Interview With Me by Steve Olson

This is reprint of the interview done by Steve Olson for Science of Sports Performance.

SO: Mladen, how did you enter sports performance training, and what specifically got you so interested in periodization and program design

MJ: I think I somehow “stumbled” on it. I came from the “nerd” background (although I have always been “athletic” but never pursued anything serious) with programming skills, but somehow entered Faculty of Sports and Physical Education, even though I always wanted to be engineer. One of my first contacts with performance training was though martial arts and interests in martial arts. Back then there were not many great books on the performance training topic (at least not translated to Serbian/Croatian) and most of my interests came from reading stuff on yoga, martial arts and alternative medicine (I laugh at it now though). What REALLY got me into things was reading Supertraining book by late Mel Siff (I’ve read a suggestion in Low Back Disorders by Stuart McGill). I started questioning everything I knew, and although the book is not very practical, reading it early in my career “planted” critical thinking that was useful down the road. That, and making others pissed off on forums and news groups (yes, I was that kid who quoted Siff in every sentence J). I final years we were lucky to enter internship program with Partizan Basketball Club and then I started really working in practice more and more.

SO: Who have been your biggest influences up until this point in training?

MJ: Hard to name, but besides Mel Siff, it was late Charlie Francis. His forum and DVDs were eye opening and great way to network and learn more about other great resources. Mike Boyle was influential on me as well, along with Dan Baker who always answered my annoying questions on email. Joe Kenn, Kelly Baggett, Lee Taft and numerous other coaches and experts. Now it is much harder to filter good information since everyone have blogs and 500$ DVD collections with training secrets.

SO: Why did you found Complementary Training, and how has it evolved since its inception?

MJ: I started writing for various sites and forums, like EliteFTS long before I started up my blog. I wanted to post some of my thoughts without torturing any other website and waiting for the articles to be posted. So I started the blog, right after I finished with the internship at Mike Boyle in Boston 2010. The name “complementary” came from my personal quest to reconcile certain paradoxes, not only in training but in life in general (i.e. philosophy, physics, and so forth). First time I stumbled on the term was in awesome and must read book on skill development by Keith Davids and coauthors “Dynamics of Skill Acquisition” who pointed to work by Scott Kelso and David Engstrom (e.g. “Complementary Nature”). This was a real bliss for me since acquiring this “complementary” approach helped me to solve some complex dichotomies down the road.

SO: You have talked to strength coaches all around the world, what general philosophy differences do you see in American coaches vs the rest of the world?

MJ: I still don’t have enough of experience nor knowledge to answer this question. With the invention of internet and general globalization I think that the approaches are starting to “level up” although there still seems to be some differences. One of the differences might be the culture and a good introduction to these issues is “The Culture Map” book by Erin Meyer. The issues with comparing group to another group is that people often forget about the spread and overlap – and they think that EVERYONE in one group is different that EVERYONE in another, and this is never the case. I think that groups differ on different scales when it comes to training, but one of them might be the emphasis on motor abilities (potential) versus skill (economy, efficiency of movement). This might be seen in powerlifting (e.g. Westside vs Sheiko) and in team sports (e.g. emphasis on motor abilities cycles and generally making athletes stronger in the gym versus making athletes and team more skillful; see Tactical Periodization) for example.

SO: What do you think most people in the industry are doing right, and where can we improve most?

MJ: I think the great thing is that we are starting to question more and more dogmatic approaches to training and dogmatic sources of information. The bad thing is the confusion and information overload that follows (and making everything “relative” and “it depends” and that can be paralyzing). But I think this is pretty much the old problem of Socrates vs. Sophists – absolute vs. relative Truth and this is common in every domain. And here again we can see the power of “complementary” approach that acknowledges that these are not either/or dichotomies but complementary aspects. We cannot discard the “old ways”, but we must take into account the novel findings and technology without reinventing the wheel. Similar to Bayesian inference where we take a priori knowledge together with the new evidence to estimate a posteriori proof.

