 years. In my opinion Roger is the most coordinated athlete in history. In the space of eight-and-a-half minutes you will see an example of the whole spectrum of coordination qualities.

Childhood is a time of accelerated cognitive development; particularly the sensorimotor cortex, which is a key factor for developing fundamental movement skills (FMS) and neuromuscular coordination. So, to ensure the biggest positive transfer of training we must ensure this work is prioritised early and continued throughout childhood into adolescence.

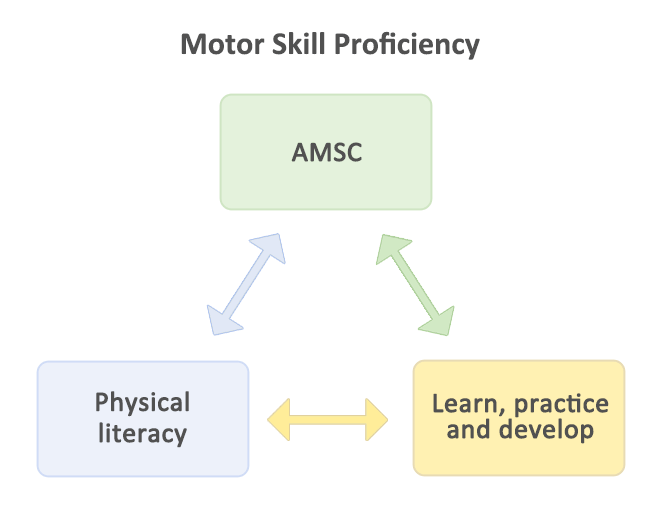

First it is important to define the components of effective motor skill proficiency.

FMS can be broken into three key areas:

- Locomotion – running, hopping, skipping, jumping, landing

- Stabilisation – bracing, balancing, anti-rotation/extension/flexion/lateral flexion

- Manipulation – throwing, catching, grasping, striking, kicking

In addition to FMS, the athlete must also be able to produce, reduce and absorb force. These are expressed by the following movements:

- Lower body squatting

- Lower body hinging

- Upper body pushing – vertically and horizontally

- Upper body pulling – vertically and horizontally

- All the above bilaterally and unilaterally

The combination of the two elements has been classed by Lloyd and Oliver as Athletic Motor Skill Competencies (AMSC). The exposure to and the development of these AMSCs prepares the athlete for more advanced training methodologies such as weightlifting, high intensity plyometrics and sport-specific speed and agility.

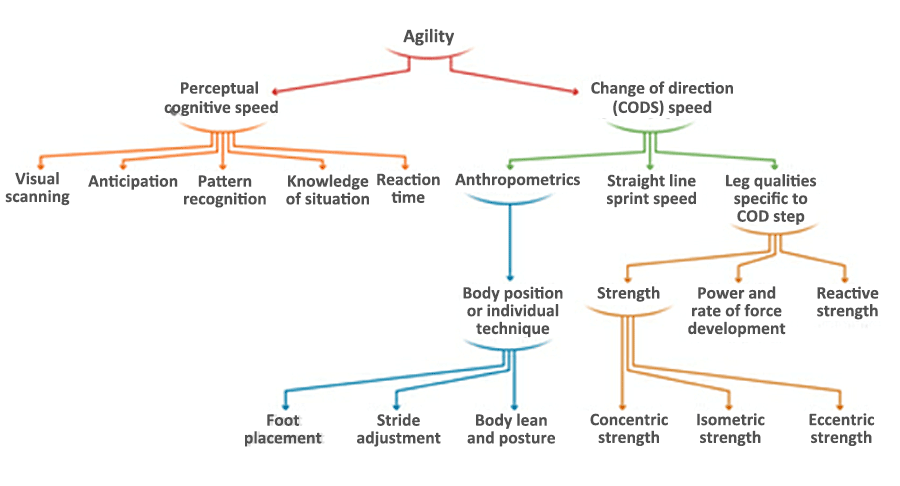

In addition to the physical components, perceptual-cognitive development should also be prioritised. This can be achieved by including elements of coordination within movement tasks, working on reactions, anticipation, visual scanning, pattern recognition and knowledge of situations. These elements are those suggested by Young and Farrow as integral components of agility. It is the combination of these elements with change of direction speed which underpin the movement demands of a tennis player.

In conclusion, to create effective motor skill proficiency with the integration of coordination training, there are there five key components:

- Cognitive processing – the task must force the athlete to think via solving ‘movement puzzles’

- Execution of the correct fundamental patterns – know your coaching points. What does good look like?

- Expressing muscular force – the sport of tennis, even from a young age, demands effective force production, reduction and absorption.

- Enriching learning environment to maximise motor skill proficiency – make it fun.

- Systematic – via context specific planning and delivery, you have the potential to overcome genetic limitations and increase the ceiling of expected motor skill development.

By following these guidelines, movement skill development can be specific to the individual, which can include progressions and regressions. This also allows athletes to revisit key FMS and coordination skills during growth and adolescent awkwardness. This holistic approach to development produces more robust and adaptable athletes, which may, in turn, lead to reduction of injury risk and overuse injuries, while at the same time having a positive impact on performance.

Our job is to extensively master the basics, in order to create the most effective and efficient athlete, who is able to adapt, regardless of the situation or environment.

Here are some examples of putting these guidelines into effect:

Responses