SO: You recently brought up a long discussion on facebook regarding reliability and validity of HRV. Did that affect your viewpoint on the topic, as well as playing with your own iThlete HRV monitor?

MJ: I have been only slightly experimenting with those tools – because the culture of the teams I used to work with didn’t allow for the robust implementation. I think there might be something to it, but we need to take it together with other data and context to yield insightful and actionable feedback. Some of the vendors are open with sharing the algorithms and reliability issues, some use “black box” approach. In any case, it is up to the user to do his own “reliability” study with his own athletes and within his own context. The goal of such an analysis is to give us signal vs. noise estimates – for example we need to know the normal biological/measurement variability when there is no “real” change and then we use this to estimate our certainty in real effects across time. Imagine one have a scale that varies for 1kg (SD = 1kg, hence 95% of spread is ±2kg) every time you step on it. Then after a week of dieting you see 3kg loss. How certain are you if this is “real” effect and not a measurement fluke? With some metrics there is a big biological variation and we need to make sure we are taking that into account when we estimate the effects.

We are all looking for cutting edge in technology, and team are basically “bragging” who is taking more data – but at the end of the day it is about making better training decisions and getting better results not fancy charts for the weekly reports. Unfortunately, our ability to use the data is not growing at the same speed as the amount of data.

SO: One topic you have discussed is intervention before monitoring. I love this concept: if you aren’t training hard or properly, what do you have to monitor? Can you expand upon this idea?

MJ: The concept came from my “mental exercise” on where I would spend a budget money (see HERE). One of the “rules” I came up with was to spend money on intervention tools before spending on monitoring tools. I would like to be able to intervene and/or cause effects before I could measure them. For example, buying force plate to estimate isometric pull strength before having a decent gym is unnecessary. Monitoring sleep without the ability to intervene, get the quiet, cool and dark room is also useless.

SO: When people talk about “Sports Specific” training, what does that mean to you? How does training rugby vs soccer significantly influence the various aspects of your yearly program?

MJ: I will again use the philosophy of Complementary: we need to know what type of loads and stress athletes are experiencing in their practices and games, then try to find a way to “complement” those sessions with the goal of removing the “limiters” and wrap that into the sport and local culture (“they way of doing things here”). By removing “limiters” I refer to improving performance/production (or actually “potential” for performance on the field) and capacities for performance/production over a long season/career (by avoiding too much load and causing too much fatigue, improving the “robustness” of players and so forth). In my opinion this is all there is – add culture, context and individual differences and you get applied training philosophy. We can call this “integrate” or “holistic” approach, but there is nothing fancy here.

When it comes to specificity it is kind of embedded in the above definition. Coaches tend to believe that their sports are special, but when it comes to physical side of things most if not all athletes need to run, accelerate, change direction, jump, bump, and so forth and repeat that over the duration of the game (but also over the training week). I have expanded a bit more on this HERE and recently Chris Gallagher wrote on the topic as well.

SO: What would a general yearly cycle for your soccer team look like?

MJ: What I am contemplating at this moment is to write down the new version of the “manual” I wrote couple of years back (click HERE)

I have been reading recently on the Lean production system (e.g. Toyota) and Agile practices in software/project development and I think they have a lot to offer to training planning. I guess a lot of coaches are already using them without knowing. They are useful in managing uncertainty and delivering minimum viable product (MVP) using “iterative” and flexible approach that avoid over-planning (i.e. waterfall method). For me this means, using shorter cycles (e.g. 5/3/1, Verheiyen 1-2 weeks cycles in planning SSG for specific conditioning, Baker’s Wave Method and so forth) and complex approach where things don’t vary much (e.g. Tschiene periodization, Charlie Francis’ Vertical Integration). I just don’t buy the Bompa’s pre-planned cycles anymore, at least not in sports where pre-season lasts 4-8 weeks and competition lasts 3-6 months. And things need to integrated with something that’s called “Tactical Periodization” ( a fancy name for tactical training planning) which is also a “iterative” approach to planning. These things are still “boiling” in my head and I need to organize my thoughts in the near future.

SO: A topic I personally love and use in my program design is skill acquisition and motor control.

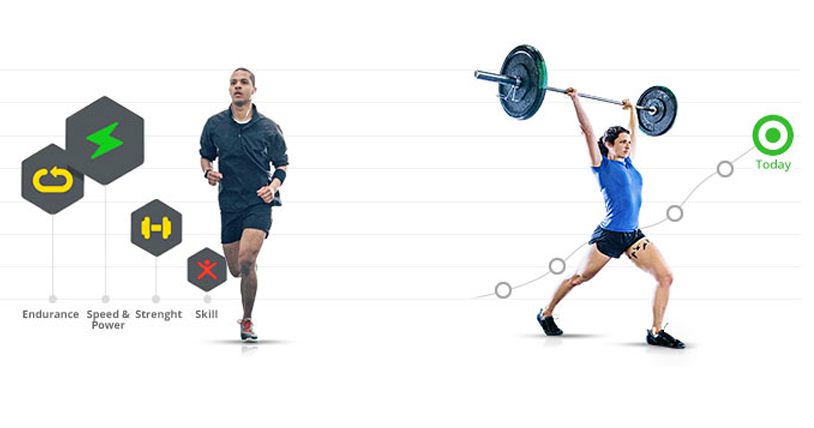

MJ: Yes – we tend to focus too much on “motor abilities” and disregard “skill” aspect, especially in “gross motor sports” such as powerlifting. For example, squat for non-strength athletes is a “way” of developing “strength” as motor ability and hopefully gain transfer to speed (another motor ability), while for powerlifter it is a “skill” or skilled movement with a lot of nuances. I like to portray this in my head as a “fractal” where you can zoom in indefinitely depending and keep finding “limiting factors”. The question is how deep down the rabbit hole one needs to go for a particular athlete and his needs. One thing I see coaches struggling with is they continue to use “classification buckets” for different athletes and sports and levels, without realizing that those “buckets” are just “mental economy” for easier functioning and need to be re-established for different levels/needs of the athletes. Here I am referring to classification to motor abilities (i.e. speed, strength…) and their sub-classifications (i.e. starting strength, strength-speed, speed-strength and so forth). We see this in “periodization” as well – we just keep using some “buckets” without questioning them and their implementation for our needs and then discuss/argue whether it is linear/non-linear, block, mixed and so forth. We should rather start with our mental model of “what is out there” (ontology), or our classification of things and see how is this affecting everything down the road.

One great book on skill training is mentioned book by Keith Davids.

SO: You have been writing about VBT and its practical application, what benefits have you seen while using velocity based training? Who do you implement it with, what equipment do you use, and how have the results of it affected your program design?

MJ: There are numerous benefits of VBT and the simplest one is higher effort by immediate feedback. This is useful in explosive sports, but I guess also in strength sports. Another benefit is using velocity to prescribe training instead of using 1RM (or at least use to make sure you are hitting what is being prescribed) since velocity seems to be more “robust” to day-to-day fluctuations in strength within-individual and different rates of improvement in strength between-individuals. It would take a lot to explain this in the interview, so the interested readers can find more about it HERE.

SO: What training protocol have you been interested in the most lately? Have you been able to implement it with your athletes programs?

MJ: One of the things that interests me lately is the emotional effects of training programs and the way the fit for a given individual. It is hard to experiment with this in team sports, but could be managed in individual and client based approaches. Greg Nuckols mentioned this in his Robert Pacey podcast and this article.

I think this is usually disregarded in planning especially because we tend to stick so much to 3×5 programs. Some people thrive on “stability” where they can see progress on same exercise(s) while some freak out and/or get bored/burned out by performing same stuff all the time and seek more (mental) variety. This individual characteristic needs to be taken into account when planning. The problem is that we don’t know this when we start mapping our “master plan” for next 6 months since uncertainty is highest in the plan beginnings and one way to manage this is to use “iterative” approaches I alluded above, such as Agile/Lean approaches from business and project management.

SO: A recent topic we have spoken at length about is DUP, or daily undulating periodization. This is a fascinating topic for me which I have had great success with, what are your thoughts on higher frequency training? Have you been able to implement the program with anyone?

MJ: If soccer players can practice soccer everyday, I don’t see why lifters cannot lift every day as well. But soccer players cannot play a game everyday, hence lifters cannot “grind” in the gym everyday (maybe Mike Zourdos can prove me wrong) for long. In my opinion high-frequency training is just one strategy one can use together with more “fatigue-based” approach (to use Mike Tuchscherer’s terminology) and probably should alternate between the two when things start to slow down or gets too boring. This might again come to the definition of “skill” and “ability” and the way this is affecting our planning, but also to individual preferences of the individual. Using DUP in this set-up might be more of an “emotional” thing and a way to manage fatigue than some special-biological-effect or reality. My body seems to prefer more frequent, medium/low volume, low “mental” strain (lower exertion or lower proximity to failure), more variable practices, than “balls to the wall”, medium-high volume, low frequency sessions (I tend to burn-out/get nagging injuries on those easily). That and over-prescribed progressions over weeks. That’s why I think VBT might be a interesting solution that gives you structured and goal-oriented workout, but still provide for plenty of wiggle room some people need.

SO: This question is about Fluid Periodization vs Set/Programmed Periodization for team sports. There is a few ways to adjust your training protocols, some coaches tend to have set goals, aka from January to February we are going to work GPP, max strength in march etc, whereas others adjust week to week depending on HRV, scheduling etc. How would you best interplay these two factors together to create the best program possible?

MJ: There is a GREAT free course (around 1h long) on the same issue people have in Project management (exactly why I believe we are re-inventing the wheel in S&C – there are plenty of solutions in other fields to the problems we are facing) . Using complementarity approach I think we need both (“waterfall” ~ “agile”). Some things are more or less “certain” and volatile, hence we need to use method that suits it. Emphasizing one over another is the problem. I believe, that generally we assume too much certainty in biological side of things and things tend to vary there. Recent interview with John Kiely is a gold mine for those interested in finding more in these issues.

SO: If you could recommend three books to all strength and performance coaches, what would they be? What three books have you read most recently that have impacted you the most?

MJ: I would recommend mentioned Keith Davids’ book “Dynamics of Skill Acquisition”, David Joyce’s “High-Performance Training for Sports” and Joel Jamieson “Ultimate MMA Conditioning”. HERE is one old list I wrote couple of years back.

I am currently reading new Vladimir Issurin book “Building the Modern Athlete” and it seems like a combination of his previous two books. One of the recent books that impacted me was “Antifragile” by Nassim Taleb, “Organized Mind” by Daniel Levitin and “Horizontal Jumps” by Nick Newman.

SO: This will be a lightning round! In two sentences or less, explain your general thought process as of today on the following topics:

- Barefoot training – Yes, if you have right surface and culture. In my opinion useful for warm-up

- Minimum adaptive threshold – Useful concept, but I guess “hard” to find in the real world. Demands some data analysis and modeling skills.

- Contrast / Complex Training –They have their use in my opinion, but some overuse those.

- Specialized exercises – Useful, as long as we are not trying to sell “sport specific” crap.

- FMS – marketing crap.

- Powerbreathers / crocodile breathing / Related – I am becoming interested in powerbreathers recently, since I believe there might be some easy to gain marginal gains that could be helpful with teams already training hard.

- Postural Restoration for athletes – A lot of coaches I respect embraced SOME of the ideas and exercises of PRI. There might be something useful there, but I think S&C coaches shouldn’t play PT roles too much I also think it is silly to blow up the balloon with the whole team – again depends on the cultures and “this is how we do things here” issues and ease of their change. The science of pain and function is still inconclusive if these “postural” issues are contributing to the cause or it is something else (e.g. brain). Some would tell this is similar to the difference in tire pressures in Honda Civic vs. Formula 1 (e.g. recreative athlete versus elite athlete), but we need to remember that PRI came from working with the former. Time will tell about usefulness of this method – I remain open, but critical and playing devil’s advocate.

Responses